On November 30, 2021, the Memory and Truth Commission of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (CMV/UFRJ) livestreamed the episode “The Black Population and Favela Residents Under the Dictatorship,” one of six in the “Countless” series, an audiovisual project aimed at bringing visibility to the stories of groups affected by the 1964-1985 military dictatorship in Brazil. Covering subjects often overlooked in traditional narratives, the event was broadcast on the university’s Science and Culture Forum YouTube channel, and followed by a roundtable discussion.

The discussion was led by Lucas Pedretti, a researcher at CMV/UFRJ and writer of the episode. Participants included Gabrielle Abreu, a historian and researcher at the Institute of Religious Studies (ISER); Itamar Silva, coordinator of the Brazilian Institute for Social and Economic Analysis (Ibase) and a researcher at UFRJ’s Citizenship University; Marco Pestana, a historian and professor at the National Institute of Education for the Deaf (INES); and Filó Filho—better known as Dom Filó—a cultural producer and executive coordinator of the Cultne collection, the country’s first TV channel dedicated entirely to black culture.

The discussion prompted reflections from researchers and activists, creating a broad overview of the dictatorship in Brazil. One of the episode’s themes, which also came up during the conversation, was the repression of black balls during the 1970s by the military dictatorship. During this period, government officials began to investigate and criminalize artists, intellectuals, and civil society groups.

The black balls drew crowds from the periphery, grooving to the beats of soul, funk, and samba-rock. In Rio de Janeiro, groups like Soul Grand Prix and Black Power stood as examples of musical resistance against the policies of the time, resulting in the persecution of their producers by the military regime. Dom Filó, the first to speak during the livestream, was one of these producers. In 1976, he was arrested for hosting black dances in Rio de Janeiro.

The story is told in the episode “The Black Population and Favela Residents Under the Dictatorship,” narrated by Dom Filó himself. Captured as he left the headquarters of renowned Renascença club, Dom Filó spent a night in a dark, cold room. With blurred vision, he struggled to see those around him. After enduring psychological torture, Dom Filó was released hours later in the North Zone neighborhood of Lins de Vasconcelos. Using contemporary documents and newspapers, the video illustrates that Dom Filó’s experience was not an isolated incident.

In discussing this part of his story during the livestream, Dom Filó shared: “We lived through a sinister period of military dictatorship in our country. For 21 years, we endured the ominous grip of authoritarianism, stifling the intellectual growth of the Brazilian people. Positioned at the base of the pyramid, Afro-Brazilians faced prejudice and explicit racism, all masked under the guise of racial democracy. But every action has a reaction. They didn’t anticipate that the focal point of resistance would emerge against that very dictatorship, within that chaotic backdrop, especially here in Rio de Janeiro. A few individuals made all the difference. I highlight those young people who, through music, managed to wield it as a tool to build a new identity, a new behavior, a new aesthetic. This remained hidden for many years, absent from mainstream media.”

During the livestream, Dom Filó recounted his experience as a guest speaker at the First Continental Conference on Afro-Latin American Studies organized by the Afro-Latin American Research Institute (Alari) at Harvard University in December 2019. His lecture focused on the importance of the Black Rio movement. Reflecting on the conference, he recalled: “During the meeting, they asked me a question, among many others, mainly because they were scholars and I was the subject—in other words, the one who had lived through that whole process… they asked me what it had been like to be a public enemy of the Brazilian State and to have survived underground. I stopped, thought it over, and everything just came flooding back. And this is what I answered: ‘I had luck and the protection of my ancestors on my side. If I hadn’t had that, I wouldn’t be here telling you this story.’ Really, I was very lucky, because plenty of my companions didn’t follow the same path, they weren’t so lucky. The boldness of my youth tested that luck. You all have no idea what that period was like.”

Revisiting memories from the 1970s, Itamar Silva also shared his experiences. “I lived my innocence as a young teenager from the favela in the 1970s… I was 13 or 14 years old, and I had an uncle serving in the army. On more than one occasion, he returned home furious because he was forced to repress students… sometimes he couldn’t come home because he was called in to work. They were putting together a group to repress students, and he was outraged by that. At the time, he wasn’t politically aware of what was happening, but it certainly had a strong effect on him. He explicitly stated that it was because he was forced to stay in the barracks. But I don’t think that was it. In reality he fundamentally opposed the whole procedure [of repression], to the extent that he later on became an activist.”

Silva spoke about his trajectory as a journalism student in the 1970s and his involvement in the Black Movement. He also drew a timeline from the dictatorship to the present, reporting on State repression and control over favela organizations during the dictatorship.

