This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

Before defining what it means to be a refugee, or why African and indigenous refugees suffer more prejudice in Brazil, we need to discuss what racism is in its multiple versions. In general, in Brazil, non-whites are at the mercy of governments that are historically and structurally racist. Since Brazilian institutions were built through the hegemony of whiteness, everyone that is not euro-descendant is deemed less worthy, oftentimes even in relation to the right to life.

A policy ensuring the basic right to life is a policy that guarantees those public services necessary for survival. If the State is responsible for providing health, education, and safety to all citizens but some groups are denied access to these public services, then the State is selecting who does and who doesn’t deserve quality public health, education, and safety.

It is based on the concepts of necropolitics (by Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe) and biopower (by French philosopher Michael Foucault) that I begin by defining the genesis of racism faced by refugees and African migrants to Brazil—racism that originates from a single extermination policy by the State.

Whether you are Brazilian, indigenous or African, if your physical features are not Western, due to the logic of structural racism, the modus operandi is the same. Therefore, this text is based on the interconnected reality of diasporic anti-racist struggles, and by the struggle for development and the colonial liberation of the African continent.

Institutional Racism and Refugees in Brazil

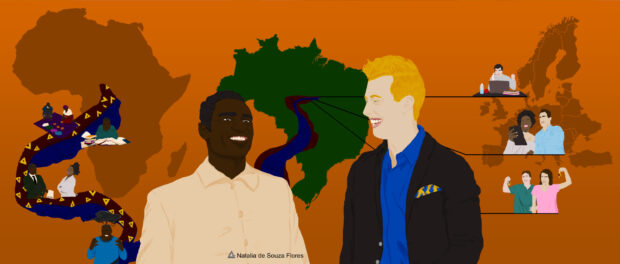

Many refugees move to Brazil with the view that we are a nation receptive to foreigners. But the reality is that institutionalized racism, normalized by society, makes the westernized Brazilian have an ambiguous relationship with black and white foreigners.

Many refugees move to Brazil with the view that we are a nation receptive to foreigners. But the reality is that institutionalized racism, normalized by society, makes the westernized Brazilian have an ambiguous relationship with black and white foreigners.

This happens because, in many cases, the ideology underpinning Brazilian education still dates back to a colonial past that tells the distorted tale of a glorious Global North and a poverty-stricken Global South. This colonizing argument is reflected in Brazilians’ lack of interest in their African and indigenous origins. As a result, the social relationships of immigrants can be compromised based on their racial identities, where one profile is well received while the other suffers xenophobia and other types of violence.

Refugees are different from immigrants. Asylum seekers are forced to leave their country of origin to seek protection as a result of their political convictions, environmental conditions, or religious hatred at home. Meanwhile, those arriving as immigrants in Brazil are usually searching for better opportunities. Pedro Kuassa, a PhD student in Economics at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), explains:

“I am an immigrant and an academic. I have never suffered direct racism in Brazil. But as any black person, I have suffered it indirectly. These episodes are usually characterized by the notorious fear some white people get, when, for example, I am walking in an upscale neighborhood of Niterói. On the sidewalk, right behind someone, I can tell people are afraid of me.”

When refugees try to reach other countries via makeshift boats or by land, it is common for them to encounter a lot of repression, human rights violations, and difficulties in being recognized as citizens. Currently, organized civil society is essential in the defense of socially vulnerable groups’ rights, whether they are Brazilian or foreign. The NGO Cáritas, for instance, provides monetary assistance valued at of R$300 (approximately US$56) per month for refugees, though not quite enough to support them in urban centers like Rio de Janeiro or São Paulo. The contributions of these organizations is insufficient in the absence of public policies to ensure housing, food and employment aimed specifically at migrants and refugees.

Without relatives and friends, most non-white refugees in Brazil live in the suburbs, peripheries, and favelas. They find it very difficult to be hired for regular jobs due to xenophobia, racism, and social class prejudice. In the case of Africans, in particular, it is common to find refugees selling products, clothing, or food in Greater Rio‘s city center. This ends up being one of the few options for the financial maintenance of Africans or indigenous Latinos. Congolese refugee rights activist Chada Kembilu spoke of his community’s experience in Brazil:

“There are many hardships for refugees in Brazil, from getting temporary work papers to securing a job. Especially for us Congolese refugees, who have a very hard time with the Portuguese language, many people offend us telling us to go back home, and leave Brazil for good, but Congo is still at war, and we can’t just go back.”

In Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone, it is common to see Arab refugees with their trades in full swing. Generally, light-skinned refugees find it easier to get regular jobs. Some are language teachers or sell typical foods from their countries in upper-middle-class neighborhoods. In the Brazilian colorist system, an Arab, a Japanese or a Jew can be seen as white, since being white in Brazil is the absence of blackness, more specifically of the Afro-Amerindian being. Thus, Jews or Iberian-Mediterraneans of European descent (such as Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish) have not faced the same difficulties settling in Brazil and are more likely to thrive over time.

African and Indigenous Refugees Living in Favelas and Peripheries

This article investigates the racism that non-white refugees face in the peripheries and favelas of Brazil. From interviews, visits to refugee communities and informal conversations with foreigners, I realized the notorious difficulty they encounter in socializing even in black Brazilian communities, which end up reproducing the same racism that was historically imposed on them.

The first struggle faced by Africans and indigenous peoples, resulting from structural racism, is language: there are very few speakers of African or indigenous languages in Brazil. Despite the practice of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous religions like Candomblé, which use Bantu languages and other native languages in their ceremonies, foreign language teaching is only encouraged for Western dialects—English, French, Spanish, etc. It is rare to find Brazilian students learning African languages such as Kituba, Lingala, Mbochi, Teke, Umbundu, Kimbundu and Swahili; or Afro-Latin-Caribbean languages like Haitian Creole; or even Brazilian or other South American indigenous languages from countries like Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela such as Guarani, Quechua, Aymara, Warao, Pemón, Akawaio, Eñepa/Panare, Galibis or Lanc-patuá.

Institutionalized racism has normalized in the social imaginary that non-European languages are less important than others. The vulnerable situation of the black or non-white individual is enhanced by a discourse that rejects African foreigners, as well as other Latin Americans and Amerindians, and facilitates only the historical heritage of the euro-descendant (or the individual seen as white in Brazil) refugee or immigrant.

This rejection and selectivity were named individual racism by philosopher Silvio de Almeida, and only exist thanks to structural and institutional racism. On the issue of refugees living in favelas and peripheries, it is chronic that the racial violence displayed towards Afro-Brazilian bodies is also easily directed against Congolese, Haitian, Venezuelan, and Colombian bodies, as well as an immense list of other nationalities, ethnicities and skin tones which are rejected by Brazilian racism.

This rejection and selectivity were named individual racism by philosopher Silvio de Almeida, and only exist thanks to structural and institutional racism. On the issue of refugees living in favelas and peripheries, it is chronic that the racial violence displayed towards Afro-Brazilian bodies is also easily directed against Congolese, Haitian, Venezuelan, and Colombian bodies, as well as an immense list of other nationalities, ethnicities and skin tones which are rejected by Brazilian racism.

Therefore, it is a fact that refugees are exposed to an even more vulnerable social relationship than Afro-Brazilians themselves, since in recent years the institutional apparatus meant to suppress xenophobia and racism has been dismantled by the racist structure of Brazilian institutions.

We spoke to journalist Dinho Costa, from Maré de Notícias, a community newspaper from Complexo da Maré, about the presence of refugees in this group of favelas in Rio’s North Zone. He said:

“Refugees suffer a variety of violent acts and end up finding cheap places to live in the favela. They survive together in tiny spaces. Many people say they have body odor. There is a reproduction of racist banter in the treatment given by favela residents to refugees. That’s why they isolate themselves in the Angolan bar, frequented by very few Brazilians.”

This arrogant and inhospitable character perpetuated by Brazil’s colonial heritage in our way of living, has made for a very complex social structure. Brazil was the last major slaveholding country to abolish slavery. Institutionally, from 1539, when the first slave ship arrived in Brazil, until May 13, 1888, the enslavement of Africans and Afro-Brazilians was legal in Brazil. The logic of this perverse colonial system has been maintained in the international relations which Brazil establishes with European countries and the United States. Many observers point to a relationship of continued exploitation, a new neocolonialism, which perpetuates old practices of disrespect and inhumane treatment of all non-white, black and indigenous individuals. To this day, these ethnicities’ professionals are the lowest paid and most exploited, and continuously the most likely victims of human trafficking.

