This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.

This story, told by writer and former domestic worker Neuza Nascimento, begins in the 1960s in the João Gomes Velho neighborhood of the city of Santos Dumont, located in the interior of the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais.

The first time I felt racism directed at me, I didn’t even know what it was. I must have been around seven or eight years old. We were really short on food, with hardly anything to eat, so I used to fill up on cornmeal and collared greens soup. We ate a lot of persimmons, since we had a tree in the backyard. We didn’t have electricity, running water, or a sewage hookup. We made use of everything we had, we didn’t even produce garbage. In spite of our condition, I didn’t realize that we were poor because there was nothing else to compare it to—until I was eight and went to work in another family’s home.

My job was to take care of a young boy, who was larger than me, while his parents were out working. The father made coconut candy, which I got to taste for the first time only because I scraped the bits off the marble stone that I had to clean. I thought it was strange to take care of such a big boy, but now I realize that he was only bigger and better fed than me, but not older. The arrangement made with my mother was that I wouldn’t do anything but take care of the boy, but in reality I cleaned the house, too. That was where I first saw a real bed, a toilet, a faucet, and other things that were common in any home. Although I cleaned the whole house, I couldn’t move freely through it, much less use the toilet. After I finished cleaning, I could only stay in the kitchen or in the covered backyard that had an outhouse attached, which was what I used. I kept the boy company, but I couldn’t touch him. He said that if I touched him “he’d catch black,” as if it were a contagious disease. What color was this family? White, of course.