As recounted by Silva, the Federation of Favela Associations of the State of Guanabara (FAFEG) was created in 1963 in response to the forced eviction of the Morro do Pasmado favela in Botafogo. However, during its creation and expansion, FAFEG faced political persecution. Silva shared that that the Santa Marta Favela Residents’ Association was created in 1965, and during that period, several FAFEG leaders were already being persecuted, with some even being arrested.

“Here in Santa Marta, specifically, the president told me in an interview that [during the dictatorship] he was barred from making any move, any protest, or any claim due to police pressure and control. Police looked for communists including within residents’ associations.” — Itamar Silva

According to Silva, the dictatorship’s control over favela organizations is reflected in current State control policies.

“For those of us who live in the favela it’s obvious. As far as I’m concerned, we’ve always lived under strong State control. This persecution wasn’t made explicit for those who were living in the favela at that time [of the dictatorship]… I think that, today, we live the consequences of that period, of this [dictatorial] training that infected and contaminated the police… today, the favela is no longer seen—by the authorities, the police, the armed branch of the State—as a lair for communists, a center for revolutionaries. But it’s viewed as a place that it [the State] needs to control and eliminate. The logic we live with today is the same.” — Itamar Silva

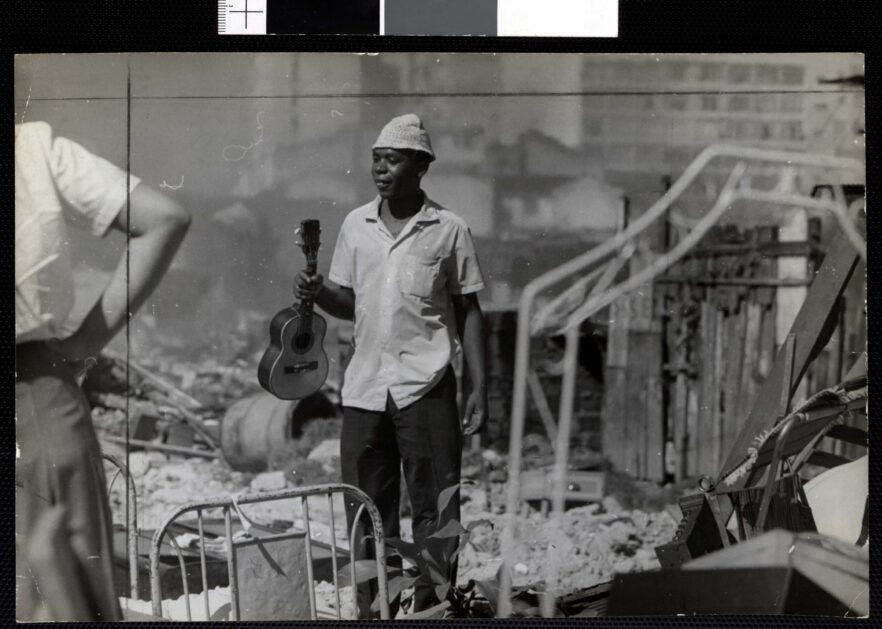

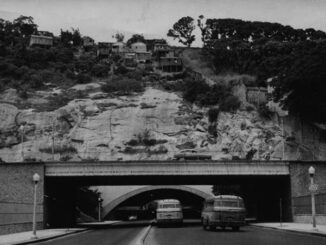

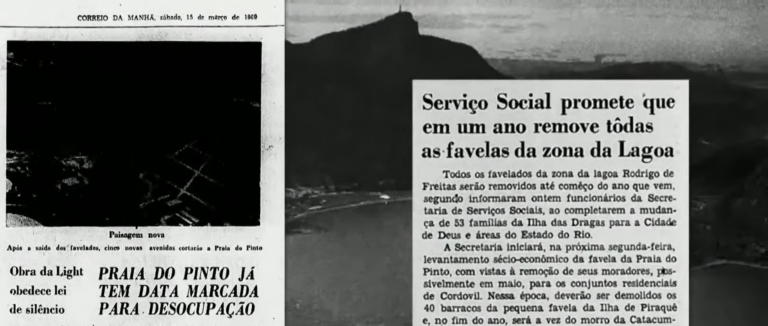

Favelas Forcibly Evicted During the Dictatorship

During the online talk, Marco Pestana, author of The Union of Favela Workers and the Struggle Against the “Negotiated Control” of Carioca Favelas (1954-1964), explained that, while favela evictions in the former state of Guanabara began before the establishment of the military regime, these removals advanced with financial and operational resources during the dictatorship, becoming more frequent and violent.

The central government carried out forced evictions through the Coordination of Social Interest Housing of the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Area (CHISAM). The program, created in 1968, oversaw government bodies such as the Housing Company (COHAB), which built and commercialized housing projects, the Bureau of Social Services, responsible for the removals, and the National Housing Bank (BNH), which financed the program. In practice, the project resulted in the migration of favela residents to areas that were far from the city’s central region and, consequently, far from employment and opportunities.

