This article is the latest contribution to our reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” It is also part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

In this article, university student Luan Nascimento reflects on how the lack of representation in toys affects black children, and shares his personal account on how this symbolic violence led him to yearn for change, which was materialized through the Boneca Pretta [Blackk Doll] project—founded based on the concerns expressed by his mother, Adriana da Silva Bezerra.

Do you remember your favorite childhood toys? As a black person, such as myself, how many of those female and male dolls looked like you? In Brazil, over half of the population (54%) is black, and yet it’s quite a struggle to find black people represented on TV or in toy stores.

Do you remember your favorite childhood toys? As a black person, such as myself, how many of those female and male dolls looked like you? In Brazil, over half of the population (54%) is black, and yet it’s quite a struggle to find black people represented on TV or in toy stores.

Ten or fifteen years ago, developing black dolls—as a tool capable of building children’s self-esteem and teaching them about the world’s diversity—was not relevant to the national toy industry. But time has passed and, despite the long road ahead, things are changing. Today more than ever, black toys and dolls matter and make a difference in the lives of black people, especially in their early years.

There is a lot of talk about black representation, but few understand the real meaning of this and the effect it has on the process of constructing a black person’s subjectivity. Representation is undoubtedly critical in forming an individual’s identity. However, when it comes to women, people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+, or black people, this right to see yourself represented in the world is constantly denied. Representation is not only important to organizations that fight for rights, but also because it is a part of the social and intellectual formation of an individual who, early on, is presented with the norms, roles, and social spaces reproduced in toys and games.

Therefore, seeing yourself represented or not in each of these spaces constructs subjectivities, personalities, and futures. For example, when a white woman is a successful entrepreneur or when a black woman reaches the highest position in a company where she works, this creates the subjectivity in the female identity that other women can also reach these positions, aside from changing a company’s culture. On the other hand, when television shows cast black actors (which is still an exception), it is most often in roles that are at the service of white people, such as domestic help, drivers, and others. This also feeds the idea that this is where black people belong within society. These social processes (de)educate the population about the social roles and places reserved for black people within this society: with little social prestige and at the service of white people. And with toys, this is no different.

Therefore, seeing yourself represented or not in each of these spaces constructs subjectivities, personalities, and futures. For example, when a white woman is a successful entrepreneur or when a black woman reaches the highest position in a company where she works, this creates the subjectivity in the female identity that other women can also reach these positions, aside from changing a company’s culture. On the other hand, when television shows cast black actors (which is still an exception), it is most often in roles that are at the service of white people, such as domestic help, drivers, and others. This also feeds the idea that this is where black people belong within society. These social processes (de)educate the population about the social roles and places reserved for black people within this society: with little social prestige and at the service of white people. And with toys, this is no different.

We reach the peak of learning during childhood, especially in the early years, a period that starts with birth up to six years of age. Everything is a new discovery. It’s during this time that recognition begins to emerge. Everything that young children come across and everything they have access to becomes a reference point within the construction of their world views, dreams, desires, family models, society, and relationships with others and themselves. Play is an essential activity for the healthy physical and mental development of children. It’s the primary source of discovery and learning during the phase in which the brain most grows within one’s lifetime.

Through play, children create stories, learn about culture, plan their futures, and act out situations they’ve experienced. Toys, as part of this learning process, have long-lasting effects on a child’s education and development. Unfortunately, toys that portray ethnic and familial diversity are rare. A black doll for a black child is potentially a tool for the construction of their identity and a boost to their self-esteem, allowing the child to enter a world in which they are the protagonist. A black doll for a white child is potentially a tool to build affection and intimacy with people from different backgrounds.

For a long time, the beauty standard has been an idealized whiteness, which resulted in an attempt at whitening in order to fit within this “ideal” model. Generations and more generations of black people have tried their hardest to fit within this mold. Hair straightening, surgeries for narrower noses, and even skin lightening procedures, among others, have been seen as ways to insert oneself within the white world.

For a long time, the beauty standard has been an idealized whiteness, which resulted in an attempt at whitening in order to fit within this “ideal” model. Generations and more generations of black people have tried their hardest to fit within this mold. Hair straightening, surgeries for narrower noses, and even skin lightening procedures, among others, have been seen as ways to insert oneself within the white world.

In the absence of black representation, there are many who don’t recognize themselves as black, whitening their own readings of themselves and reproducing behaviors accepted by the white hegemony with the objective of rising up the social ranks.

Where’s Our Doll?