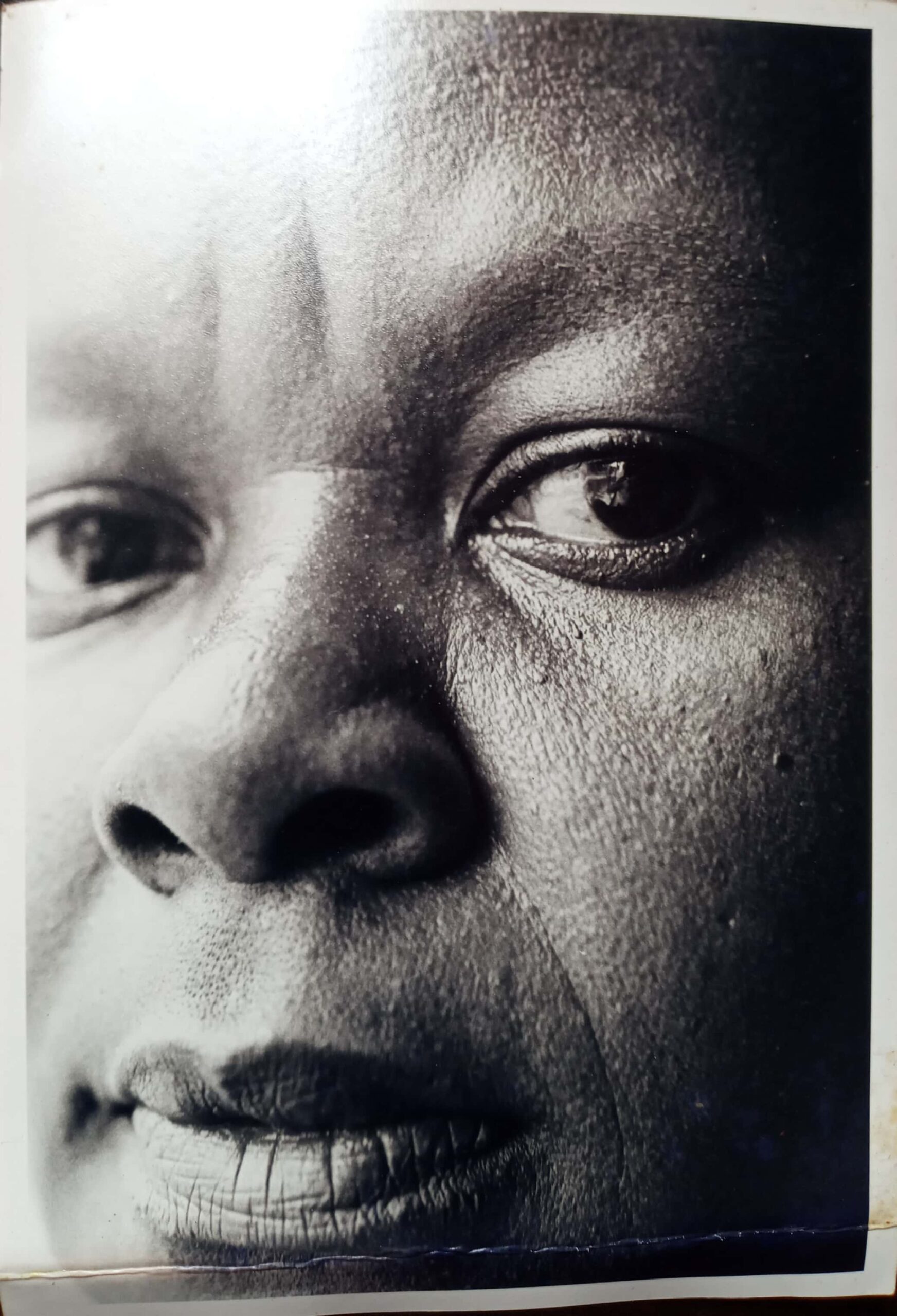

Thinking I was just a regular child, I found out in that house that I was a poor child and thought that I was treated differently for this reason. But it didn’t take long for me to become aware of the color of my skin and to find out that this brought with it inferiority.

Around the time of my first communion, we received a visit from a woman that my mother worked for, washing and ironing her clothes. She came with her daughter, who was around 13, and brought a big package in her arms. Our living room had hardly any furniture; there was a wooden cot with a handmade grass mattress, covered with a simple cloth that we used as a blanket. Besides the cot, we had a china cabinet and a bench for sewing.

When they came in, my mother offered them coffee and invited them to sit down. The girl started to move towards the cot, but her mother shot her a look and she stopped. Then, Dona Rosinha—that was the woman’s name—unwrapped the package and out came a beautiful white dress that she handed to my mother. I had never seen such a beautiful piece of clothing. But when I saw what our visitor did next, I felt something terrible inside of me, a feeling that has taken me years to understand, and which I think I have never gotten over. She took the wrapping paper and spread it out on the bed for them to sit on. I didn’t understand why they did that, but that’s when I lost my innocence —I became conscious of my skin color, of the texture of my hair, of my poverty, and of my insignificance. I felt dirty. Just because I was a different color, because I was of a different race.

My mother washed and ironed clothes for some white women in our neighborhood, and whenever me or my sisters went to deliver the clothes, pick up leftover food, or have any other type of contact with them, my mother would say:

“When you get there, what do you say?”

To which she’d answer herself:

“Yes sir, yes ma’am, no sir, no ma’am.”

For as long as she lived, that’s what she always told us to do.

These instructions followed me around for decades, long after she died, and truly jeopardized my development in all areas of life. And what’s worse, of course my older sisters had the same discourse. Later on, though, I couldn’t really blame her. I think my mother only wanted to protect us.

