This is the third article in a series of four on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights and is also the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.

You might not know this yet, but if you are Brazilian and, most importantly, part of the country’s low-income, black population, over the past three years, the Black Coalition for Rights was busy influencing the primary political agendas that impact your daily life, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. The organization has been guiding the racial debate in the streets and on social media for the past three years, from within the media to spaces of power, seeking to visibilize Brazilian necropolitics.

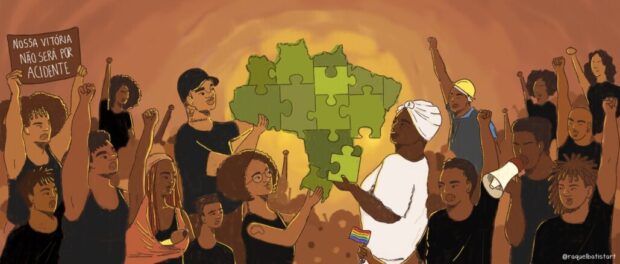

For this reason, throughout the year, we kept up with the Black Coalition for Rights, that currently unites 250 organizations from the Brazilian Black Movement and which, in 2021, consolidated itself as one of the largest social movements in Brazil.

In a country polarized between the left and the far-right—where the far-right won the 2018 elections and reached the presidency—the Black Coalition for Rights emerges as an act of collective and anti-racist resistance in defense of life. Above all, it has risen to fight for a nationwide project that has the face and color of its people. After all, according to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), black men and women account for 56% of the population.

In this political moment, the agreement made by collectives, groups, and organizations that make up the Brazilian Black Movement is a direct response to the election of Jair Bolsonaro, in 2018. Since before his candidacy, Bolsonaro defended withdrawing social rights and affirmative action policies for minorities, including the black population. Despite making up the largest part of the country’s population, black and brown people are under-represented in politics, across all three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial.

“History requires of the Brazilian black population and of the entire African diaspora a coordinated action for the confrontation of racism, genocide and inequalities, injustices and violence derived from this reality. This Coalition comes together to advocate in our own name, from the values of collaboration, ancestry, circularity, the sharing of axé (inherited and transmitted life force), orality, transparency, self-care, solidarity, collectivism, memory, acknowledgement of differences, horizontality, and love. In defense of life, of well-being and of hard-won, inalienable and nonnegotiable rights, we will continue to honor our ancestors, unifying the entire Afro-diasporic population in our struggle for a future free of racism and all oppressions.” — Black Coalition Proposal Letter

The Black Coalition for Rights defines itself as an alliance of Black Movement entities from around the country that advocates in the National Congress and in international forums. With 25 guiding principles, it was already born as a large coalition, with the participation of 100 Black Movement organizations, but grew in numbers in the last two years—from 100 to 250 organizations—besides making great strides in representation and political legitimacy.

From December 1-3, 2021, after nearly two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, groups, collectives, and member organizations gathered at a national meeting titled “As Long As There is Racism, There Will Be No Democracy”—the name of the Black Coalition for Rights’ main manifesto and campaign, launched on June 14, 2020 in the middle of the pandemic.

Produced in hybrid format, in the city of Olinda, state of Pernambuco, the national meeting received leaders of organizations from all over the country and parliamentarians from different political parties to carry out a situational analysis and discuss the agenda of demands, propositions and strategies for the 2022 elections. The meeting had the in-person participation of close to 100 individuals, as well as online streaming for members of organizations and guests.

Ingrid Farias, from the National Network of Anti-Prohibitionist Feminists (RENFABR), stressed the importance of building the emotional aspect of the political process. “Politics is emotional for us. We have a different framework for a different kind of politics. We have a political project for the country.” The Coalition’s strategy includes the expansion of the Black Movement in institutional policy spaces, ensuring representation and representativeness in the Brazilian political agenda.

Ten days before the national meeting, on November 20, Black Awareness Day, the Black Coalition for Rights, in conjunction with the Out With Bolsonaro National Campaign, the Brazilian Popular Front Media Center, the Black Convergence and the People Without Fear Front, unified the traditional Black Awareness March and took to the country’s streets with the motto #OutWithRacistBolsonaro for the 50th anniversary of Black Awareness Day. Since 1971, the date has marked the death of Zumbi dos Palmares, who became a symbol for the search for justice and for the celebration of the life of Afro-Brazilians. In total, 118 marches took place in 110 cities all over Brazil and 10 foreign countries.

Ten days before the national meeting, on November 20, Black Awareness Day, the Black Coalition for Rights, in conjunction with the Out With Bolsonaro National Campaign, the Brazilian Popular Front Media Center, the Black Convergence and the People Without Fear Front, unified the traditional Black Awareness March and took to the country’s streets with the motto #OutWithRacistBolsonaro for the 50th anniversary of Black Awareness Day. Since 1971, the date has marked the death of Zumbi dos Palmares, who became a symbol for the search for justice and for the celebration of the life of Afro-Brazilians. In total, 118 marches took place in 110 cities all over Brazil and 10 foreign countries.

In Rio, the march took place in the streets of Madureira, bringing together activists, trade unions, political parties, Black Movement and favela social organizations, and elected officials. The march interrupted traffic on the main street of the business center, Estrada do Portela.

