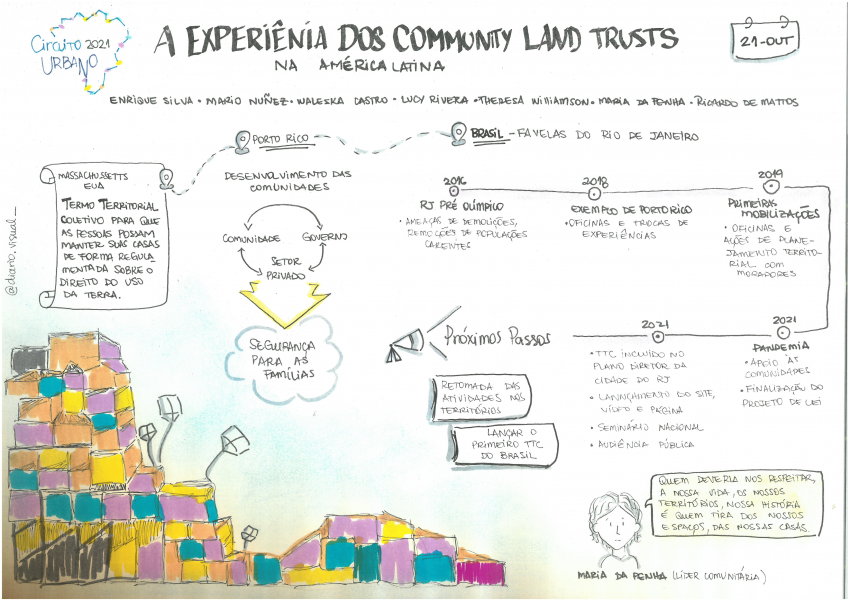

As part of the activities of the 2021 Urban Circuit and of the first ever International CLT Festival, the Favela Community Land Trust Project (F-CLT)* and Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña held the webinar “The Experience of Community Land Trusts in Latin America” on October 21. The event had the support of UN-Habitat, World Habitat, El Enjambre, Communities Strive Challenge and the Center for CLT Innovation. The event was moderated by Lyvia Rodríguez, Director of El Enjambre and Favela-CLT project assistant and lawyer Felipe Litsek.

“The Experience of Community Land Trusts in Latin America” featured community leaders, activists and representatives from civil society organizations from Puerto Rico and Rio de Janeiro, all of whom are involved with Community Land Trusts, presenting experience of how this tool can support the fight for housing in Latin America. The Favela-CLT is a model of collective land ownership and management in which the structures belong to individuals while the land is collectively owned, a system that respects both collective and individual interests and guarantees accessible housing in perpetuity to low-income populations. CLTs help protect against forced evictions and real estate speculation, reducing gentrification. Their actions go beyond housing, however, promoting community-building and development.

The event started off with Enrique Silva, Director of International Initiatives at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, reflecting on CLTs and explaining that they are “an alternative operational approach to private ownership of land and to the individual appropriation of land resources as income, [which become] a source of inflation of property prices, and of unequal access to housing and to land. The Lincoln Institute has been interested in CLTs for years because they provide us with a view of land tenure and of housing that promotes a deeper understanding of the important role played by land in the social and economic development of our communities. Particularly for those segments of the population that fight for a dignified, accessible and durable home.”

The event started off with Enrique Silva, Director of International Initiatives at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, reflecting on CLTs and explaining that they are “an alternative operational approach to private ownership of land and to the individual appropriation of land resources as income, [which become] a source of inflation of property prices, and of unequal access to housing and to land. The Lincoln Institute has been interested in CLTs for years because they provide us with a view of land tenure and of housing that promotes a deeper understanding of the important role played by land in the social and economic development of our communities. Particularly for those segments of the population that fight for a dignified, accessible and durable home.”

Latin America already has a successful Community Land Trust experience in San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. Mario Núñez, Executive Director of the Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña, and Waleska Castro, Vice President of the Fideicomiso, explained that this CLT is found in a strategic part of the city and that it currently owns over 210 acres of land. The Puerto Rican CLT won the 2015 World Habitat Awards.

The creation of the Puerto Rico CLT was no easy feat. In the beginning, the government wanted to distribute individual land titles, but the population feared the area’s gentrification and started to study tools that would allow for collective land ownership as an attempt to mitigate this process.

Núñez explains: “In the particular case of the Caño Martín Peña, we recognized that once the canal [next to the community] was dredged, our plot of land would be highly valued. There would be a high capital gain due to the privileged location we are in, and that would make it attractive to speculators… On the other hand, we figured that proposing the Community Land Trust and the collective property was a way to guarantee social justice to those of us who have lived on this land for many years and who have occupied this settlement for decades, quite often without public services.”

Castro highlights: “Being under the CLT means, above all, protection. You feel protected. No one, no government can come here and say ‘you have to leave this place,’ or ‘we’re going to buy this land so everyone has to move out.”

