This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

The institution of slavery in Brazil, over three centuries and to the present day, resulted in severe social exclusion and the cultural alienation of the black population. Despite centuries of suffering with no guarantee of basic rights, reparations policies have not been instituted.

After the abolition of slavery, Afro-Brazilians continued to be subjugated and systematically pushed to the margins of society, to fend for themselves. Legally, they could be imprisoned for vagrancy if they circulated without an employment card. Meanwhile, gaining formal employment was rare due to whitening policies, which included incentivizing immigration from Italy or Germany as cheap labor to live on the land and fill positions previously held by those who had been enslaved.

The whole framework of oppression, stretching over centuries, led to the emergence of abolitionist movements, and subsequently to the Black Movement. At first, the resistance movement demanded the bare minimum for people to survive. It also demanded reflection and remembrance of black culture—for years suppressed due to attacks and stigmatization, tools employed during slavery and to this day through structural racism in Brazil. And so, as a form of resistance, capoeira and samba circles appeared, essentially telling the oral and physical story of the culture and history of the African diaspora in Brazil. Criticized, persecuted, and criminalized by society, the survival of samba and capoeira is a classic manifestation of black cultural resistance.

Today’s Black Movement’s struggle is engaged in demanding and fighting for the basics, like representation in places of power and decision-making, equal pay and educational opportunities, and affirmative action. But none of these issues have a quick solution. Everything comes up against structural racism.

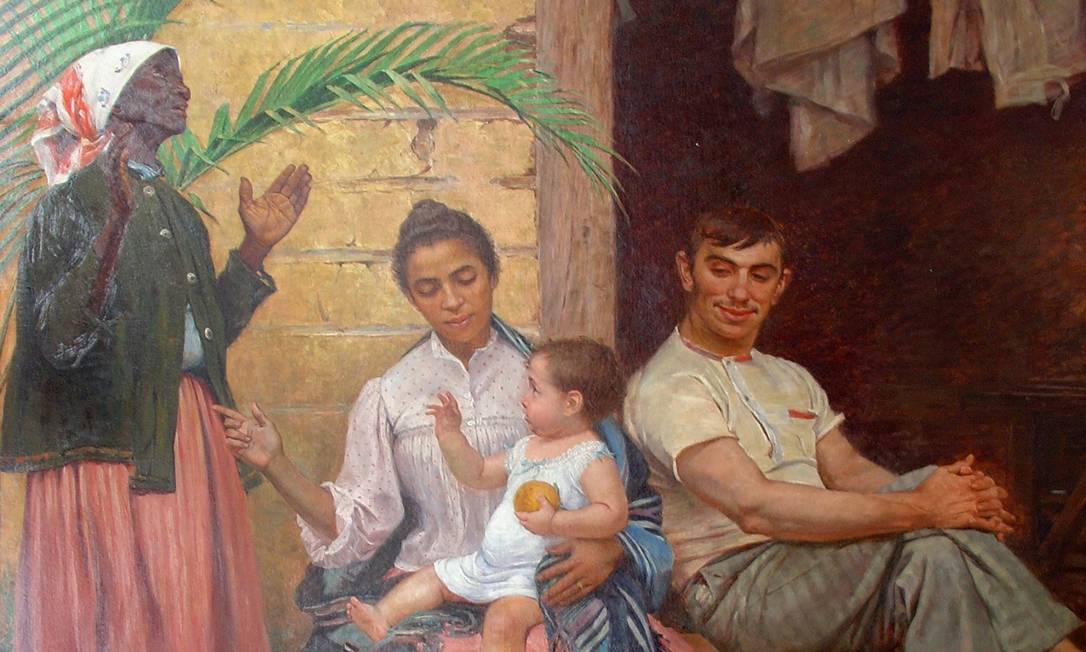

But what is structural racism? It is comprised of collective social practices which are very often unconscious or seen as politically neutral. Underlying everything that makes up our sociability in a society still marked by its slaveholding roots, continually affecting and shaping all of us, structural racism is historical, cultural, and institutional. The power system of structural racism chooses a color, a culture, and a religion to be considered the standard, thereby creating the “other,” the category of different, whose only distinctive feature is being non-white. Colorism can then be added to the equation as a colonial tool for enforcing hierarchy, regulating opportunities, and controlling miscegenation in Brazil. The advent of mass miscegenation granted different opportunities to individuals according to their phenotypical characteristics: lighter skin and straighter hair mean fewer social barriers that black (black and brown) bodies must confront and overcome.

