This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

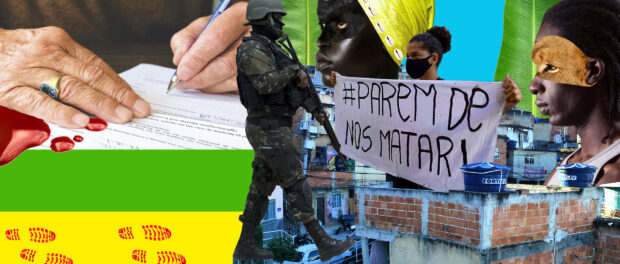

There are over 1,000 favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro that, since their emergence, over 100 years ago, have survived without full rights to citizenship, education, healthcare, permanent housing, culture or memory. It is the favelas and peripheries that most suffer the criminalization of poverty, State neglect, and many other human rights violations, as well as police operations that frequently end in the death of residents and in trauma and mental health disorders for the survivors of these death policies. This is not by chance; after all, the majority of the population that inhabits these territories is black or brown.

Such situations are the result of structural racism, which is when a society structures itself historically based on discrimination that privileges one race to the detriment of another—in this case, white, middle-class privilege to the detriment of black people and favela residents. Some policies are consolidated, new ones are created, and together they result in data that show certain racial groups always departing from a worse position. We all participate in the system, and consequently are benefited or harmed by structural racism. The only way to fight racism is through awareness and by acting in an anti-racist way, or rather, seeking to intentionally unravel and act directly against this system of privileges.

During the coronavirus pandemic, favelas were once again the spaces that suffered most with the impacts of the sanitary crisis. This is another consequence of structural racism, as journalist Glaucia Marinho, researcher and director of Global Justice, pointed out: “In mortality rates, in comparison to the white population, more black people died. Looking at socio-economic data, black people and the favelas suffer more intensely the impacts of the pandemic, because they are the larger contingent among the unemployed. The crucial issue at the start of the pandemic was access to water to wash hands. If we look at the places of residence of black people—peripheries, favelas—water shortages are constant. There was no policy to regularize the access to this fundamental right.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, favelas were once again the spaces that suffered most with the impacts of the sanitary crisis. This is another consequence of structural racism, as journalist Glaucia Marinho, researcher and director of Global Justice, pointed out: “In mortality rates, in comparison to the white population, more black people died. Looking at socio-economic data, black people and the favelas suffer more intensely the impacts of the pandemic, because they are the larger contingent among the unemployed. The crucial issue at the start of the pandemic was access to water to wash hands. If we look at the places of residence of black people—peripheries, favelas—water shortages are constant. There was no policy to regularize the access to this fundamental right.”

Marinho also described how Brazil carries a practice that privileges a white, rich minority in its very structure. In her view, racism is a long-term political plan of the dominant class, carried out through the State, to eliminate and limit the existence of black people, guaranteeing the social reproduction of the white hegemonic system and the maintenance of the power game that favors the white minority over the black majority, which is 54% of the Brazilian population.

The Global Justice researcher goes one step further to say:

The Global Justice researcher goes one step further to say:

“It is important to understand that racism structures our society and is a plan of the Brazilian State to eliminate its black population. There is no other explanation for such violence. Having all these policies [of violence] or the absence of public policies [for basic services] aimed at the black population, [leads us to the understanding that] there is an intentionality, which is that of eliminating, of causing to die, of limiting the existence and the resistance of black people.”

This policy of death, recognized by Brazil’s Black Movement and favelas as a form of necropolitics, is carried out through the militarization of life, the criminalization of poverty and structural racism. It is the favelas that bleed in this racist war on the poor disguised as a war on drugs. It is black, favela youth that are most often murdered by police, and the genocide of the black population goes on unchanged as a public policy by the Brazilian State.

Racism Seen from Maré and the Image of Afro-Brazilians in the Media

To better understand this issue through favela eyes, we heard from residents on the issue of structural racism and what it is like to experience it from inside Rio’s favelas. Biologist Fernanda França, 35, a resident of Vila do João, one of the favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone, brought us a bit of history: “Our country had a long period of slavery. Black people were subjugated and treated like animals. We still have the remnants of this history in our daily lives. We observe situations of racism to this day.”

To better understand this issue through favela eyes, we heard from residents on the issue of structural racism and what it is like to experience it from inside Rio’s favelas. Biologist Fernanda França, 35, a resident of Vila do João, one of the favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in the North Zone, brought us a bit of history: “Our country had a long period of slavery. Black people were subjugated and treated like animals. We still have the remnants of this history in our daily lives. We observe situations of racism to this day.”

França goes on to explain that, “when we think about racism, we think of all the situations of racial prejudice and discrimination on the part of an individual or group against a specific ethnic or racial group. The group discriminated against will typically be socially marginalized.”

Maré is made up of 140,000 residents distributed across 16 favelas, next to the Guanabara Bay. Maré’s first favela was Morro do Timbau, settled in 1940, built and inhabited by workers of the major expressways that surround Maré: Avenida Brasil, Linha Vermelha and Linha Amarela. Maré is made up primarily of Afro-Brazilians and a large number of people who emigrated from Northeast Brazil to the country’s large urban centers during the 20th century, and residents, originally from other favelas, who were forcibly evicted from their homes elsewhere and resettled here.

According to the Maré Population Census, carried out in 2019, 53% of residents identify themselves as brown, and 9% as black. Of the total, 37% of the population self-identifies as white. Speaking about structural racism inside favelas is no easy task, especially considering the enormous stigma established in Brazil over centuries, making it difficult for people to self-identify as black women and men.

