This is the latest contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

Introduction to the 2021 Edition

2021 was a unique year, including in its headlines. Still reeling from the novelty of the coronavirus pandemic, the world sought to adapt to its consequences as the crisis entered its second year. Unprepared for the devastating effects of an unknown virus and its criminal mismanagement by the government, Brazil saw the return of hunger, poverty, and widespread unemployment in the worst economic crisis of the last 20 years. Amid the echoes of familiar woes, favela residents had a glimmer of hope that their daily lives would be exempted from constant conflict in their territories, a hope kindled by the Brazilian Supreme Court’s August 2020 ruling that suspended police operations in favelas during the pandemic and led to dramatic reductions in violence. This hope was quickly slashed, however, by the police’s blatant disregard to what has become known as the ADPF of the Favelas.

Such events are newsworthy and need to be publicized. It is, however, the way in which they reach the public that continues to be a concern and, once again, the main finding of this yearly column. Tired of a coverage deemed, at times, offensive, inaccurate or plainly false, favela residents have increasingly organized to dispute information production, reclaiming the narrative of their territories and bodies. The growth and empowerment of grassroots journalism is made evident through the recognition of projects such as our very own multiple award-winning Rooting Anti-racism in the Favelas. It is a consensus that a narrative shift is necessary to change reality and influence public policy, making it crucial that information about favelas is designed, produced, and discussed by residents as well as outsiders in dialogue with them. In a context in which public officials systematically choose to maintain these territories and their residents underserved, the role of international media should be increasingly to share favela solutions and raise awareness of the crises favelas have been facing.

The Pandemic in the Favelas According to the Year’s Best International Articles

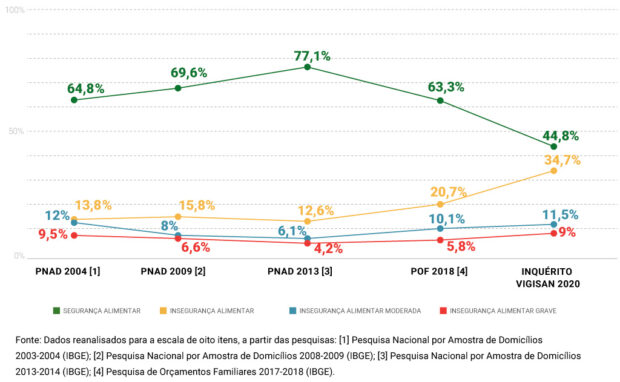

It has never been easy to be a favela resident, but while the economy shut down, government neglect, unemployment, death, and hunger set the tone. The number of daily meals eaten by favela residents dropped from an average of 2.4 in August 2020 to 1.9 in February 2021. ABC News released an article publicizing data from research conducted by the Favela Data Institute, a partnership between the Central Única das Favelas (CUFA), and Instituto Locomotiva highlighting a critical scenario: 68% of favela residents declared they had problems securing food for at least a day, one or two weeks prior to the research.

With staggering inflation, buying power dropped across the spectrum, impacting working-class families more than ever before in this century. In 2021, 71% of favela families lived on half of their pre-pandemic family budgets in territories where 93% of the population have no savings at all. If most favela residents don’t work, they cannot eat in the short term. This impacts greatly on the quantity and quality of food a family consumes.

An article published in Borgen magazine described how it was mostly local NGOs that had to step in to prevent favela residents from starving during the Covid-associated economic shutdown. Three other publications showed how favela urban farming initiatives ensured healthy food on the table for residents: one by Al Jazeera, on a Manguinhos project that established the biggest urban vegetable garden in Latin America, as reported by Reuters, and another by Sproutwired on an organization called Horta Agrofavella, in Heliópolis, São Paulo’s largest favela. All three articles emphasize the resilience and self-reliance of favelas. For the most part, favelas saved themselves from starvation during the coronavirus pandemic.