This racist structure reproduces the typical social practices and the mentality of a slave-owning society, deep-rooted even today. As a result, black people see their opportunities for employment, income, education, survival, rights to housing and to a healthy environment, limited. Structural racism creates, maintains, and deepens disparities that develop between groups over time, the effect of centuries of oppression passing from generation to generation, including through language.

After centuries of naturalizing stigmas, of belittling and ridiculing black people, the use of racist words, phrases and jokes has come to be viewed as normal, natural. Some examples are the verbs “denegrir” (“to denigrate”), etymologically derived from the word “negro” (“black”), which means “to make more black, to turn dark, to darken, to stain the reputation of or to defame someone or something,” and “esclarecer” or “clarificar” (“to clarify”), derived from the word “claro” (“light”), meaning “to illuminate, to make lighter, to give out light, to understand, to become understandable, to distinguish, to make relevant, to become important, to explain, to give or receive correct information or clarifications, to inform, to make more instructive, to give explanations or foundations.” These words arise from the assumption that black or dark is something bad and that white or light is something good, something to aspire to. Therefore, whenever someone wants to undermine something or someone, they just point out its proximity to blackness.

After centuries of naturalizing stigmas, of belittling and ridiculing black people, the use of racist words, phrases and jokes has come to be viewed as normal, natural. Some examples are the verbs “denegrir” (“to denigrate”), etymologically derived from the word “negro” (“black”), which means “to make more black, to turn dark, to darken, to stain the reputation of or to defame someone or something,” and “esclarecer” or “clarificar” (“to clarify”), derived from the word “claro” (“light”), meaning “to illuminate, to make lighter, to give out light, to understand, to become understandable, to distinguish, to make relevant, to become important, to explain, to give or receive correct information or clarifications, to inform, to make more instructive, to give explanations or foundations.” These words arise from the assumption that black or dark is something bad and that white or light is something good, something to aspire to. Therefore, whenever someone wants to undermine something or someone, they just point out its proximity to blackness.

Much more obvious is the use of the word “negro” in its corrupted form “nego,” as a subject for accusatory exclamations in Brazil, such as “nego é fod*!” (black people are fu@#-up). As well as phrases like “quando preto não caga na entrada, caga na saída,” (literally, and most offensively: if black people don’t shit on their way in, they’ll shit on their way out) which has already been the subject of a criminal lawsuit and which, once again, makes the assumption that black people are to blame and characteristically make mistakes. There are also racist “jokes” based on the stereotyped social image of the physical appearance of black people: “nariz de batata” (potato nose), “cabelo de xaxim” (tree fern hair) or “cabelo de pixaim” (kinky hair), “boca de bueiro” (manhole mouth, due to full black lips), etc. criticizing a specific phenotype and revealing the biological racism of Brazilian society. These and other racist “jokes” were naturalized over many years, promoted by mass media and national comic personalities.

One of the least consensual and combatted facets of racism, while also one of the most disseminated, is racial banter. Racial banter oppresses black people through so-called jokes, without the actual need for the whip. It even pervades relationships between family and friends and is still not widely seen as a problem. But are these really jokes or are they a way to reproduce and update racist and prejudiced practices?

Evidence of this type of racism, with nation-wide reverberations, was recently seen on a Brazilian TV reality show with a large viewership. A participant compared the natural afro of a black participant to the wig of a caveman costume. This caused a strong reaction from the black participant and started a public debate about everyday racism.

Racism in jokes about the phenotype of black people still gets high ratings and its violence is still questioned. Many do not understand that ridiculing an afro is an attack on lives that have been subordinated, but which during four centuries of kidnapping, exile and slavery have flourished, reclaimed their curls and will not back down. Many laugh at Afro-Brazilians and reinforce police and penal biases, and the genocide of the black population. The reality show case echoed across social media.

To better understand how black people who are victims of these racist “jokes” feel, two Afro-Brazilians, Laura de Souza and Daniel Costa, were interviewed. The same questions were put to both interviewees. These accounts give us a small picture of what happened and still happens to the black population in Brazil.