Babalaô Ivanir dos Santos, 67, a Candomblé priest dedicated to Ifá worship and known for fighting for civil rights, with special attention to religions of African origin, highlighted that fighting racism is essential to alter the economic reality of the black population.

“This [Madureira] is our home and our place of cultural resistance and of perpetuating our identities. This is the location of samba schools Império Serrano and Portela, and of the Serrinha jongo, but, above all, it’s where we have black people working in the informal market as street vendors all along this road we’re traveling on. Interacting with our people is essential to fight fascism, racism, and to change the economic situation, because if we do not confront racism, we will continue to be the main victims of this social and economic crossroads, having to take our livelihood from the streets without having any rights.”

Political Representation Inside and Outside Brazil

The Black Coalition’s tactic is to apply political pressure on the National Congress and the Senate, besides mobilizing and denouncing the Brazilian State to international agencies in Europe and the United States. In October 2021, the Coalition denounced Brazilian structural racism and actions against the black population perpetrated by the Bolsonaro administration in a United States Senate commission, contributing to the commission’s veto of the use of US government funds to remove approximately 800 quilombola families from the territory of Alcântara, state of Maranhão. The Brazilian government was hoping to receive up to R$10 billion (US$1.9 billion) per year from the US to allow the territory to be accessed exclusively by Americans for use in aerospace tests.

Based on this strategy, the Coalition has an active front of advocates abroad participating in hearings and meetings with representatives from the Organization of American States (OAS), the United Nations (UN), and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The Coalition is also linked to the African-American movement Black Lives Matter.

At the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), the Black Coalition had a historical participation with 20 activists, being that it was the Brazilian organization that guided the debate on fighting environmental racism, arguing that “discussing climate justice without fighting racial inequalities is colonialism.”

Brazilian-style Necropolitics

In discussing emergency public policies aimed at facing the health crisis, the Black Coalition for Rights has brought the racial debate to the forefront since the beginning of the pandemic while, at the same time, denouncing the federal government’s genocidal actions. At the end of 2020, the pressure of social movements, including the Coalition’s, made the Ministry of Health include data about race in epidemiological bulletins. The Coalition also demanded an emergency aid payment in the amount of R$600 (US$118).

In Brazil, the accumulation of racism, social inequalities, unequal access to health systems, inadequate housing, and the impossibility of self-isolation, made the black population the nation’s most vulnerable during the pandemic. Other than that, it is primarily the black population that works in occupations directly connected to the food distribution chain and delivery services, among others.

On February 18, 2021, members of the Coalition walked the hallways of the legislative houses in all 26 Brazilian states and the National Congress, demanding that the federal government extend the emergency aid policy until the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, with installments of at least R$600. In the same period, there were acts of protest across the country, demanding that Covid-19 vaccines be guaranteed for everyone through the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS).

As a direct practical action in tackling the pandemic, the Black Coalition launched the “If People are Hungry, Feed Them” campaign mapping, along with other organizations, over 200,000 families living in situations of social vulnerability in formal neighborhoods, favelas, and quilombos in the country’s 27 federal units (states and capital). The distribution of donations is handled through the purchase of food supplies (basket of basic foodstuffs) for a total R$200 (US$38) each.

According to FGV Social (a research center for social policy), almost 28 million people live under the poverty line in Brazil. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic, the number was a little over 23 million.

The campaign was joined by Beyoncé who, through social project BeyGood’s Instagram profile, promoted the campaign with the battle cry: “Brazilian Lives Matter.”

In August 2020, for the first time in Brazilian history, the Black Movement called for the president’s impeachment. Signed by the Black Coalition for Rights, with support from over 600 civil society organizations, the 53rd call for impeachment against President Jair Bolsonaro was filed with the Federal Congress on the day that Brazil reached the mark of 100,000 deaths from Covid-19. A year after the request for impeachment, the number of Covid-19 deaths had multiplied sixfold, reaching 600,000 deaths in October 2021.

In all, according to a survey conducted by Agência Pública, over 1,550 people and 550 organizations have signed petitions for the impeachment of Jair Bolsonaro. 143 documents have been sent to the president of the Chamber of Deputies, with 89 being original requests, 7 amendments and 47 duplicate requests. So far, only seven requests have been dropped or disregarded. The other 136 requests are pending review. Among them is that of the Black Coalition.

The platform “Quilombolas against Racists” listed 55 racist statements made by public authorities between 2019 and 2020. Most of the list is composed of statements made by Bolsonaro and members of his government. In accordance with Law no 7,716/1989, “practicing, inducing or inciting the discrimination or prejudice of race, color, ethnicity, religion or national origin” is a non-bailable crime in Brazil, with a prison sentence of one to three years.

On October 14, the Black Coalition filed for the indictment of Jair Bolsonaro for genocide during the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on the Pandemic. The formal request was not accepted, and the term was left out of the final report published in October. Nonetheless, the Black Genocide Dossier delivered to the CPI contains evidence of how the management of the pandemic was “negligent and criminal.” The brief also denounced how the pandemic was one of the “most effective tools in the process of black genocide currently underway in the country, to which the black Brazilian population is subjected.”

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist and popular communicator at heart. A black feminist, member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she works as a special reporter at RioOnWatch. A fair-skinned black woman, born and raised in a favela, Lima currently lives in Rio’s periphery and is a doctoral student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist who works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UFRJ) School of Fine Arts.

This is the third article in a series of four on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights and is also the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.