Although food insecurity has been the norm, with hunger and poverty during Covid-19 traceable to President Bolsonaro’s denialism and inaction, as depicted by a series of articles by the BBC, favelas have held their own. Holding protests screaming the now famous motto “Not from gunshots, Covid, or hunger! Black people want to live!”, favela residents rose up against the federal government blatantly leaving people to fight for their own survival, through self-organization and collective strength. As described by Reuters, many favela residents relied heavily on food parcel donations, with research showing that favelas themselves helped and donated more than the residents of the formal city. In other words: most of the help favela residents got came from their neighbors and other favela residents. This “by us for us” survival strategy reached CGTN in 2021 through the story of community leader Thiago Firmino’s commitment to personally disinfect the alleys and staircases of his community, favela Santa Marta, in Rio’s South Zone.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the government did not produce data specifically about favelas on infection rates, vaccination, or testing. Consequently (not coincidentally) it did not provide the means for effective social distancing or hospital assistance when needed. Nor was correct guidance offered, as NPR put it: the government’s main strategy was a cocktail of unproven drugs.

In 2021, favela initiatives against Bolsonaro’s necropolitical tactics took newsstands globally. The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard*, for example, was mentioned by Reuters and by Global Americans as a community-based solution for the chronic underreporting brought on by government neglect.

With all of this, President Jair Bolsonaro saw his popularity rates drop to the lowest levels since his inauguration on January 1, 2019. By November 2021, his approval ratings had slipped to a record low of 19% while his disapproval levels reached 56% in the same month, as reported by Time magazine and The Brazilian Report.

Quality International Reporting on the Jacarezinho Massacre and Security Policy

The month of May began with what has become known as the deadliest police operation in a favela in all of Rio’s history: the Jacarezinho massacre. Some of the material published about the massacre in international media was well done, detailed and analytical, often offering in-depth personal accounts that sought to denaturalize Brazil’s structural racism and its consequent ingrained racial violence. Such was the case of a Washington Post photojournalistic piece that exposed the violent and illegal pattern of Rio de Janeiro Military Police actions during the massacre. La Prensa Latina portrayed the social acceptance of the inhumanity of deadly police operations, fueled by President Bolsonaro and Rio de Janeiro Governor Cláudio Castro’s full support of police brutality and killings. This option for violence was highlighted by The Guardian as an underlying reason for the ongoing carnage that has been taking the lives of mostly black favela residents. For some, this episode in Jacarezinho was the last straw and, as stated on France 24, sparks an urgent call for change.

In a Guardian podcast, Latin America correspondent Tom Phillips described Jacarezinho as a one-hundred-year-old vibrant Afro-Brazilian community and a historic industrial hub. Visiting the favela the day after the 28 killings, Phillips talked to residents and, giving a detailed account of the massacre, described what he saw as a witch hunt. “Not accused of anything… If you are a young black man, your chance of being shot [out here] is very high.” He traced this widespread violence back 500 years, reflecting the blunt legacy of African and Afro-Brazilians slavery in Brazil. He says that he walked south-to-north, from the river towards the Jacarezinho samba school, talking to locals. The journalist witnessed residents protesting and mourning their loved ones. Some of the dead were adamantly defended by relatives and unrelated residents as innocent, victims of indiscriminate police action. Phillips firmly questioned why alleged criminals were sieged and killed rather than arrested, as the law dictates must be done.

“The official narrative on day one was that police were carrying out an operation to counter the involvement of kids and teenagers in drug gangs. Well, kids and teens have unfortunately been involved in drug gangs for decades. So, quite why it was necessary to do that kind of operation based on that right now, I don’t know… After the police officer was killed in the opening minutes of the operation [at around 6am], some of the police officers began rampaging across this favela: what local activists call ‘operação vingança’ (operation revenge) whereby angry heavily-armed cops decide to go after their drug trafficking targets and local young men that might look like potential drug traffickers in their eyes to kill them.” — Tom Phillips

A very interesting feature of this podcast is that, although it is narrated in English, the audience can hear Portuguese passages by Jacarezinho residents throughout the episode: “ele é de um jornal inglês” (“he’s with an English newspaper”); “não sei quem é não, mas o menino está morto” (“I don’t know who the boy is, but he is dead”), said a woman in a low sad tone; “Não vai papai! Não vai, eles vão te matar!” (“Don’t go, daddy! Don’t go, they’re going to kill you!”), cried a desperate daughter in fear for her father’s life. These lines were not used to further stigmatize favelas. On the contrary, these chunks of reality bring the audience closer to the atmosphere in Jacarezinho during and shortly after the massacre.