Interview with Laura de Souza*

Born and raised in Nilópolis, a municipality in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, journalism student Laura de Souza, 21, who is a current resident of Barra da Tijuca, in the West Zone of Rio, has always perceived herself as non-white. It was only recently, however, that she started to see herself as a black person. Other people always said she was not black because she was not dark-skinned, something she immediately deconstructs in her first answer. Coming from a bi-racial family, in which the racial debate was absent, she previously adopted some whitening procedures—like straightening her hair—to feel more accepted.

Born and raised in Nilópolis, a municipality in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, journalism student Laura de Souza, 21, who is a current resident of Barra da Tijuca, in the West Zone of Rio, has always perceived herself as non-white. It was only recently, however, that she started to see herself as a black person. Other people always said she was not black because she was not dark-skinned, something she immediately deconstructs in her first answer. Coming from a bi-racial family, in which the racial debate was absent, she previously adopted some whitening procedures—like straightening her hair—to feel more accepted.

RioOnWatch: What is it like, for you, to be a black person?

de Souza: Well, understanding myself as a black person is relatively new to me. I always knew that I wasn’t white, but I also always knew that I wasn’t a dark-skinned black person because nobody, in my family or in the street, has ever used terms such as “preta” (black) or “neguinha” (another term for black) to refer to me. I’ve always been called “morena” (a black person with fairer complexion), “coffee with milk” or “washed out.”

From this introduction, you can deduct that I am mixed-race: my father is white, and my mother is black. Although his family is all white, her family has white and black people in it, so I was not raised in an environment where there was any type of racial education. Neither did I have anyone to talk to me about “being black.” Not that the black part of my mom’s family didn’t have their own considerations on the topic, as I found out later on. It’s just that the topic did not exist openly. These discussions never came up at family lunches, for instance.

In high school, most of my friends were black and they all had this awareness. But, then, one of my best friends, since her sister was studying journalism, started to have contact with black thinkers and took all of this information to school, where we used their ideas to discuss, as much as we could, the nuances about “being black” and “being black in Brazil.”

This moment, which I consider to be recent in my history, was crucial for my understanding that “pardos,” mixed-race people, are black too. And, for this reason, I was black as well. “What is it to be a black person?” is a question for which I, personally, don’t have an answer yet. And I actually suspect that few people do. What I’ve learned, in the meantime, is that it has to do with a very particular way of seeing, feeling and experiencing the world. It’s a black way of being in the world, which does not necessarily have to do with sadness or tragedy, but with a special way of being happy, of loving, of sharing and living in community.

RioOnWatch: Has being a black person meant that you have experienced “jokes” of a racist nature?

de Souza: Well, since you’re using quotations marks, I imagine you’re referring to racist situations disguised as jokes, right? Well, as I said before: I am not dark-skinned and, for a long time, my mom used to straighten my hair because I cried wanting straight hair like hers and my schoolmates’. So, in this sense, this made my childhood and the beginning of my adolescence “lighter.”

At the age of 13, I cut all my hair off to rid myself of the effects of the straightening. But they started calling me a lesbian at school and that made me start growing it out again. The problems with these “jokes” started there. Although, before that, I had other characteristics that provided more reasons for jokes: I was fat, I wore glasses and braces, I’ve always kept to myself and was a bit of a nerd. The whole combo. So, these “jokes” only really started after I began wearing my natural hair.

RioOnWatch: What was the content of these racist “jokes”? Did they involve phenotypical elements (hair, skin color and shape of the face for instance)?

de Souza: Well, it was always someone talking about my hair. Someone making nonsense comparisons, asking, while they cracked up, for me to get out of the way because they couldn’t see the chalkboard, or throwing spitballs so that they’d stick to my curls… I’ve had people take pictures of me in the street. Once, me and a friend, who also has curly hair, were waiting for the bus when two ladies in another bus, started staring at us, laughing, pointing, and taking pictures. I’ve had someone tell me to get my hair cut… many things.

RioOnWatch: Where do these racist “jokes” happen?

de Souza: Usually, at school. But I’ve heard a lot of “funny” comments at home, as well. Mainly from my maternal grandmother and from my dad. At school, I always talked back and always ended up at the headmaster’s office complaining against this or that racist student. At home, I only started to say that those comments bothered me after a while, and then I’d explain why they were wrong. My dad stopped, but my grandmother still makes these kind of clueless comments from time to time.