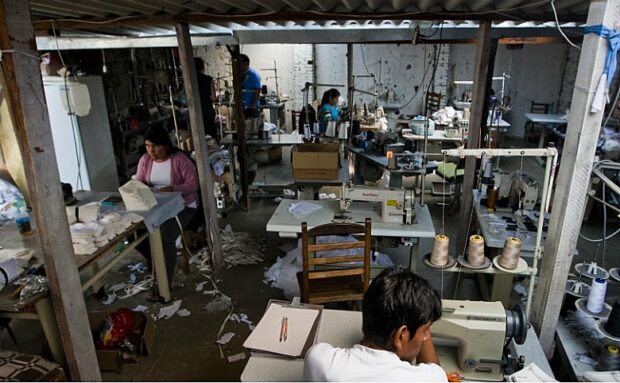

As a living example of Brazilian society’s perpetuation of the colonial structure, there is the issue of refugees being the new slaves of the 21st century. They work isolated on distant farms, construction sites and garment factories; or engaging in illegal logging and mining. Brazilian legislation classifies as work analogous to slavery all forced and unpaid activity, in which the person is prevented from leaving their workplace.

As a living example of Brazilian society’s perpetuation of the colonial structure, there is the issue of refugees being the new slaves of the 21st century. They work isolated on distant farms, construction sites and garment factories; or engaging in illegal logging and mining. Brazilian legislation classifies as work analogous to slavery all forced and unpaid activity, in which the person is prevented from leaving their workplace.

The 2018 Global Slavery Index states that, in 2016, there were 369,000 people living a situation of modern enslavement in Brazil. The research also denounces that the national textile industry is driven by modern slave labor composed, mostly, of refugees and non-white immigrants. Most of these textile centers are located in favelas and peripheries in the state of São Paulo.

With the growing influx of Latin American and African refugees coming to Brazil and finding it difficult to find regular jobs, the Public Labor Prosecutor’s Office created the National Coordination for the Eradication of Slave Labor, which takes complaints about cases regarding the slavery of Brazilians or foreigners. Through complaints made by ordinary citizens, the Brazilian State is pressured to promote policies to socially integrate refugees and end modern slave labor. A manual designed to help recognize and hold accountable those responsible for slave labor has been published.

With the growing influx of Latin American and African refugees coming to Brazil and finding it difficult to find regular jobs, the Public Labor Prosecutor’s Office created the National Coordination for the Eradication of Slave Labor, which takes complaints about cases regarding the slavery of Brazilians or foreigners. Through complaints made by ordinary citizens, the Brazilian State is pressured to promote policies to socially integrate refugees and end modern slave labor. A manual designed to help recognize and hold accountable those responsible for slave labor has been published.

Refugees are closer than we think: many have created communities in the peripheries and favelas. A great place to get to know each other and exchange experiences about racism and barriers to the social integration of refugees in favelas is the Angolans bar, in Complexo da Maré. You hardly ever see any Brazilians in this bar. The Congolese have developed strong communities in Jardim Catarina, São Gonçalo, the largest informal subdivision in Latin America, and in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, mainly in Mesquita and the interior of Nova Iguaçu, where there are African refugees’ irregular occupations and homes.

If public policies don’t even reach the Brazilian peripheral population living in big cities like Rio de Janeiro, how can they assist refugees who face a series of bureaucracies to regularize their status as immigrants in Brazil? There is a large data gap and lack of knowledge of the exact number of African refugees in Brazil. Without specific and reliable data, it is difficult to demand concrete actions from the State to mitigate the social problems faced by refugees. This is unacceptable and alarming.

Finally, the problem of xenophobic racism against refugees and immigrants must be included in the agenda of the Brazilian black movement’s anti-racist struggle. Our agendas of freedom and civil rights are interconnected with the struggle of Africans and indigenous peoples here in Brazil, in the Global South and across the Afro-diasporic countries. Ignoring the refugee issues’ urgency only helps maintain the racist and hierarchical colonial pact that Brazil reproduces in its institutions. In addition, we must defend human rights for all, everywhere, regardless of ethnicity, race, language, sexuality, or religion.

About the author: Emerson Caetano is a resident of Greater Rio’s Nova Iguaçu municipality, a peace activist and founder of NENRI – Center for Black Students of International Relations. A social entrepreneur for racial equality and an international decolonial analyst, Caetano is a UN Fellow of the International Decade for People of African Descent and has experience as a speaker and activist in over nine countries.

About the artist: Born and raised in Rio’s North Zone, Natalia de Souza Flores is a member of Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.