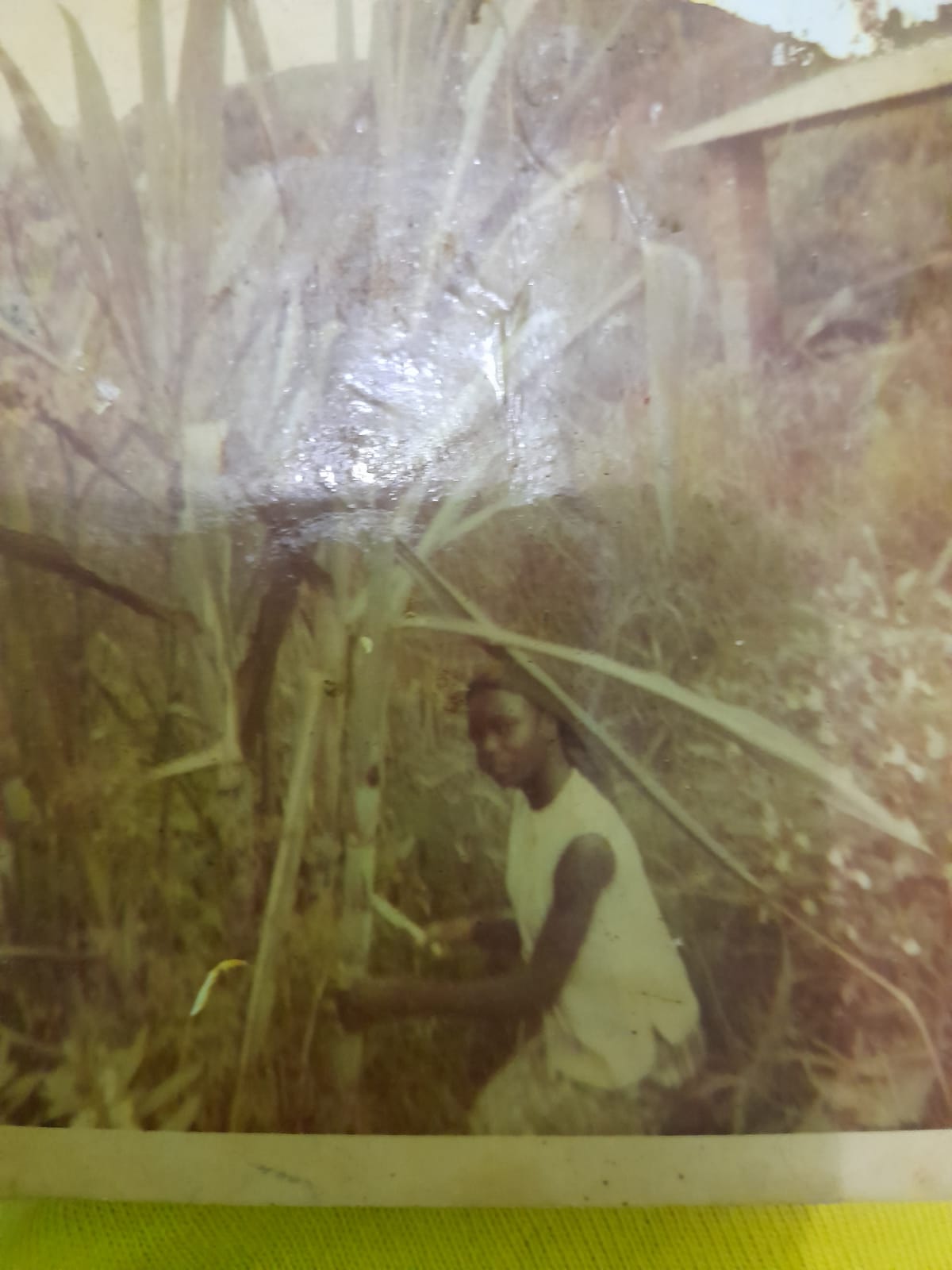

In all the places we lived in Minas, we never owned or rented our home. We always traded work for a place to live. For instance, my father would work the fields for the farmer, and my mother did the domestic work in the farmhouse. Neither of them received a salary for their labor. When they got paid, it was in the form of groceries. The boss had a store, where we’d pick up what we needed for the month. On payday, my father didn’t have anything left as payment. Do I need to point out that the farmers were white?

One day, a couple showed up on our street looking for girls to work, and of course the neighbors brought them to our house, since my mother had so many daughters. They talked about the advantages of letting one of us go with them so we could have a better life; we would study, and my mother would receive a payment every month. Goodhearted, my mother believed them. Under these terms, I went to Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro, and my other sister, whose story I’ll tell later in this text, went to Paraná. Today I recognize this as trafficking of young black girls, but who would think such a thing at the time? My mother only ever thought of what was best for us.