After hundreds of meetings, studies and internal discussions, the communities of the Caño opted for a Community Land Trust and are currently structured through three organizations: the G-8, a grassroots organization that represents the Caño’s eight communities; Fideicomiso de la Tierra, the organization that holds the land title and manages it on behalf of residents; and the ENLACE Project, a public company that carries out, plans, develops and coordinates the district’s comprehensive development plan together with residents.

Lucy Rivera, president of Caño Martín Peña’s G-8, emphasized the importance of community engagement and of the decision-making processes that happen collectively in a well-functioning Community Land Trust: “It’s important to have an organized community. Without this mobilization, there would be no CLT… Without a good organization, we would not be able to deal with sudden political change; we would not be respected by our own neighbors and by community residents. Due to the way we organize ourselves, they trust what we do, what we say. Therefore, it is very important that community organizations work hard towards a single goal, that it is a collective and not an individual goal.” At the Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña, meetings and assemblies are held with all members of the CLT, as well as with residents that have not yet opted for the model. For those who cannot participate in one of their meetings, information is also provided through the community newspaper, Raíces del Caño.

Contextualizing the Brazilian situation, Theresa Williamson, Executive Director of Catalytic Communities, gave background on how the preparations for the World Cup and Olympics a decade ago impacted Rio’s favelas. The period was marked by enormous real estate speculation and forced evictions to peripheral areas. In searching for a protective solution for favela residents, CatComm began studying the possibility of implementing Community Land Trusts in Brazilian favelas. However, without knowing a case, anywhere in the world, in which the model had been applied to an informal settlement, the idea seemed like a pipe dream. Learning about the implementation of Puerto Rico’s CLT thus became crucial to the process of imagining a CLT applied to Rio’s favelas. It was only after the Rio Olympics, in 2016, that CatComm learned about the Puerto Rican CLT when it was announced that the Fideicomiso had won the World Habitat Awards. That was when CatComm sought out the Caño for an article, published on RioOnWatch, giving rise to a partnership that furthered the activities of the Brazilian CLT Working Group with the visit of a delegation from Puerto Rico to Rio in 2018. This endeavor was, in fact, supported by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Enrique Silva.

As a public defender in the Land and Housing Rights Nucleus (NUTH) of Rio’s Public Defenders’ Office, Ricardo Mattos reported that the distribution of individual land titles to the low-income population in Brazil can be a concern due to the harassment residents may suffer from the real estate market. This is what made him interested in CLTs: “Gentrification happened routinely in favelas that got land tenure… CLTs attracted me precisely for the possibility of protection they offer after formalization, after land titling takes place. Because even with the public defenders acting, it’s always been a very difficult choice: what [land titling] tool to use and whether it truly is advantageous to promote the locality’s titling knowing that titling might make the community even more vulnerable [to speculation and displacement].”

Maria da Penha, a resident of the Vila Autódromo community and cofounder of the Evictions Museum, talked about her life experiences: “Those who should respect our lives, our spaces, our history [public officials] are exactly those who take us away from our territory, from the homes we worked so hard to build to be in that place. And when the monetary value of the area we built goes up, the city government, our authorities, come and want to take us away by force.” Regarding the CLT, she believes that “it is a wonderful tool, one that offers protection to communities. Especially because it can be implemented in a favela that is already there. And it makes it easier for us to continue living on our land.”

From this perspective, of the benefits provided to the community, Núñez described how the collective ownership of land is a tool for guaranteeing the population’s permanence in their territory. In the case of the Caño Martín Peña, they knew that public interventions and individual titling would bring growth in the area’s real estate value, and with the CLT this increase did not lead to gentrification. In his view, Community Land Trusts are a way of guaranteeing social justice to those who have been living on the land for decades. He underscores that, as in the case of Puerto Rico, CLTs serve as tools that can be adapted to each community’s needs and contexts.

Setting up a Community Land Trust is hard work. It took the Caño Martín Peña over 700 meetings before choosing the tool and then a lot of effort was needed to approve Law 489 of 2004 that establishes and protects the Caño Martín Peña CLT.

For Brazil, “we’ve been thinking about CLTs as a model to regularize pre-existing homes and communities. Because, in Rio de Janeiro, almost one fourth of residents already have a home in the favelas. And many of these people, like Maria da Penha, want to stay, want to remain, want to see that territory improve. But they want to see this happen from the residents’ perspective, under the residents’ ongoing management, keeping the assets, the qualities that were built there… maintaining favela qualities where they are. People built a culture, a living, an economy, in other words, everything, locally. And CLTs value that. A CLT is not going to arrive in the form of an individual land title that carries the risk of pulverizing this collectivity, that is a great asset, a great quality of favelas,” says Williamson.

Watch the Live Event, “The Experience of Community Land Trusts in Latin America” Here:

The Experience of Community Land Trusts in Latin America – English 102121.mp4 from Greg Rosenberg on Vimeo.

*Both RioOnWatch and the Favela Community Land Trust (F-CLT) are initiatives of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).