Clique aqui para Português

This is the first contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

Throughout the year RioOnWatch monitors coverage of Rio’s favelas in the international press, sharing articles via our RioOnWatch Facebook page and in our monthly news digest. We’re always on hand to support journalists in their coverage of Rio’s favelas, providing information and contacts, and are thrilled when international reports successfully represent and communicate community views and concerns in a nuanced way which reflects the complexity of the situation in Rio today. Though we see an improvement in reporting on favelas generally, there are still many articles which are not only inaccurate but dangerous in reinforcing a stigmatized, unidimensional view of Rio’s favelas and their residents. In a context where rights and services have been historically denied based on prejudice, such reporting can have far-reaching negative consequences.

So to round up 2013, we took a look at some of the poorer reporting on Rio’s favelas in an attempt to show that the story journalists choose to tell and the people they give voice to matters. Images used are those that accompanied the original articles.

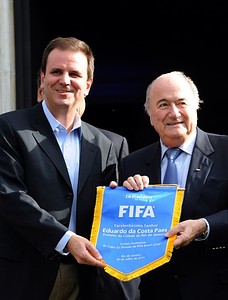

Forbes – Eduardo Paes, Rio de Janeiro Mayor, Reveals Where the Money is Heading to in Brazil: the Favelas

From the headline, you might think this Forbes article of January 2013 is based around a revelation by Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes that large-scale public funds would be invested in Brazil’s favelas. Not so. The article in fact is an advertorial for the favela market and how to enter. First what are favelas? Forbes’ advice: “To have a clear picture of Rio’s favelas, watch one of Brazil’s best movies ever, City of God.” A great movie, there can be no doubt, but since it is a fictional tale based on a housing project between the 1960s and 1980s, it’s hardly a recommended crash course on favelas today.

From the headline, you might think this Forbes article of January 2013 is based around a revelation by Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes that large-scale public funds would be invested in Brazil’s favelas. Not so. The article in fact is an advertorial for the favela market and how to enter. First what are favelas? Forbes’ advice: “To have a clear picture of Rio’s favelas, watch one of Brazil’s best movies ever, City of God.” A great movie, there can be no doubt, but since it is a fictional tale based on a housing project between the 1960s and 1980s, it’s hardly a recommended crash course on favelas today.

But back to Paes. “One of the key people behind the successful installation of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) has been Rio de Janeiro mayor Eduardo Paes.” This is a contentious statement since pacification is a state program and, as the municipal figurehead, Paes has no administrative involvement. Still, we learn he was reelected and gave an “informative” TED talk in early 2012. A talk where he claimed integration of the favelas is part of the solution to Rio’s woes, while that same month illegal evictions spearheaded by his administration were underway.

Moving forward: “The favelas where UPPs have been successfully installed have started to be seen as untapped markets. Favela inhabitants no longer need to get out of the communities to buy goods and services as companies have started to open branches.” The “untapped” market, however, is already largely tapped by local businesses and service-providers. The entrepreneurial spirit which in many ways defines the favelas is absent as residents are cast solely as consumers or laborers. Forbes explains: “Major companies want a slice of that market.”

The article then spends seven paragraphs showing how to go about that, from scholarships and courses to sponsoring community events. Specifically building soccer fields to create long-lasting improvements and transformation is recommended, with Mr. Hutchmacher from Tensport Marketing declaring: “Private companies will be the main actor responsible for this revolution.” But no. As with any revolution, it’ll happen from the bottom-up and herein lies the great irresponsibility of the piece: the lack of recognition that an economy–and agency–already exists in the favelas and that the rules of positive engagement extend beyond sponsoring a football match.