The house in Nova Iguaçu had four rooms. I slept on a cloth on the floor, in a corner of the living room. I did all the housework, except the cooking, and took care of a baby. I didn’t meet anyone the whole time I was there. I’d only leave the house early in the morning to buy bread and come back. The rest of the day, I worked until nighttime. I don’t remember being physically abused, but I was a prisoner. I don’t remember how long I was kept that way. One day, one of my older sisters came to get me.

When I was 11, my older sisters bought a shack in the Cordovil favela and we moved to Rio. It was a dirt-floor shack, with plank walls and a zinc roof. It was the first favela I lived in and there I suffered deep and cruel racism. I was just a child. In the second favela where I lived, Parada de Lucas, it was the same thing, but I could defend myself by then. I understood the situation better.

The residents of Cordovil were mainly from Northeastern Brazil, many from the state of Paraíba. Those who were black didn’t identify themselves as such, they called themselves “morenos” (tanned). They laughed at my braids, called me “little black girl with the skinny legs,” “monkey” and other pejoratives. But that’s racism in the favelas, and that’s another story.

We lived in Cordovil for more or less two years, and soon after that the favela was forcibly evicted and resettled in the neighborhood of Del Castilho. A year or so later, my mother died and one of my older sisters took me to live in the house where she worked, on Joaquim Nabuco Street, in Copacabana.

My sister’s employer, Dona Luiza, embraced me when I arrived. She said that I was cute and that she would raise me as her own child. I was enrolled in the Castelnuovo Municipal School, on Francisco Otaviano Street, which is now a high school. She bought my school supplies and uniform. I was very happy.

On my first day of school, I put on my uniform and, feeling beautiful, headed for the front door to leave. Dona Luiza called after me and told me I had to leave through the back door, the service entrance.

OK. I could forget about being treated as her own child.