Despite a Supreme Court ban ruling out police operations in Rio unless there were required in exceptional circumstances, deadly police operations like this one in Jacarezinho have been killing hundreds if not thousands yearly, as stated in The Guardian. But it was only after Jacarezinho that, as AP reported, Brazil’s top judges decided to review their ban on Rio’s police operations in favelas during the pandemic, making it stricter.

Favela Talents and Creativity Portrayed in the International Media

Amid such crises, favela potentialities, especially with regard to technology, sports, and creativity, also made headlines abroad. Brazil’s Gerando Falcões project, for example, was depicted by Forbes magazine as a possibility to eradicate poverty through smart favelas. The text depicts Edu Lyra, an influential favela leader from São Paulo who is trying to create what he calls a “smart favela.” He wants this high-tech business hub to become a blueprint for the rest of the country’s urban peripheries, and Lyra has been known to succeed against the slimmest of odds.

A number of insightful articles frame favelas as solution hubs to complex and long-standing urban problems. A study by Lund University showed how nature is important to favela residents and how residents seek to preserve it, trying to find solutions to their environmental problems in the absence of government. Wion News prepared a video report on the potential of solar energy production through the example of the solar cooperative, RevoluSolar in the favelas of Babilônia and Chapéu-Mangueira. Considering that the cost of electricity in Rio has grown 105% in the last decade, setting up solar panels is increasingly seen as a way to light up favela homes, as published by Yahoo!.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s ten largest favelas created their own banking system in 2021. A video featured on CGTN America showed the G10 Bank, a favela-based financial institution that offers micro-loans to small business owners and credit and debit cards to favela residents excluded from the traditional banking system. The initiative was covered by AFP and ended up on France 24 and The India Times.

Sports have always been a source of hope for favelas. Soccer player Douglas Luiz said to The Guardian: “I’m proud to be from the favela. I’ve proved we can make it.” A midfielder for English team Aston Villa and hailing from Complexo da Maré’s Nova Holanda community, he talks about what it means to have a favela background, with all the lack of access and opportunities this entails. His message is that dreams can come true for favela residents.

“I’m happy because I’ve proved that we can make it and can achieve our dreams. Clubs have rejected me in the past, I didn’t have the financial means to support myself, but now I’m here.” — Douglas Luiz

Though many, like Douglas, have dreamt of becoming soccer stars, esports have recently proven an unlikely source of hope for young favela residents. As covered by Wired, apart from problems such as exposure to violence, budgetary constraints, hunger, neglect, and social relegation, favela gamers also have issues regarding access to quality devices and Internet connectivity. not to mention very unreliable access to electricity, an endemic problem locally known as an apagão.

“Favela players often play using the Wi-Fi of their friend’s house, always dribbling difficulties.” — Preto Zezé, president of CUFA

Most gamers in Brazil are women and Afro-Brazilians. In this scenario, game design studios have been creating storylines and characters that relate to Brazilian players. The Wired article stated that teams have started to focus on favelas to recruit gamers and that CUFA organizes an annual event, the Favelas Cup, that hosts 12 teams from all over the country to compete in Free Fire, with an audience of over 120,000 people watching the live event.

Originally created as a soccer championship, the Favelas Cup changed its focus amid the pandemic in 2020 toward esports. Free Fire was the chosen game because it is light and runs easily even on older cell phones. It is also the most played game in favelas and the world, with over 150 million daily active users globally. In 2021, some 200,000 gamers on 1,300 teams participated in the Favelas Cup. There’s a cash award and a bootcamp for the winning team.

Já faz aquela call na squad e se prepara que vem aí a CopaFavelas e @afrogamesbr em Vigário Geral!👾🎮

Com muita felicidade, anunciamos que em Dezembro/2021 a Copa das Favelas acontece em Vigário Geral, na sede do AfroGames e dessa vez o final do campeonato será presencial. pic.twitter.com/9ILPPadUtR

— Copa das Favelas: 2021 (@CopaFavelas) June 22, 2021

Make that call and get ready ’cause CopaFavelas and @afrogamesbr are coming to Vigário Geral.