RioOnWatch: The way people talk about your biotype, has it ever or does it still affect you psychologically? How do you deal with this issue?

de Souza: At first it made me very angry. I used to get into fights all the time, and always kept my guard up. This was obviously not good for my psyche, and it started to tire me out. It really tired me out.

But, later on, I understood that the issue was not personal. People didn’t make fun of me because they didn’t like me. Yes, sometimes that was the case, but it was a bigger issue. As we say: it’s structural. So, I made up my mind to keep cool. To explain why it was wrong. Then, if the person keeps at it, I just walk away. I get up from the table. I leave the room. I do whatever it takes to show them, peacefully, that this type of “comment” is not acceptable.

Religion helps a lot with this, as well. I calmed down a lot, overall, after I became a Christian. So, in this type of situation, I always pray that God give me the wisdom to speak and the tranquility to act, because I know I am bigger than this. He makes me greater than all of this.

RioOnWatch: And how does your family position itself and guide you in relation to these issues?

de Souza: When I was younger, at the beginning, my mom used to tell me to fight back whenever I felt I could. But then she noticed it hurt me, so she suggested I just leave it alone. My brother was the same. He used to say things like, “Don’t you like your hair like that?! That’s the way you like it, right?! Then, you’re going to have to toughen up to have it like that.”

They were the only ones in the family with whom I talked about this kind of thing. Finally, this is what I decided: if the two of them stood by me, supporting me and giving me strength, I could beat the rest. It worked.

RioOnWatch: Have your relatives experienced this type of racism in jokes? How do or did they deal with this situation?

de Souza: Not that I know of. With them, it’s always been more explicit, since they’re dark-skinned.

RioOnWatch: In your opinion, is it racism or joking and why?

de Souza: Racism manifests itself in several ways. Not just racism, but several other types of prejudice… People always presume that these jokes are harmless, but my experience showed me that, at least in Brazil, most of the things that make us laugh are linked to the feeling of superiority that we feel in relation to another. I have always understood that being able to laugh, that being able to find something funny, has always been a way to feel better than someone else, indifferent to the feelings of the person who is the butt of the joke.

I understand that other forms of joking, of laughing, of making people laugh may exist, but I, in particular, can no longer dissociate one thing from the other. They are there together, blended.

RioOnWatch: In your opinion, is this topic still taboo for society? Do you think that society still has a lot to think about and change?

de Souza: There always is, isn’t there? If I said that Brazil’s already turned into the best place in the world do be black in, I’d be lying. But I do think that things have been worse…

RioOnWatch: What message would you leave for people who make this type of joke in bad taste?

de Souza: “Everyone’s an ass in some way. What makes you a good person is how much effort you put into no longer being an ass. It’s never too late to start trying, if you really want to.”

Interview with Daniel Costa

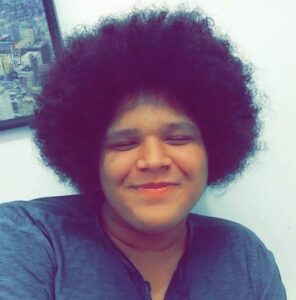

Born and raised in Ilha do Governador, Daniel Costa, 21, studies Defense and International Strategic Management at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and is a current resident of São Gonçalo, a city in Greater Rio, near Niterói. Since childhood, he has heard himself be described as neither white nor black. When he was young, he felt that people did not like him. Only after a long time did he come to realize that they were expressing their prejudice against the color of his skin and his hair.

Born and raised in Ilha do Governador, Daniel Costa, 21, studies Defense and International Strategic Management at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and is a current resident of São Gonçalo, a city in Greater Rio, near Niterói. Since childhood, he has heard himself be described as neither white nor black. When he was young, he felt that people did not like him. Only after a long time did he come to realize that they were expressing their prejudice against the color of his skin and his hair.

RioOnWatch: What it is like, for you, to be a black person? Has being a black person meant that you have experienced “jokes” of a racist nature?

Costa: Yes! Since I was a kid, when I was the “not quite black, not quite white” person, when I was the “color of cardboard,” besides the comments about my hair. In joking tones, but always carefully directed, I always heard people say that I was one of the ugliest people in class, that my hair couldn’t grow “without becoming a nest” or “becoming a hiding place.” [The “jokes” were] mainly [about] my hair, but also about skin tone, and face and body shape.