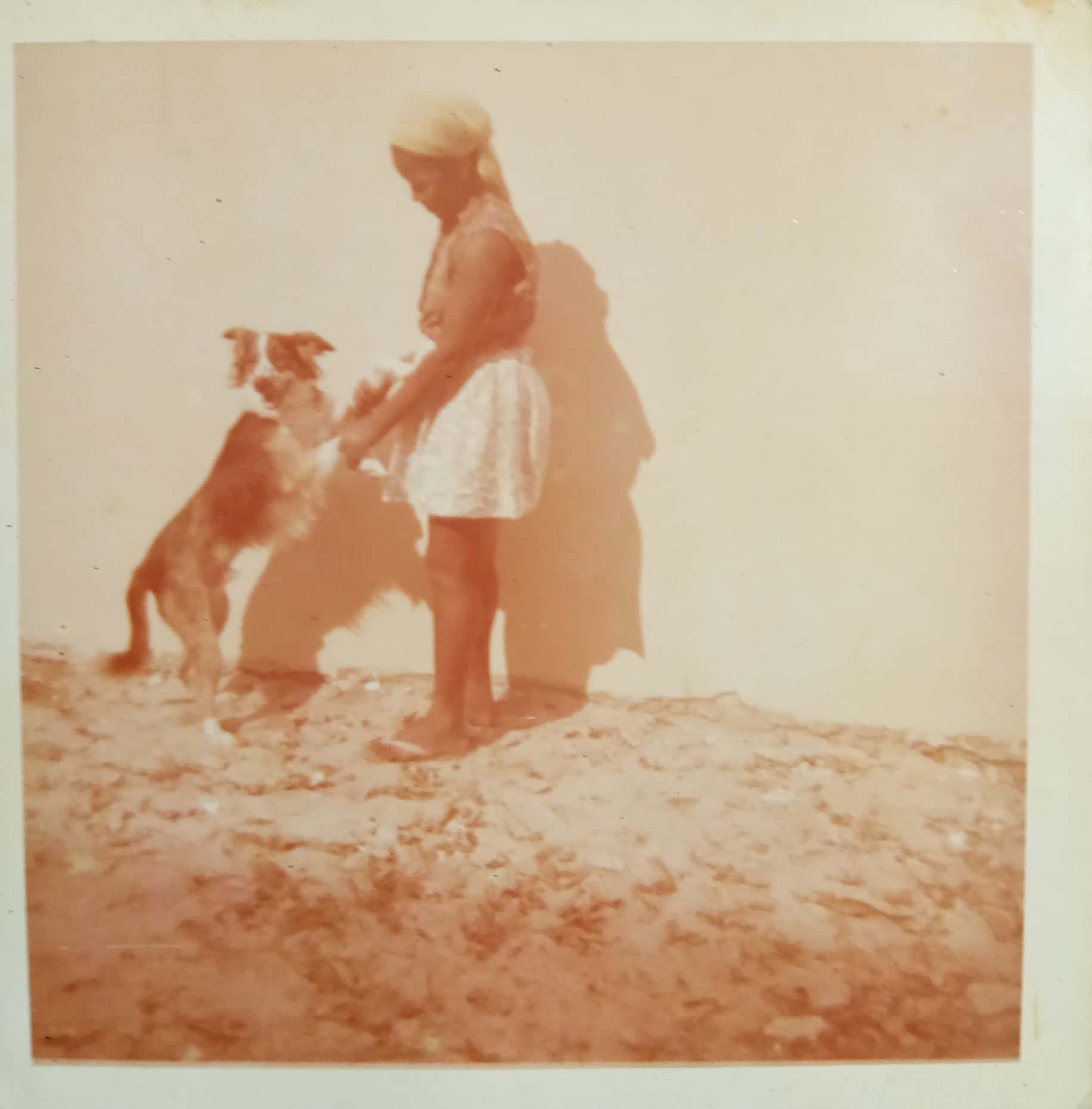

When I got home, I was told I would be working as a cleaner and kitchen aid after school. And so it was. I walked the dog, cleaned the house and served their food. I could only eat after serving dinner, dessert, coffee, and clearing the table. The leftovers. I had to wear a headscarf so that my “rough” hair didn’t show. But I still wasn’t sure if this was because of the color of my skin. My new boss had a boy and a girl in their teens who obviously received treatment completely different from mine. One day, I did something wrong without knowing what, and the boy said, “you little sh**, you black monkey, you should be tied to a tree and beaten!” And from that day on, they decided they would “put me in my place.” I left this house and school when I was 14.

Since I didn’t have any references for any other kind of work, I found another job as a domestic worker.

They were a Lebanese couple, who also lived in Copacabana. I did all the housework and took care of two boys, a six-year-old and a four-year-old. Every night Dona Jeorgete and Seu Aniz went downstairs to play cards with friends and I stayed with the children. The apartment had four rooms and I slept on a sofa in the living room. One night, I woke up with Seu Aniz touching me. I jumped and he grabbed me by the arm, telling me to be quiet; saying that I was going to enjoy being his because, as black as I was, no one was going to want me, and that I should thank him. I said I was going to tell Dona Jeorgete, and he said she would never believe me. I managed to get away from him that time, and other times as well. I wanted to get out of there, but I had nowhere to go. My sisters didn’t know where I was, and I had no days off. One day, I told Dona Jeorgete that I needed to go to school to get a document, and she let me go. When I got to school I went to the office. The headmaster was happy to see me and asked what I had been doing. I told her what had happened and she invited me to work in her home. I didn’t go back to the apartment in Copacabana.