We’re thrilled to announce that the Copa das Favelas will be held in Vigário Geral in December 2021 at the AfroGames HQ and that, this time, the final will be in person.

The Esports Observer featured an article about Rio de Janeiro’s AfroGames, a digital opportunity to address poverty among technology-wired favela youth created by NGO AfroReggae in Vigário Geral, also in Rio’s North Zone. It is the first esport training center located in a favela in the world and is aimed at qualifying young favela professionals for a growing market that, in Brazil, suffers a chronic labor shortage.

Receiving a stipend of around US$200 a month, 100 AfroGames students are learning how to program, play, and speak English to get qualified for well-paid high-tech jobs. During the pandemic, students were able to help provide for their families while doing something they love. Dreaming of becoming celebrity streamers, the AfroGames League of Legends and Fortnite teams are the students’ favorites. This Vigário Geral project also offers physical training and psychological support to help students cope with anxiety, very common among gamers and favela residents.

Favela residents have many reasons to be proud of their talent and creativity. Culture is, by far, the most celebrated favela asset. In the second year of the pandemic, a video by CGNT presented a very special literary Easter celebration for underprivileged children in Complexo do Alemão. The community reading club for children is organized by local Little Star Daycare and Jabuti Prize winner Otávio Junior, raised in the nearby favelas of Complexo da Penha. This club meant salvation for the mental health of many children during the pandemic, especially the ones living in small houses, not going to school, and having limited Internet access.

Favelas also innovated in trying to guarantee typical festivities and celebrations. On our second pandemic Easter, the traditional stagings of the Rocinha Passion of Christ and Via Crucis (also known as Via Dolorosa) could not take the streets with their usual cast of indigenous people and favela residents playing the main roles. But in 2021, members of the “Bando Cultural Favelado” theater company decided to put on a very different Passion of Christ, respecting social distancing rules. From many Rocinha house rooftops, residents and indigenous people from Rio—from the Tupiniquim, Guajajara, and Xukuru peoples—offered safe renditions of biblical narratives. Rocinha residents could watch the show from their windows and terraces while it was also transmitted live on social media. According to an article published by Republic World, this presentation showed religiousness, inventiveness, thriving culture, empathy, and solidarity in Rio’s largest favela.

Another very good article from the AP on favela cultural assets echoes how trap de cria, rap, and funk impact the lives of favela youth. As favela rappers and slammers are always deeply aware of working-class everyday experiences and the nation’s politics, Brazil’s MV Bill was portrayed by Radio Télévision Luxembourg (RTL) not only as a rapper, but as an important political player.

Worst International Reporting on Favelas

The quality of reporting on favelas has improved dramatically over the years, though the use of the term ‘slum’ continues to be pervasive, even in many of the articles described above—a word that does not remotely reflect what favelas are today and which we have been advocating against using to describe favelas for a decade. When we published the first article in this series, in 2013, there was no nuanced, productive reporting on favelas to speak of across the English-language media. Since then, we have seen improvements year by year to the point where this year we have made a decision not to focus this report on the worst media reports on favelas, because they were few, because they were often from low-reach outlets, and so as not to call any more attention to them.

Those we identified included pieces portraying opinions—not facts—shared by police and heavy-handed policy-makers, biased, racist views, criminalized favelas, reinforced stigmas, dishonored human rights, and over-represented negative aspects of favelas. The devaluation of the favela as a community and hub of innovation, culture and solutions also continues to be a feature of the poorer coverage: the stereotypical, clichéd idea that a person will only thrive once they leave the favela persists. There are still articles plagued by the classic saved-by-moving-away fallacy (a version of the white savior complex), implying that favelas are the barrier to realizing potentials rather than the source of such limitations being in neglect and repression by the Brazilian State. Favela residents do not need to be saved. What they need is quality public services, opportunities, equality, support, and having their voices heard.

*The Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard and RioOnWatch are both programs of NGO Catalytic Communities.