If we live in a world so diverse and rich because of its differences, it makes no sense that we find toys representing only one segment of society. Faced with this scenario, the Where’s Our Doll? campaign was started six years ago in Salvador, Bahia. The initiative by friends Ana Marcilio, Mylene Alves, and Raquel Rocha began during a toy drive for a prison daycare in Bahia’s capital city, after they noticed that the vast majority of the dolls they received were white. The feeling that something had to be done about this persisted, and they went after institutional support through NGO Avante – Education and Social Mobilization. Avante welcomed the project and organized a survey in 2020 also known as Where’s Our Doll? The study showed that the total number of black dolls manufactured by companies declined between 2016 and 2020. According to the survey, the black dolls available on the market accounted for just 7% of the total manufactured in Brazil. In 2020, this number dropped to 6%, even given the increasing attention to racial issues and black representation across the country.

If we live in a world so diverse and rich because of its differences, it makes no sense that we find toys representing only one segment of society. Faced with this scenario, the Where’s Our Doll? campaign was started six years ago in Salvador, Bahia. The initiative by friends Ana Marcilio, Mylene Alves, and Raquel Rocha began during a toy drive for a prison daycare in Bahia’s capital city, after they noticed that the vast majority of the dolls they received were white. The feeling that something had to be done about this persisted, and they went after institutional support through NGO Avante – Education and Social Mobilization. Avante welcomed the project and organized a survey in 2020 also known as Where’s Our Doll? The study showed that the total number of black dolls manufactured by companies declined between 2016 and 2020. According to the survey, the black dolls available on the market accounted for just 7% of the total manufactured in Brazil. In 2020, this number dropped to 6%, even given the increasing attention to racial issues and black representation across the country.

“Dolls are human representations. There is a model and a beauty standard that is constructed and sold to everyone since childhood, and therefore clearly, to a black child, from an early age, when they’re in a store and don’t see themselves on the shelves, they are being violated,” says psychologist Ana Oliva Marcílio, who also participated in the study. She underscored that skin tone and hair color are two extremely strong elements of Brazilian racism and of dolls. Another important point in this discussion, according to Marcílio, is access to these black dolls, which are generally more expensive than white dolls. This makes it difficult for the lower-income population to access them: “Baby dolls are, in general, priced the same. But when dolls portray a woman’s body, there is a difference: black dolls are, as a rule, considered collectibles,” explained Marcílio.

Boneca Pretta [Blackk Doll]

What I’ve outlined so far are my concerns, which are shared by my mom, Adriana da Silva Bezerra. At 48 years of age, she was given her first black doll, but even so the doll was much lighter than her and had straight hair.

What I’ve outlined so far are my concerns, which are shared by my mom, Adriana da Silva Bezerra. At 48 years of age, she was given her first black doll, but even so the doll was much lighter than her and had straight hair.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t even know there were dolls with my color. I had black hair, which was different from the dolls, that had blond hair.” This was what my mom had to say when I asked her if she’d ever seen a black doll when she was a child. When I asked about the effect this lack of representation had on her life, she said, “It’s tough, because they were all blond, right? There was not a single black one like me. Only as an adult did I find out they existed.”

And so I started to ask myself how many adults grew up without even having seen a doll that resembled them. This experience, in my view, contributed to thousands of children, who today are adults, growing up with self-image issues and low self-esteem. Dolls serve as a reference for those who play with them. Unfortunately, a European standard that most Brazilian kids don’t identify with is still dominant. The feeling of not belonging affects their self-esteem and can also manifest in other areas of a black person’s life.

And so I started to ask myself how many adults grew up without even having seen a doll that resembled them. This experience, in my view, contributed to thousands of children, who today are adults, growing up with self-image issues and low self-esteem. Dolls serve as a reference for those who play with them. Unfortunately, a European standard that most Brazilian kids don’t identify with is still dominant. The feeling of not belonging affects their self-esteem and can also manifest in other areas of a black person’s life.

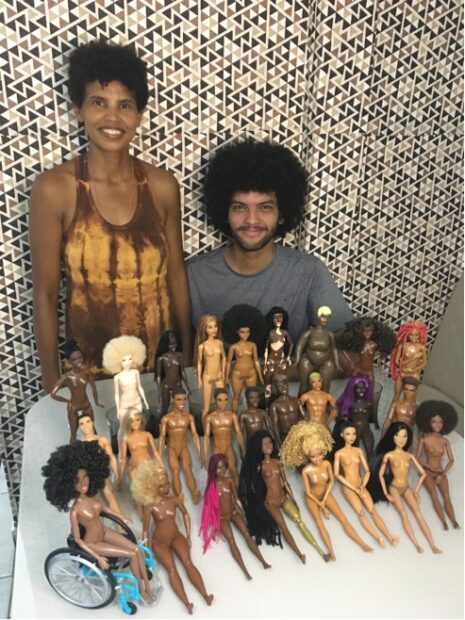

Based on what my mother had to say on the lack of representation and the importance this issue has to us black men and women, in 2017 I created an Instagram account called Boneca Pretta [Blackk Doll], where I currently share posts with pictures of settings with black dolls that include content on education, activism, and mental health.