I started a new life, this time in Botafogo. But the way I was treated didn’t change, I was still the little black maid. I couldn’t move through the house freely, except when I was cleaning. One time, I didn’t clean the bathroom walls right, and the woman boss grabbed me by the ear, and after showing me the dirty spot, rubbed my face against it and said, “Clean it right, little black girl!” Because of this episode, there was no celebration on my 15th birthday. When they had visitors, I couldn’t be seen, I don’t know why. At this house, I went back to school and the woman scheduled my housework around my classes. One day, I told her I wanted to take a typing class, that I wanted to be a secretary. She and her husband laughed a lot and offered me a sewing course! Another thing that was different at this house was that I was paid, about half the monthly minimum wage. I left there when I was 16, just turning 17.

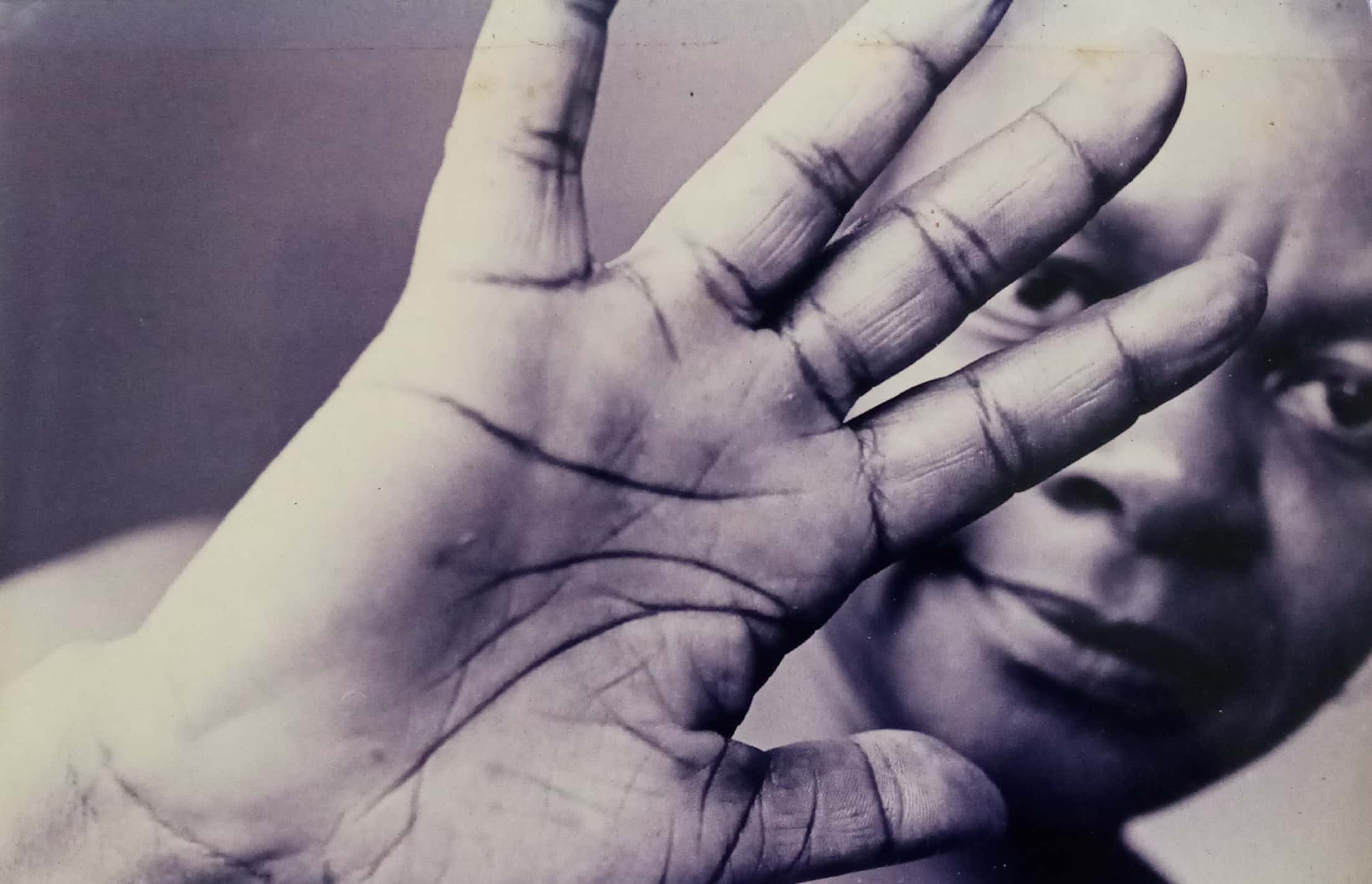

If I were to write here about all the racism, humiliation, shame, sexual abuse, prejudice and perversities that I suffered as a domestic worker and as a person, this would become a book instead of an article. I don’t consider myself a victim, I am a survivor. I was only able to survive because, in all the houses where I worked—and there were a lot of them—my body was there, but my spirit wasn’t.

Don’t think, however, that this covers all the racism I experienced as a domestic worker, there’s more. I worked for a single man, and when I got pregnant, he asked if my child was going to be King Kong or light-skinned. Another boss laughed at me when I asked if I could borrow a book from her bookcase. I also used to clean for a journalist, and one day I wrote a text and asked her to have a look. The following week, I asked what she’d thought and her answer was: “Oh, Neuza, forget it. I didn’t even bother getting past the second line, it was so awful. This isn’t for you, you’re better off as a cleaner; raise your child and forget the idea of being a writer. It’s really not for you, why would you even think that…” I put away the text in a corner of a dresser in the maid’s room and didn’t dare writing again. Three years later, I came across it and discovered that it was an article about defending human rights in the favela. I didn’t feel rage. Instead, I felt deep sadness towards the perversity of human beings.

