This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

“Students always ask me: teacher, are you leaving? I say no, this is my place.”

It is with this statement that schoolteacher Jacqueline Lucia Guimarães, 42, explains her relationship with Morro do Palácio. The favela community is located in the Ingá neighborhood, a prized region of downtown Niterói, bordering the campuses of both the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) and of the Aurelino Leal Public High School, where Guimarães has worked for six years.

Born and raised in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region, the educator moved to Rio’s sister city, Niterói, when she started working towards her Mathematics degree at UFF, in 1998, at a time when there were no affirmative action policies supporting black students. A popular educator, civil servant for the Rio de Janeiro Secretary of Education (SEEDUC), and a resident of Morro do Palácio herself, Guimarães’ trajectory reveals the mishaps young black peripheral residents face to gain admittance to and graduate from university. It also shows how access to university can transform lives and increase black representation in the classroom.

“I get the feeling that students are very surprised when I walk into the classroom, because when I enter the room, they already know I live in Morro do Palácio. When I walk in, I see their surprise… I don’t know if it’s because I’m Afro-Brazilian or because I live in their community,” says Guimarães.

First in her family to attend university, the educator had to move into the Fluminense Student House—which is currently closed—in order to finish her college education. She was an active participant in the university’s student movement and had a scholarship to the School of Engineering. It took Guimarães eight years to finish her degree, not only due to the curriculum’s difficulty, but also because she attended classes, held a teaching internship, and worked at the Pré-Vestibular Social da UFF (UFF’s free college entrance exam preparatory course).

Since she was still teaching college entrance exam prep when she graduated in 2006, Guimarães did not want to return to the Baixada Fluminense, where she was raised. She rented a studio apartment in downtown Niterói. However, with the arrival of two of her brothers to live with her, also to pursue their studies, the lack of space left her “dissatisfied.”

Looking for a house to better accommodate the family, she went up a steep road and asked a lady if there were any houses available for rent. “She had never seen me, but told me that if I kept going up, there was a gentleman at the end of the street who rented houses. I went. In fact, it took me a month to figure out I was living in the Morro do Palácio favela,” she adds, laughing.

That was where she met Mr. Antônio. He showed her a house, and Guimarães asked for seven days so that she could save up the rent money. To her surprise, he agreed. “That was it: his word and mine, nothing on paper, nothing formal. I didn’t think he was going to give me any credence, but he did. I came back seven days later, closed the deal, there was no receipt, but I trusted him,” she recalls.

Ten days later, she moved to Morro do Palácio. The year was 2008. And she has not left since. In 2014, she was able to buy a house in the community.

“It’s amazing how we start socializing and get used to a place. I came to better understand people’s routines, human beings… but also the illicit schemes. I made a comparison regarding violence, especially in relation to drugs. My conclusion was that these issues are not specifically inside the community. They might be more concentrated here, but outside it’s the same. Violence does not choose an address or social class.”

Guimarães adds: “I also analyzed people’s kindness. It’s different here. Respect, appreciation; the care people show for each other is different. Sometimes, when something violent happens here, students ask me: teacher, are you leaving? I say no, this is my place. Morro do Palácio is my place. I feel welcome here.”

The Classroom: A Space of Representation

“I thought that this is my place. Inside Morro do Palácio and in this school’s classroom, in which I am my neighbors’ teacher.”

Since 2003, through Law 10,639/03, it is mandatory in Brazil to teach Afro-Brazilian and African history and culture in both public and private elementary and secondary schools. The law led historical figures such as Tereza de Benguela—who led a quilombo in the state of Mato Grosso in the 18th century—to begin to be mentioned in classrooms. This was a claim and a victory of the Black Movement.

However, the expressions of inequality brought on by structural racism in the construction of spaces are far from over. At a pedagogical level, the development of Afro-Brazilian history and culture teaching, in practice, ends up depending on the school community taking action.