In 2017, I started customizing black dolls with no intention of creating anything beyond little outfits to post online. The following year, it occurred to me that I could use the dolls to bring up racial issues as well as to invert roles in cartoons, films, and pop culture, creating a black version of everything for which only a white version existed.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

Who’s your favorite princess?

Initially, my mom participated by funding and encouraging the project, but over time and with the production demands, she also started helping me with photographing and filming the things I make and, in some cases, helping me set up the scenery. I work on everything related to the dolls: I have the idea, I research the topic I’ll post about, I produce the dolls including their clothes, accessories and scenery, and I handle the photography for the shoots, edit the photos and videos, and manage the posts.

At first, I just wanted to post pictures of dolls with anti-racist messages and symbols. However, someone got in touch with me through my Instagram profile in 2019, and that was how my first sale of a doll took place. It was then that I realized that I could sell what I made if an interested buyer got in touch. Up until then, I was just posting photos of things that I already wanted to say but didn’t know how.

Beyond just a toy, Boneca Pretta was created to discuss race, racism, blackness, whiteness, and other topics that are dear to black people, in a way that is fun and lighthearted for kids but also for an adult audience, through posts and texts written by myself and by partners on the project’s Instagram profile.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

TAKE RACISM OUT OF YOUR VOCABULARY

Words say a lot about a society’s history and culture.

When expressions such as “mulatto” or “things are black” [signifying, in Brazilian Portuguese, that things are not going well] become natural, it’s a sign of how much oppression and prejudice are incorporated into people’s world views. Between subtleties, jokes and what seem to be compliments, a symbolic violence expands itself as expressions such as these are repeated.

Culture, history, ancestry, music, and the daily life of a black person are just some of the topics covered on Boneca Pretta’s Instagram account. Black representation is one of the ways to combat racism, because when a black child sees themself as a protagonist, this strengthens their self-esteem, helping them believe that they can dream big. On the other hand, a white child will realize from an early age that the world is a diverse place, helping them understand the idea of belonging to the whole and that other phenotypes are as valuable as their own. The discussion on racism must be part of a childhood agenda to the extent that it deeply impacts the process of constructing one’s identity and subjectivities, informing the way in which children will navigate the world and their school lives, as well as how they build relationships with each other.

Culture, history, ancestry, music, and the daily life of a black person are just some of the topics covered on Boneca Pretta’s Instagram account. Black representation is one of the ways to combat racism, because when a black child sees themself as a protagonist, this strengthens their self-esteem, helping them believe that they can dream big. On the other hand, a white child will realize from an early age that the world is a diverse place, helping them understand the idea of belonging to the whole and that other phenotypes are as valuable as their own. The discussion on racism must be part of a childhood agenda to the extent that it deeply impacts the process of constructing one’s identity and subjectivities, informing the way in which children will navigate the world and their school lives, as well as how they build relationships with each other.

A black doll creates an ideal world not just for black children and adults, but also for non-blacks. From princesses who have shaped thousands of girls for years to superheroes who have always been white and idolized, everyone more than ever must get involved in the discussion on the impacts of racism, since it affects all children. There is a tendency to believe that issues of racism only affect black people, a social construct to be problematized. Being raised and educated without being given comprehensive historic, geographic, and sociological information on the black population impacts all children, black and white, since it normalizes an idea about who has or doesn’t have worth, who built or didn’t build history, who should or shouldn’t be respected.

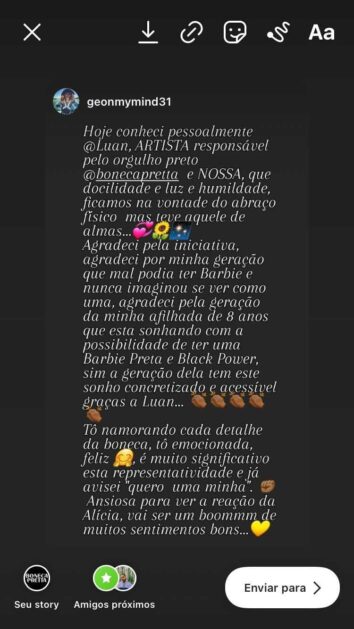

With my involvement on various fronts, I’ve had an extremely positive and encouraging response, which motivates me to continue producing dolls and posting anti-racist content to the account. Mothers send in countless messages thanking me for everything their children have learned through our Instagram account, along with many videos showing children’s reactions as they are presented with their black dolls. The identification is immediate. The joy of being able to recognize yourself in your doll is the best feedback I could hope for. Many black people send in their thanks for being able to finally learn, sometimes together with their kids, about their own culture.

