This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

Abdias do Nascimento transformed his life into a fervent fight against racism. It was not enough for this great Brazilian intellectual to be an activist, politician, professor, journalist, artist, writer and playwrite. He was also an actor on an empty stage of representation. It was a period when white actors used makeup to darken their skin, because black characters were needed here and there. But the chosen actors had to “adapt” their acting to the character’s ethnicity. “Acting out blackness,” at that time, only meant wearing makeup, the famous “blackface,” so widely criticized by black movements. It was 1941, and in very successful plays such as O Demônio Familiar (1857), based on a three-act comedy by José de Alencar, or Iaiá Boneca (1938), written by Ernani Fornari, the roles of black characters—who obviously should have been interpreted by black actors—were depicted as grotesque caricatures. White faces painted black.

Returning from a trip to Lima, Peru, in 1941, Nascimento was determined to create theater that was 100% black. With this goal, the Experimental Black Theater (TEN) emerged three years later in 1944, in Rio de Janeiro, proposing to rescue Afro-Brazilian cultural values. His first students were recruited among blue collar workers, domestic workers, favela residents without defined jobs, as well as lower-class civil servants. In its first year of existence, TEN had close to six hundred students. However, its success bothered racists. Plays more faithful to our daily cultural reality, staged by the theater company—such as Filhos de Santo (1948), by José Morais de Pinheiro, set in Recife and which intertwines issues of Afro-Brazilian religious mysticism from Candomblé with the story of striking workers persecuted by the police, or even Black Angel (1946), written by Nelson Rodrigues, with a plot focused on the marriage of a black man and a white woman—were censored and persecuted, both by civil society and the media.

Were it not for the Experimental Black Theater, which was ahead of its time, it is possible that the performing arts and other forms of cultural expression starring black men and women would be restricted to ghettos even today. It is certain, however, that Abdias do Nascimento’s TEN is fundamentally connected to a great promoter of current black performing arts, which operates in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region: Grupo Código. The theatrical group has deeply anchored political engagement and activism in the city of Japeri—a territory possessed of a dense political reality—making it almost completely impossible to dissociate themselves from local reality through poetic, playful or escapist freedoms. Even if these are present in the script, inescapable daily life prevails.

Part of the inescapable daily life of Grupo Código, which turned 15 in 2020, is the goal of surviving with its cultural productions in these pandemic times. Mainly formed by black and peripheral residents, the group is a mixture of theater company and workshop, NGO, and cultural center. Grupo Código has more than eleven shows in its repertoire, of which the vast majority are narratives constructed around Brazilian peripheral bodies, female and black, in their most varied dimensions. One might then ask: how can you create “fictional” elements from the daily life of characters who can barely detach themselves from a reality that extrapolates perverse elements such as racism, sexism, and the criminalization of poverty? Can other realities besides these everyday occurrences and experiences serve as a laboratory? The collective seeks to break these barriers.

A few of these concerns have already been researched. Grupo Código was one of the theater collectives included in Marina Henriques Coutinho’s doctoral thesis The Favela as Stage and Character, and the Challenge of the Subject-Community, published in 2012. The thesis sought to understand artistic productions based on the various relationships between theater and community, and how this directly influences the creative processes developed through such relationships. As developed by theorists José da Costa and Cristophe Bident, the concept of “traversed theater” arises from this involvement with the territory, with other media and artistic expressions—dance, sound, video, music, new technologies, visual arts, etc.—blending with theater. Performance locations are free: tents, shopping malls, train cars, public squares, streets, boats, buses, etc. From there, mechanisms are developed through specific actions such as the insertion of the social context in the dramatic and aesthetic structure, influencing the scenic-dramaturgical results of the spectacle.

This is what happened with the enactment of Yaperí, That Which Floats (2017), an artistic conception of Ponto de Cultura Peneira—a Ministry of Culture-recognized organization that promotes multicultural practices—in partnership with Grupo Código. Created in the form of a traveling drama, Yaperí is a poem that honors the city and was performed in its streets with its final acts culminating in the main square, where aesthetics and symbology capture popular everyday elements, such as the vendors on the SuperVia trains. In its debut, in August 2017, the collective creation happened between actors and members of the local population.

Another show, Tracks, came about through a public bid issued by industrial social service agencies SESI/FIRJAN that sought new theater talents, and whose script was signed by playwright Suellen Casticini, a resident of Mesquita. In the narratives of female characters inserted in the universe of train vendors—including nods to the prison system and to faith as a business—we perceive selling as a lonely task, as one more addition to women’s second shifts. In the play, a male vendor who accidentally kills a co-worker is arrested and becomes a pastor. It’s a way of criticizing how certain churches influence power in some cities.