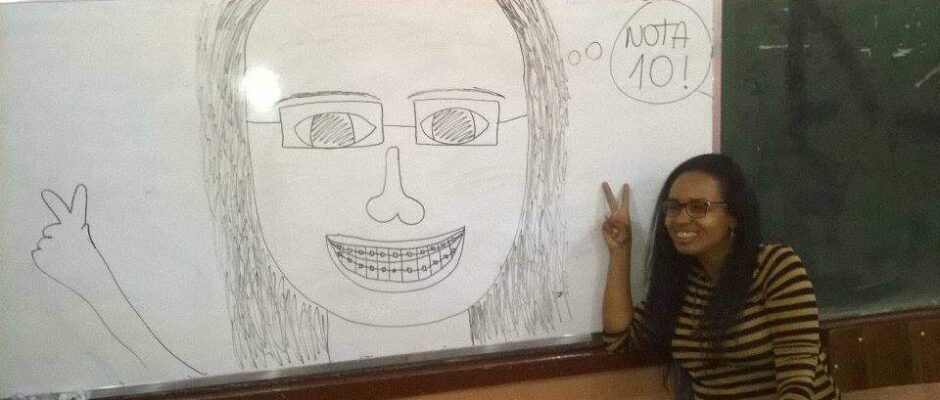

Working for a public state school since 2012, Guimarães’ classroom experience reveals how the manner in which the black identity debate is included within the school can influence students’ and teachers’ aesthetic choices, as well as their empowerment.

“The one thing I liked the most at the Aurelino Leal Public High School was the students’ identity. Do you know why? At the time, I used to straighten my hair. But there, I saw teenage girls with their full, natural, curly hair. I thought it was beautiful to see this black, Afro-Brazilian identity. It caught my attention, because at the other school where I taught, I did not find this identity… neither outside, nor within me,” she says.

The teacher’s testimony reveals the importance of an educational environment that generates feelings of belonging and representation. “At the first school where I worked, I had natural hair, but I straightened it when I started there. I realize today that if I had entered a classroom for the first time at my current workplace, I would never have straightened my hair. I remember a certain shock of inner thought extremely well. Of course, we can’t generalize. Every black woman should wear her hair as she pleases: straight, natural… but I was shocked by the identity of the students at the school I work at now, and by how much they’ve taught me.” Guimarães concludes: “I learned and experienced this identity rescue through and with my students. I’ve found this delightful. It’s made me think that this is my place, in Morro do Palácio, inside this school’s classroom, in which I am my neighbors’ teacher.”

School Census: Precarious for Educational Analysis by Skin Color/Race

The state of Rio de Janeiro is among the places with the highest number of public schools in the world, with a total 1,230 state schools distributed between 92 municipalities. According to a SEEDUC survey, among the 729,000 elementary and secondary students in the state, 320,000 enrolled students identify themselves as black and brown, representing 43.89% of the student population served by the state.

Despite this overall black population representation, the state does not have information on the number of black and brown teachers working in its schools. In the last survey conducted by the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP) in 2020, no data by race and skin color exist either on the number of teachers working in basic education, at the school level, in any of the Brazilian states or municipalities. The school community research is conducted annually by INEP.

The absence of these data draws attention because race and skin color have been mandatory collection variables in the School Census since 2005, as established by Ordinance No. 156 issued in 2004, at the request of the Ministry of Education (MEC). The inclusion of the item “race/skin color” by self-declaration in the census was intended to allow, through the data, the implementation of affirmative action policies by state, municipal and federal governments. This change in the School Census met a historic demand for representation defended by grassroots movements and was advocated for by the Secretary of Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion (SEDACI).

The absence of these data draws attention because race and skin color have been mandatory collection variables in the School Census since 2005, as established by Ordinance No. 156 issued in 2004, at the request of the Ministry of Education (MEC). The inclusion of the item “race/skin color” by self-declaration in the census was intended to allow, through the data, the implementation of affirmative action policies by state, municipal and federal governments. This change in the School Census met a historic demand for representation defended by grassroots movements and was advocated for by the Secretary of Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion (SEDACI).

However, in the School Census statistics, there are only data of “race/skin color” in reference to the number of enrolled students. Teachers are only segmented by gender, age group, education level and academic background.