RioOnWatch: Where do these racist “jokes” happen?

Costa: Mainly at school, but also at church. Hardly ever at home.

RioOnWatch: The way people talk about your biotype, has it ever or does it still affect you psychologically? How do you deal with this issue?

Costa: I think so, yes. When I was a kid, I used to say that I wanted to use acids to make my skin lighter and to do a lot of plastic surgery. In the past, I even used acids on myself, which is dangerous. Not to mention the other less explicit problems which are also a result of these “jokes,” like self-esteem.

RioOnWatch: And how does your family position itself and guide you in relation to these issues?

Costa: They never gave me much guidance, except for some people on my mother’s side of the family, who are black. Mainly they tried to praise me, but it wasn’t very profound guidance or advice. I think that, as I became more aware, I was the one who ended up advising and talking more about this with my mom.

RioOnWatch: Have your relatives experienced this type of racism in jokes? How do or did they deal with the situation?

Costa: Yes, a lot of bullying at work, always feeling sad, but they had to carry on as normal.

RioOnWatch: In your opinion, is it racism or joking and why?

Costa: Racism. Of course there are relationships in which, with a certain level of intimacy, these “jokes” can end up sounding less vulgar and more like actual jokes. This happens mainly between black people, but generally it is a subtle way to naturalize and externalize racism.

RioOnWatch: In your opinion, is this subject still taboo in society? Do you think that society still has a lot to reflect on and change?

Costa: Yes, but the myth of racial democracy and the idea that “nowadays everything is racism” or “you can’t joke about anything anymore” make it difficult to even propose this debate. There is a process of raising awareness involved. A lot of people don’t see the evil in these “jokes.” They think that the intention of the person who makes the joke is more important than the feeling caused by the joke and felt by the other, the victim. Dealing with this is very complex. You can’t just be patient and didactic, but you also can’t act just for the “comeback” or in retaliation.

RioOnWatch: What message would you leave for those that make this type of joke in bad taste?

Costa: Try to change. Think that it’s not only you who is “joking” here. Hearing the same jokes, about the same features every day makes us start to believe the jokes. It messes with our subconscious, our self-esteem, our way of seeing ourselves in the world.

Conclusion

It is evident that both de Souza, a black woman, and Costa, a black man, agree that racism disguised as jokes is still treated as if it were normal, even within intimate relationships among friends and family. As a way of trying to avoid these so-called jokes, people seen as different try to fit into accepted standards, even if they do not regard the existence of these differences as legitimate. Jokes that cause depression, that hurt and mutilate physically or psychologically are not jokes. The people who make these racist, colorist, homophobic, sexist, etc. “jokes,” must understand this: you can’t go on claiming that everyday racism is a type of social integration. In reality, it is an instrument for enforcing racial hierarchy and oppression disguised as laughter. Racial banter is a major cause of low self-esteem and psychological trauma from childhood.

An emblematic and controversial case occurred last year in the interior of São Paulo. A video of a young man insulting his cleaner in a joking tone while she sang, shocked everyone with its racist and body-shaming comments, as summarized in a BBC Brasil article: “‘The girl who cleans our house comes here and starts singing so f*cking loud. And she says she wants to be a singer. She’s fat, black, with tough hair…’ says the boy, just before filming the young girl washing dishes and singing.”

The video went viral and outraged a lot of people. So the duo who recorded it came out in public and claimed that everything was a set-up to call attention to racism: a video about the real experiences of domestic employees, the majority of whom are black women who routinely experience racism in their places of work. But was it really just a set-up or an excuse so they could get away with a crime? For those wondering if it’s racism or a joke, have no doubt: if someone involved is not enjoying themselves and can be hurt physically or psychologically, it’s not a joke, it’s racism! It’s violence with a comic smile.

About the author: Currently in her third year of studies, Andreia Meireles, 23, is doing her degree in Social Communication, specializing in Journalism. A resident of Guaratiba, in Mato Alto, West Zone of Rio, she spent her early years in Vidigal, in the South Zone. She is an activist for the Movimento Juntos (Together Movement) and Rede Emancipa Rio (Free Rio Network).

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist who works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UFRJ) School of Fine Arts. Her goal is to use art to represent people who, like her, a young black woman from the periphery, are not always seen.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

*Interview translated by Trisha Ponti