Actress Nil Mendonça performed in both Yaperí and Tracks. Born in Rio’s central region, in the neighborhood of Estácio, Mendonça’s family moved to Japeri when she was seven and she has remained in the city since. Mendonça has been involved in artistic activities since she was a child. A resident of the Engenheiro Pedreira district, which is still a rural area, she feels she missed out on opportunities which could have developed her cultural skills. She only rediscovered theater when she went back to school and met a teacher from Grupo Código’s cast who offered workshops on site. Before acting, Mendonça pursued writing in the newsroom of Japeri Online, one of the region’s few media outlets.

Actress Nil Mendonça performed in both Yaperí and Tracks. Born in Rio’s central region, in the neighborhood of Estácio, Mendonça’s family moved to Japeri when she was seven and she has remained in the city since. Mendonça has been involved in artistic activities since she was a child. A resident of the Engenheiro Pedreira district, which is still a rural area, she feels she missed out on opportunities which could have developed her cultural skills. She only rediscovered theater when she went back to school and met a teacher from Grupo Código’s cast who offered workshops on site. Before acting, Mendonça pursued writing in the newsroom of Japeri Online, one of the region’s few media outlets.

Asked about the two plays she was in, both of which analyze the reality of the Baixada Fluminense and its population, and about the “non-distinction” between facts and “fiction” in the theatrical composition of certain characters she performed in Grupo Código plays, Mendonça replied:

“As an actress, you need to make choices about what to do in a specific role, what kind of research needs to be done… I prioritize the theatrical production of black women and black men from the periphery. Because it is important, within your artistic process, to define what you identify with. I prioritize the black and peripheral body that is active in that moment. Although I feel comfortable playing roles that are like my reality, I also believe we should occupy spaces that need to be occupied. We need to echo various theatrical forms available in the Baixada and Rio as a whole.”

A Democratic “System?”

Russian actor and educator Constantin Stanislavski (1863-1938) created a system for preparing actors’ and actresses’ performances that stimulates psychological realism and living out authentic emotions on stage. The method employs an excessive emphasis on emotional memory, reconstructing actors’ personal experience as a function of acting. He concluded that the actor should strive, as much as possible, to represent real life. When role and actor connect, the role comes to life.

There was no way Stanislavski could have envisaged his method being used by black actors and actresses from the peripheral regions of Baixada Fluminense, something unthinkable in his time. Neither was his method imagined for a non-white, non-European audience. However, it is undeniable that his system allows actors to explore the possibility of bringing together experiences provided by episodes of racial or class prejudice and the psychological construction of black and peripheral characters, performed by individuals from these territories. Actress Juliana França explains:

“In the last works I participated in, fiction and reality unfortunately mixed a lot. It is always important to try to understand how far this reality can serve as material for creation. Reality is very harsh, and I always need to make sure that that specific character reflects a reality that is still very unequal, although that is not me. And, in this way, I manage to create some space so I can distance myself and have an outsider’s view of what I’m creating and what I’m feeling… In a society where social markers are inscribed on one’s body, I find it hard to disassociate one thing from the other. After all, this is a black woman’s body. My body is my own flag. Militancy happens in several, distinct ways; I believe change happens through small and through large cracks. So, when I’m working with a crowd that is mostly from Rio’s South Zone and I propose that filming also take place in the area where I live, that is, in Japeri, Baixada Fluminense, and that actually happens, something breaks. A ‘de-localization’ happens.”

In 2009, França was invited to join Grupo Código’s professional company. She has been in practically every one of the Group’s performances since and has won awards at theater festivals as a supporting actress. In 2015, she began studying to break into the audiovisual market. In 2019, she starred in her first short film, Neguinho, by Marçal Viana for which she won over five awards for her performance. Scripted and directed by Viana, the film covers specifically the lack of representation and racial segregation in the school environment. Inspired by a true story that happened in Duque de Caxias, the narrative follows a teacher who asks a student’s mother to cut her son’s afro, allegedly in the name of hygiene, since in the teacher’s racist view the hairstyle is dirty. Hers is a form of social and aesthetic “cleansing.”

França explains that to play Jessica, her character in Neguinho, she created a list of songs she believed her character would like: “Before shooting, I would put on my headphones and dive into Jessica’s world, which would then become my world too. Obviously after hearing ‘cut’ there were still some remnants left, but they were easier to dilute.”