There was also the time, when I worked for a Jewish family in São Conrado, when I wasn’t allowed near the window at night—I had to stay in my tiny room, with a bed and a small dresser. My food was rice, beans, egg and a banana. Quite often, the egg was rotten. I’d make thousands of meatballs, which my boss counted and separated out for each meal. I wasn’t allowed to eat them.

The sad part is that these aren’t isolated instances, they didn’t happen to me alone. It was the same, and even worse, for my sister, Ana do Nascimento Araújo, since she suffered more and for longer than I did. I don’t really know if these experiences of racism at work affected all of us. After all, we are eight sisters. Most are unable to talk about their childhood and adolescence and say that they never suffered racism while they were domestic workers, or in their lives in general. It’s too heavy to remember, too heavy to talk about. They’re all over 70.

Talking with my 66-year-old sister, Ana, about her journey, she says that racism is mostly veiled these days, and that we have legal defenses against it. But it wasn’t always like that. Ana says:

“I became aware of racism when I was eight years old, when the girls at school didn’t want to take my hand during the games we played at recess. One boy called me ‘Tiziu’ (which is a very dark bird).

Our teacher took our class on outings around the school. Along the way, we had to cross a small bridge which was about two palms wide. I’m afraid of heights, and this teacher, instead of trying to help by holding my hand, as she did for the other children who were white, offered me the tip of her sweater to hold onto. I felt humiliated, like I wasn’t normal.

When I was 11, a couple came around asking our neighbors if anyone knew of any girls to work as domestic help for a family. They pointed at our house and said, ‘The woman over there has a lot of daughters.’ They came to the door and spoke with my mother, who allowed me to go with them, with the attitude that ‘we can’t spoil you, everyone has to work.’ This couple was from [the southern Brazilian state of] Paraná, and no one had any idea where Paraná was. My mother, being a good person, thought that everyone else was good, too. The woman was very nice, and said she would take care of me as if I were her own child, and my mother believed her.