According to the Maré Population Census, carried out in 2019, 53% of residents identify themselves as brown, and 9% as black. Of the total, 37% of the population self-identifies as white. Speaking about structural racism inside favelas is no easy task, especially considering the enormous stigma established in Brazil over centuries, making it difficult for people to self-identify as black women and men.

Historically, the image of the black population is also stigmatized by traditional media, which amplifies the idea that this population should remain without due rights. The majority of news stories on television and print media portray black Brazilians as “criminals” and “marginals,” narratives that run counter to the coverage realized with close engagement, effort and dedication by community media outlets, which have been expanding dramatically in favelas. Community media has been playing a critical role in the strengthening and valorization of black, indigenous and Northeastern identities, showing that those relegated to the margins by the State, society and media, are in reality, those who built the nation’s cities. Without the favela, there would be no cities in Brazil.

However, instead of gratitude, respect and rights, favelas experience the criminalization of their territory, culture and residents. This is the product of a history of stigmatization of the favela, in a society that does not even see these places as part of the city. Nonetheless, it is wrong to say that the State is not present in favelas, for, as previously mentioned, it actually makes itself present through police operations, which often end in death, among other violations.

Everyday Racism and How We Can Transform the Debate

According to Lorena Froz, 20, a resident of Maré’s Nova Holanda favela, racism is not just about someone being discriminated against. It is structural, it is much bigger than that. It goes beyond the offenses and so-called jokes that we witness daily. Racism has different configurations and can be realized in different ways. One of them is the lack of access to basic rights. Another example is when a person with black skin enters a shop and is followed around, or when they cannot have a certain type of hairstyle at work.

“[Racism] is a structure that stops people with black skin from having access to universities… from having access to schools, to employment and even from being able to plan their finances due to a lack of space in the job market… That is why I understand [structural racism] as something greater than what we are able to see.” — Lorena Froz

Still according to Froz, we need to talk about racism and anti-racism every day. This is something that needs to be changed in the very structure of society, in a deep and long-lasting way. “Personally, I have never suffered a single act of racism, mainly because my skin isn’t black. But I live in a place that is highly impacted and influenced by environmental and structural racism. I live in Nova Holanda, the favela with Maré’s largest black population. It is no accident that the favela is known by everyone in a pejorative way. My father is a black man and with him, yes, I have witnessed a lot of uncomfortable situations.”

Still according to Froz, we need to talk about racism and anti-racism every day. This is something that needs to be changed in the very structure of society, in a deep and long-lasting way. “Personally, I have never suffered a single act of racism, mainly because my skin isn’t black. But I live in a place that is highly impacted and influenced by environmental and structural racism. I live in Nova Holanda, the favela with Maré’s largest black population. It is no accident that the favela is known by everyone in a pejorative way. My father is a black man and with him, yes, I have witnessed a lot of uncomfortable situations.”

It is important to highlight that pretty much all favelas and peripheries are viewed in a negative way, to a lesser or greater degree, through the criminalization of poverty, of the territory and of blackness. The absence of public policies aimed at these territories also contributes to this criminalization. At the end of the day, black people and favela residents remain increasingly at the mercy of inequality.

Unlike Lorena, França said that she, unfortunately, has suffered and witnessed racism:

“I’ve experienced and witnessed many racist situations, and what makes me notice [them as such] is this process I have of finding out, seeking information, studying non-stop about the topic. It’s always a difficult process because it’s painful… Institutional racism is a collective failure to offer people a specific type of service because of their color. The opportunities [offered] to black people are limited and we call this institutional racism, which exists within structural racism, where, for example, employment opportunities for a black person are minimal. [The lack of] access to quality education is also racism.”

Agreeing with França, Froz concludes that she would explain structural racism to a neighbor quite simply: “Do you know why police enter the favela and kill whoever they find convenient? That’s racism! Do you know why we have trash in our streets and why we only got a high school in Maré recently? That’s racism. Do you know why, when you go to the South Zone of Rio, people stare at you? That’s racism, too.”

It is important that this theme is discussed every day, and in all spaces. Carrying forward racist practices from its pasta, Brazil needs to change and aim its focus on the black population, guaranteeing rights and securing the territories where they live. The country must see the black population and the favela as part of its cities.

“First, we need to listen to what the Black Movement has been saying, has been preparing, proposing and reflecting about Brazil and the possibilities of change. Secondly, we must commit to this real, radical change towards a society that fits everyone. We don’t want one group to be privileged at the detriment of another; we want everyone to have the same rights, above all the right to life, the right to a dignified life.” — Glaucia Marinho

About the authors:

Gizele Martins is a resident of Complexo da Maré, a graduate in Journalism (PUC-Rio) and a master of Education, Culture and Communication in Urban Peripheries (UERJ). She is the author of various books, including Militarization and Censorship: The struggle for freedom of expression in the Maré favela. A community communicator with almost 20 years’ experience, she has received numerous prizes and tributes and is a member of the Maré Mobilization Front and the Palafitas Agency.

Juliana Pinho is a resident of Nova Holanda, one of the favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, and has a degree in both Social Sciences (UFRJ) and Journalism (UCAM). A popular communicator and community organizer, Pinho co-founded the Maré Mobilization Front, is a member of the Palafitas Agency, and is responsible for management and planning of the For Her project. Currently, she manages NGO Fight For Peace‘s portfolio.

About the artist: David Amen was born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, is co-founder and communications producer at the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.