Goodbye to Rita Diva

The coronavirus pandemic stirred the hearts and minds of the students, employees and collaborators of Grupo Código. Between planning and organizing humanitarian efforts, such as the distribution of basic foodstuffs that included bottled water, personal hygiene products and face masks, while also trying to balance the books through access to resources via the cultural promotion Aldir Blanc Law, all members had to deal with the loss of Rita Diva. One of the founders of Grupo Código, Rita Diva was yet one more fatal victim of coronavirus and died in April 2021, at the age of 41.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Rita Diva – Living memory of a star

This first of the month is emblematic to us for many reasons for it’s been a month since our beloved Rita Diva went away to shine with the stars. On International Workers’ Day, we would like to celebrate the life of this tireless worker for culture and education.

Rita de Cássia da Silva, daughter of a janitor and domestic worker, was a teacher. She coordinated a children’s educational unit in the city of Japeri. She was very active both in the city’s cultural scene and in its political and social movements. At the beginning of the pandemic, she organized a large clothing and food drive. In 2021, Rita became head of the Culture Secretariat, under the administration of Mayor Fernanda Ontiveros (PDT). Rita used to dress up as Santa Claus at Christmas and as a bunny at Easter. Mendonça says that “Rita made the people of Japeri believe in something. I have a very maternal relationship with her, she was always taking care of everyone.”

“Rita Diva was always the closest person I had in Grupo Código, the only one able to replace my tears with smiles. It was through her energy and will to live that I began to look at life with hope. The feelings she conveyed to me joined with the possibility brought by Código to focus these feelings on artistic works. That’s when I started investing more in poetic writing and venturing in front of the cameras,” says Grupo Código’s communications coordinator, Patrick Lima, who debuted in 2017 as an audiovisual producer and recently concluded the documentary Being Black in Japeri, born from a desire to portray positively the city with a focus on Black Awareness Day.

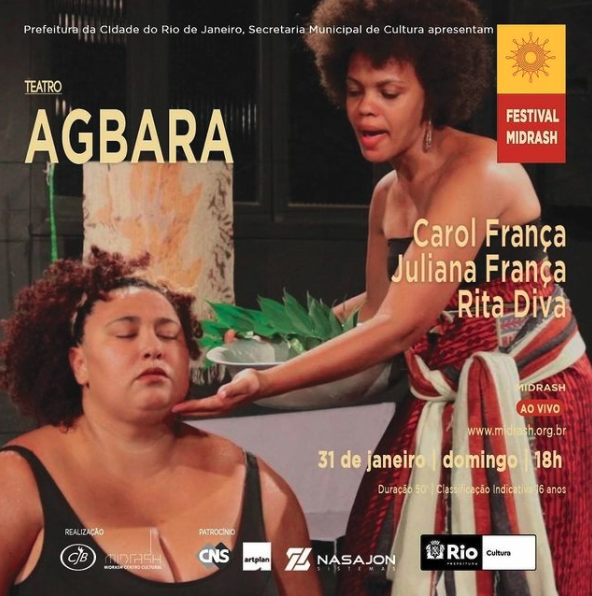

Between 2019 and 2020, Rita Diva staged the play Agbara (“power” in the Yoruba language), a show that addressed fatphobia, a prejudice she knew well, the black woman’s resistance, and black feminism in the face of a patriarchal society.

On April 3 of this year, the day of the actress’ death, Japeri Online organized a special live event on her career. In August, her militancy, dedication to art and love for life, for her friends and for Japeri itself resulted in yet another tribute. An award organized by Japeri’s Department of Culture, under the Aldir Blanc Law, and with resources from the Municipal Fund for Culture, was named in her honor. The Rita Diva Award—which rewarded 60 individual cultural productions developed in Japeri, in several areas, with a prize of R$2,500 (approximately US$445)—represented the continuity of the dream of a woman who dedicated her existence to education and theater, always with a smile on her face. Her legacy now continues in those who were captivated by her love and energy. A black, overweight woman from the periphery, Rita Diva used to say that as long as there was oppression, she would be resistance. Perhaps life will once again imitate art and we will soon have a play from Grupo Código inspiring us to be more like Rita Diva.

About the author: Fabio Leon is a journalist, human rights activist, and media advisor for Fórum Grita Baixada.

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist and works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at UFRJ’s School of Fine Arts.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.