Pestana explained that “the policy of forcibly removing favelas was not explicitly presented as an attack on the black population. Firstly, because it was portrayed as a benefit that would provide housing—formal housing. Furthermore, it did not single out the black population when mentioning favela residents. The issue [of race] did not come up in official documents about evictions.”

According to Pestana, although race was not associated with the forced evictions of the 1960s, data reveal that racism was clearly present in the process. Pestana reported that, in the 1960 census, 29% of the Guanabara state population was black and brown. In the favelas, however, 61% of the population was black and brown.

As a concrete example of the racial impact of forced evictions, Pestana highlighted the neighborhood of Lagoa, in Rio’s South Zone. This neighborhood, which currently has the fewest Afro-Brazilians in the city, was the site of several favelas 50 years ago. The researcher recalled the favelas of Praia do Pinto, Catacumba, and Ilha das Dragas—predominantly black communities that were evicted from Lagoa during the dictatorship. With this in mind, he explained: “The longevity and depth of impact of this removal policy did not only directly affect those who were relocated, whose lives were destroyed. It also helped reinforce and shape Rio de Janeiro as an economically and racially segregated city. The neighborhood that underwent the most evictions is, today, the least black neighborhood in the city. I think that this is an important element for us to understand the impact [of forced evictions] on the configuration of the city as a whole.”

As a concrete example of the racial impact of forced evictions, Pestana highlighted the neighborhood of Lagoa, in Rio’s South Zone. This neighborhood, which currently has the fewest Afro-Brazilians in the city, was the site of several favelas 50 years ago. The researcher recalled the favelas of Praia do Pinto, Catacumba, and Ilha das Dragas—predominantly black communities that were evicted from Lagoa during the dictatorship. With this in mind, he explained: “The longevity and depth of impact of this removal policy did not only directly affect those who were relocated, whose lives were destroyed. It also helped reinforce and shape Rio de Janeiro as an economically and racially segregated city. The neighborhood that underwent the most evictions is, today, the least black neighborhood in the city. I think that this is an important element for us to understand the impact [of forced evictions] on the configuration of the city as a whole.”

However, the forced eviction of favelas, camouflaged by speeches that emphasized its benefits, did not happen without resistance from their residents. “The largest number of forced evictions took place in Rio de Janeiro from 1963 to 1973. Even with the dictatorship, there was still resistance. [On] many occasions, the population tried to prevent [the expulsions]. But that was not enough: the central government exerted very strong pressure and control over these initiatives.”

Resistance by the Black Movement

With six chapters, the objective of the “Countless” series is to discuss the impacts of the civil-military dictatorship on society, creating a tool that brings together academic and cultural production to amplify the voices of impacted Afro-Brazilians, favela residents, women, indigenous, and LGBTQIAP+ people. The series aims to highlight narratives that are rarely portrayed in mainstream media and in history about the period.

View this post on Instagram

During the livestream, Gabrielle Abreu said that she started thinking about the black population under the dictatorship when she began her degree in history at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in 2014. As soon as she began her studies, she noticed that there was little reference to the Black Movement during the period in traditional education.

“I was soon awakened by the topic of dictatorship and democratization… and in the classes I had about these subjects, I felt the absence of even the slightest reference to the black population in these contexts. It seemed like there weren’t any black people in Brazil during the dictatorship, that the fierce and resistant Black Movement didn’t exist… the black population, at least in the classes I took, was not remembered in any aspect. When we spoke about civil support, when we talked about resistance, nothing [related to the black population] was ever mentioned. This unsettled me: the absence of these narratives didn’t sound coherent to me… I kept asking myself: ‘How could a population that is historically the target of all violence not be affected, to any extent, by a regime known above all for serious human rights violations?’ It seemed to me that some stories weren’t being told.” — Gabrielle Abreu

Abreu stated that, contrary to this absence in the period’s historiography, black people were affected by the dictatorship and many figures of the Black Movement mobilized in resistance to it. “These groups were already resisting by denouncing racism, in a regime that promoted miscegenation and insistently denied the existence of racial discrimination in Brazil. It’s clear that while the dictatorship did not create racial inequalities in Brazil, it in fact propped itself up on racist mechanisms. These already existed to defend a ‘lack’ of racial tension in the country. The interpretation that Brazil was free of racism ended up invading the discourse of black activism, whose whole reason for existing was to denounce racial discrimination.”

Collectively produced, the “Countless” audiovisual series was coordinated and directed by anthropologist José Sérgio Leite Lopes. Additional episodes and livestreams will be released through January 2022. All content is available on the UFRJ Science and Culture Forum’s YouTube channel. This provides an opportunity to learn more about the untold stories of our country: a country that, to this day, insists on letting its memories be forgotten.