So off I went to Paraná. They had three children. I did all the housework. I waxed the floors of the entire house on my knees, and even though they had a floor polisher, she wouldn’t let me use it; I had to use a brush. I washed the fruit, which the boys counted, but I wasn’t allowed to eat any. She served me my food. At breakfast, I don’t remember what I drank, but she spread yellow lard on my bread instead of margarine. I was supposed to eat it, but when she served me that, I just threw it away. When she made rice casserole, I got regular rice with chicken neck and feet. I didn’t understand any of this, since she had told my mother that she was going to treat me like her daughter, and instead she treated me like a slave. My hair was curly, big and full. When I left home, my mother had braided it and it stayed that way for over a month because I couldn’t brush it on my own. The husband took me to the salon to have my hair done. He took me at night because I had to work during the day and his wife wouldn’t let me go anywhere. My hair looked really pretty, but the girl at the salon said that in order for me not to get sores, I had to put vinegar on my scalp. So I got some vinegar and put it on my head. The wife smelled the vinegar and gave me a hard time because I had used her vinegar. My hairstyle didn’t last more than two days: she took me to another salon and told them to cut my hair off just because I had used her vinegar. I think she was angry because her husband had treated me with humanity. I was only 11.

One day, I spilled oil on the kitchen floor. Since it was nighttime and I was very tired, I left it to clean up the next day. Soon after that, she asked if I had cleaned it up and I said that I was going to do it the next day. She started yelling, ‘This is why I can’t stand black people, I’m allergic to black people.’ She went into the kitchen, and while I was on the floor cleaning, she grabbed me by the hair. Her husband realized what was happening and came after her. He grabbed her arms and said ‘I won’t let you beat her; let’s just take her back the way we brought her.’

Furious, she pointed at me and said to her husband: ‘Even with my arms hurting [because he had grabbed them] I’m going to beat this black girl up!’

Later, she got pregnant and they hired a girl to work with me who got to go home every day. Seeing that I was treated like a slave, she was indignant, and told me to write a letter to my family, telling them everything that was happening to me, and said that she would mail it. I was scared because I was far from home and didn’t know anyone since I never left the house except when they went out and needed me to help with the children. Sometime later, this girl stopped working there and, without me knowing it, wrote a letter to my family.

Just when I had lost all hope that I would ever escape that suffering, one of my sisters showed up to save me. She arrived one morning and I was so happy! The woman boss treated her very well, offering her breakfast, spreading butter on her bread…

My sister took my clothes and put them on the table so the woman could see what we were taking with us, because she had already accused me of being a thief and stealing a pen.

What a marvelous day, when my sister showed up by surprise. It used to be that black domestic workers were treated like slaves, like nobodies. But that’s in the past, today I’m a happy person. The scars are there, but the wounds have healed and I’m here. I can’t remember the face of the girl who helped me, but I will always be grateful to her, wherever I go.”

Someone might ask: “Why put up with all of this?” All the “Yes sir, yes ma’am, no sir, no ma’am?” I, Neuza, didn’t know any better, and was all alone. I thought it was normal, as did my sister Ana.

I’d like to finish this text on a positive note, since not everything is lost. Around 2003 or 2004, I worked in a home as a day worker where I was treated by my boss, Wagner Moura, as a human being and not as a piece of furniture or a kitchen utensil. He called me sister and treated me as one. I knew he was sincere and I’m eternally thankful to him for that.

I am very grateful to be able to tell a bit of my life’s story. It was cathartic, and liberating!

Listen to the Accompanying Podcast in Portuguese Here:

About the author: Neuza Nascimento was born in Santos Dumont, Minas Gerais, is 62 and was a domestic worker for 48 years. Founder and director of community NGO CIACAC, in Parada de Lucas, for 15 years, Neuza Nascimento is a published writer and has one of her short stories in print. Working as a writer, field researcher, and interviewer, she does handicrafts in her spare time. A content creator for website Lupa do Bem, Nascimento currently studies journalism at Universidade Estácio de Sá.

About the artist: Raquel Batista is a visual artist and works as a photographer and illustrator. A black woman, resident of Rio’s West Zone, she is an undergraduate at UFRJ’s School of Fine Arts.

This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.