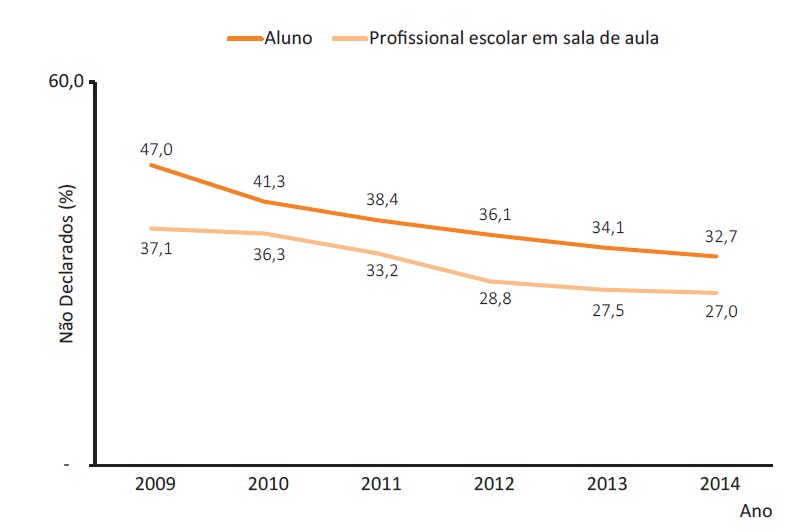

In the report “Skin Color or Race in Educational Statistics: An Analysis of INEP Research Tools,” published in 2016, the institute states that “two years after [the ordinance], guidelines for field data collection [skin color/race] were included in the Instructions Booklet [of the School Census].” The agency also emphasized the “need to comply with instructions for obtaining this specific variable, considered mandatory, from the beginning of field research,” both for teachers and for students.

The response choices available for the “skin color/race” question are similar to those presented by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in its surveys, with the addition of the “undeclared” option.

However, the institute notes that: “dialogue with state and municipal partners, in addition to on-site visits, allowed us to verify that several schools did not show the ‘skin color/race’ field neither in their student registration forms nor in the administrative records of classroom school professionals. As a result, a portion of undeclared responses may actually be the result of schools not obtaining this information.” The study concludes: “Despite being a mandatory reporting field, the relatively high rate of responses to the ‘undeclared’ still makes the School Census a precarious tool for educational analyses by skin color/race.”

Education in Brazil is a constitutional right, guaranteed for all. But for the country’s black and brown children, particular challenges that go beyond mere access to education still need to be faced: there is not enough representation in the classroom to ensure black—and white—populations have access to an education which, both in discourse and practice, fights structural racism.

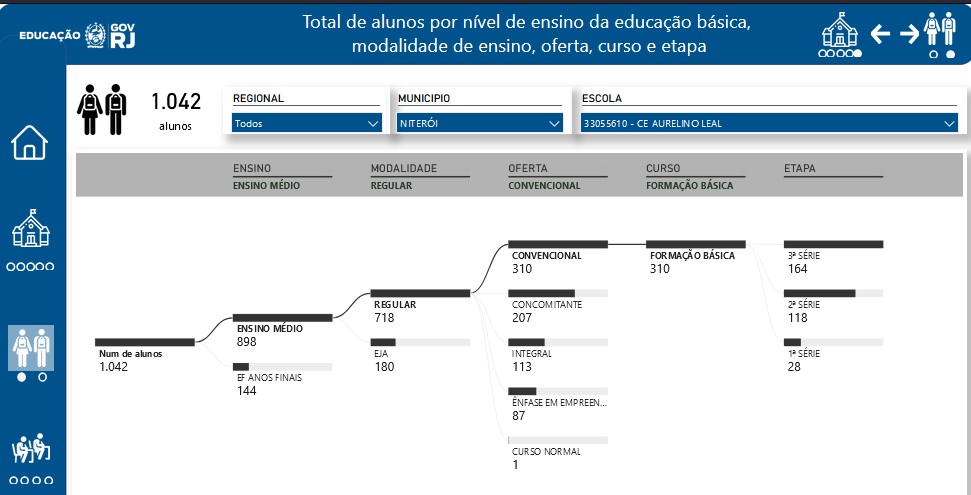

Small efforts, by popular educators and students, in classrooms across the country, and experiences such as those of teacher Jacqueline Guimarães and of students at the Aurelino Leal Public High School, bring hope. In total, the school numbers 1,040 students, of which 180 are enrolled in Youth and Adult Education.

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist and a popular communicator at heart. A black feminist, member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she works as a reporter and network manager at RioOnWatch. A fair-skinned black woman, born and raised in a favela, Lima currently lives in Rio’s periphery and is a doctoral student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).

About the artist: An undergraduate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UFRJ) School of Fine Arts, Raquel Batista, 19, was born and raised in Campo Grande and currently lives in Engenho de Dentro, in Rio’s North Zone. A visual artist who works as a photographer and illustrator, her goal is to use art to represent people who, like her, a young black woman from the periphery, are not always seen.

This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.