I was motivated by the absence of dolls that looked like my mom during her childhood, and so I wanted to bring this experience to the lives of children and adults. I want to satisfy everyone’s inner child, who can now have a doll in their skin tone or with hair that looks like theirs. Seeing a child recognize themselves in a toy, recognize their hair; seeing white children acknowledge the beauty of black dolls, and seeing black children finally consider themselves attractive and worthy, is priceless. Nothing compares to this.

Below, a little girl named Elis is being gifted her black doll dressed as Wonder Woman, through Boneca Pretta:

Black Representation in Childhood and the Construction of an Anti-Racist Society

We can help transform the racist, sexist, and discriminatory society we live in by promoting awareness towards a more just social environment. In this regard, toys can function as a vehicle of transformation, when we become cognizant of their visual representations and symbolism beyond mere objects of entertainment. By perceiving the world of toys as a microcosm of the adult world, as defended French philosopher and sociologist Roland Barthes, we understand that this miniature world tends to reflect what actually exists in real society.

We can help transform the racist, sexist, and discriminatory society we live in by promoting awareness towards a more just social environment. In this regard, toys can function as a vehicle of transformation, when we become cognizant of their visual representations and symbolism beyond mere objects of entertainment. By perceiving the world of toys as a microcosm of the adult world, as defended French philosopher and sociologist Roland Barthes, we understand that this miniature world tends to reflect what actually exists in real society.

Black dolls construct categories and possibilities of existence for black children who, upon seeing themselves as superheroes, princes and princesses, professionals, etc., understand the places they can occupy in this society, understand how they are seen socially, and even the history of our people in the diaspora.

Although apparently innocuous, toys clearly convey the oppressions that form a society. Children learn from toys and games separately from school. So, if store shelves only have toys of a single color, biotype and hair type available—stimulating stereotypical characteristics of a certain cisheteronormative family structure, of the role of black people and of women—then these will be the models that children will internalize and have in their minds as they grow up. And this will be socially reproduced by these children on their way to adulthood.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

FROM THE QUILOMBO TO WAKANDA

Many people were impressed with the concept of Wakanda in the film Black Panther, in 2018. But what we in Brazil forget is that we had a Wakanda and even our own Black Panther. People of various skills, intellects and social positions came here during European slavery: kings, soldiers, doctors, religious leaders, teachers, philosophers…

They obviously did not accept slavery and joined together to create military bases which were known as quilombos, and that little by little became mini countries with their own languages and cultures, and their own political and social organizations. The most famous of these was Quilombo dos Palmares (or Angola Janga).

Like Wakanda, Angola Janga was surrounded by a forest and impenetrable walls. It was militarily and commercially strong. It was around for over a century, which, as a basis for comparison, is longer than the Soviet Union was around for. It won dozens of wars, a lot more than Brazil has as a country in its history. It had two great leaders: Ganga Zumba and Zumbi—strong, intelligent, shrewd warriors.

Brazil doesn’t have a whole lot of heroes to look up to, but this image is inevitable in Zumbi. He became a legend, music, film; he went down in history in a country that insists in debasing the history of black people.

He is our Black Panther. Actually, it would be fairer to say that Black Panther is the Zumbi of the United States and that Wakanda is Angola Janga’s cartoon version. Angola Janga was more Brazil in 100 years than the whole country has been in 500. And if they had won just one more war, maybe Brazil would be completely different. The Northeast would probably be another country. A country of black empowered people, with no slavery. Or maybe this country does exist in an invisible dome that only Stan Lee was able to access and tell the story under the name of Wakanda.

Text: @abayomi_artes

Boneca Pretta, Cadê Nossa Boneca?, and so many other initiatives like the Periphery Brood Mom and the Alemão Book Club work to transform this reality, to turn this microcosm of the adult world to which children are exposed into a broader field of possibilities and existences. The directional shift towards an antiracist society begins in childhood and with the empowerment of the black people in their conceptions of themselves and what is possible for them to achieve in this country. By creating dolls with dark skin and dreadlocks, dolls portraying black heroes from local culture, orixás [Candomblé deities], dolls with disabilities, and others, it becomes clear that through play, the present can be created while the future is shaped.

About the author: A resident of Morro do INPS in Ilha do Governador, Luan Nascimento is a Library Science major at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He’s been involved in carnival since childhood, parading with the GRES União da Ilha do Governador samba school. In 2018, he interned at the GRES Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel workshop, an experience which led him to create the Boneca Pretta account on Instagram where every week he posts on topics that highlight aspects of Afro-Brazilian culture.

Collaboration: Adriana da Silva Bezerra, a resident of Morro do INPS in Ilha do Governador, has a degree in Nursing and Radiology. Aside from being a member of the Boneca Pretta team, she has a project (as yet unnamed) where she delivers food on a weekly basis to homeless people in the neighborhoods of Ilha do Governador.

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist who works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UFRJ) School of Fine Arts.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.”