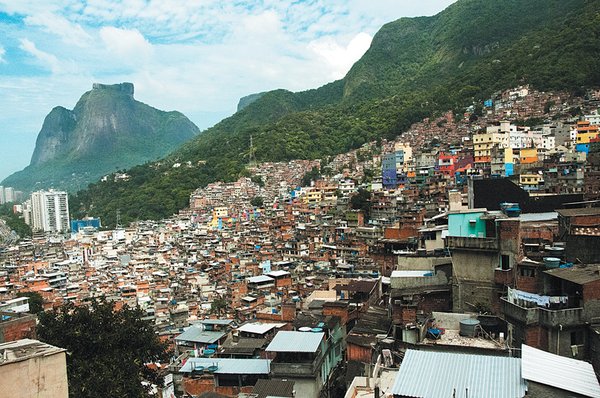

Sunday World – World Cup fans risk their lives if they enter dodgy shanty towns

That a British tabloid published a story full of gaping inaccuracy and falsehood should not be a surprise. This November report from the Sunday World, however, raises the stakes in terms of favela sensationalism. By no means alone in the British press, the paper has created a story out of the threat of potential insecurity during the World Cup and the England team’s hotel’s proximity to Rocinha. “Fans planning to stay in the city have been strongly warned not to venture into the Rocinha favela–where more than 100,000 of Rio’s poorest inhabitants live in almost unbelievable squalor.” Grave misrepresentation here: Rocinha’s residents are nowhere near the poorest in Rio and they don’t live in almost unbelievable squalor. The Sunday World would have done well to fact check as far as Wikipedia. Rocinha has its own real estate brokers, McDonald’s, and some large, beautiful houses, in addition to thousands of local businesses that attract shoppers from outside neighborhoods. But the Sunday World marches on with an expert on Latin American gangs, Rick Garcia, who warns: “People, especially Westerners, who stray into any of the favelas are literally risking their lives.” This despite The Guardian recommending visiting Rio’s favelas, and The New York Times describing how international visitors are increasingly choosing to stay in Rio’s favelas, both explicitly mentioning Rocinha.

That a British tabloid published a story full of gaping inaccuracy and falsehood should not be a surprise. This November report from the Sunday World, however, raises the stakes in terms of favela sensationalism. By no means alone in the British press, the paper has created a story out of the threat of potential insecurity during the World Cup and the England team’s hotel’s proximity to Rocinha. “Fans planning to stay in the city have been strongly warned not to venture into the Rocinha favela–where more than 100,000 of Rio’s poorest inhabitants live in almost unbelievable squalor.” Grave misrepresentation here: Rocinha’s residents are nowhere near the poorest in Rio and they don’t live in almost unbelievable squalor. The Sunday World would have done well to fact check as far as Wikipedia. Rocinha has its own real estate brokers, McDonald’s, and some large, beautiful houses, in addition to thousands of local businesses that attract shoppers from outside neighborhoods. But the Sunday World marches on with an expert on Latin American gangs, Rick Garcia, who warns: “People, especially Westerners, who stray into any of the favelas are literally risking their lives.” This despite The Guardian recommending visiting Rio’s favelas, and The New York Times describing how international visitors are increasingly choosing to stay in Rio’s favelas, both explicitly mentioning Rocinha.

In our research, we have been unable to find any links to Mr. Rick Garcia’s work or credentials. There are, however, millions who can testify to the contrary. Favelas are affordable working-class neighborhoods where people live, work, relax, party, sleep, eat and go about their business. Under certain circumstances and conditions specific favelas at specific times are dangerous places, mainly for their own residents. It is entirely irresponsible to suggest setting foot in any favela, whether in a drug war or not, whether occupied by the police or not, is in serious danger. This enforces the deeply held stigmas around favelas, undermines the great strides made to develop and increase security in these communities, and repels people who would otherwise responsibly visit, support and discover these communities for themselves.

New York Review of Books – In the Violent Favelas of Brazil

Indian born, New York-based writer Suketu Mehti authored the Pulitzer Prize-nominated Maximum City, looking at the underside of Mumbai life. In this August essay for the New York Review of Books he tries his hand at explanatory description of the “violent” favelas of Rio. In fact the title is the first clue to the error Mehti makes in deeming the favelas inherently violent places and the essay goes on to flog the well-worn narrative that favelas are places of drugs, violence and poverty and the UPPs are a salvation. This is done largely through descriptive passages and surface observations which expose the writer’s lack of sensitivity and nuanced understanding of a complex situation. He opens with an anecdote of being almost robbed at gunpoint on the street in São Paulo – which serves as an odd introduction to the subject of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. He then emphasizes the murder and crime rates before performing a sweeping panorama of the situation, relying on inaccuracies and generalizations to uphold the story of unremitting violence.

Indian born, New York-based writer Suketu Mehti authored the Pulitzer Prize-nominated Maximum City, looking at the underside of Mumbai life. In this August essay for the New York Review of Books he tries his hand at explanatory description of the “violent” favelas of Rio. In fact the title is the first clue to the error Mehti makes in deeming the favelas inherently violent places and the essay goes on to flog the well-worn narrative that favelas are places of drugs, violence and poverty and the UPPs are a salvation. This is done largely through descriptive passages and surface observations which expose the writer’s lack of sensitivity and nuanced understanding of a complex situation. He opens with an anecdote of being almost robbed at gunpoint on the street in São Paulo – which serves as an odd introduction to the subject of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. He then emphasizes the murder and crime rates before performing a sweeping panorama of the situation, relying on inaccuracies and generalizations to uphold the story of unremitting violence.

The piece prompted researcher Tucker Landesman to publish a thorough deconstruction in response on FAVELissues, writing: “Mehta’s misrepresentation of Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian culture, and the integration of the favelas through pacification is problematic beyond questions of journalistic integrity and due diligence. First, in Mehta’s essay Brazil is a violent place. Brazilians kill each other left and right, they kill the environment, and they rape their women with seemingly increasing frequency. Favelas are violent drug-fueled places. This type of narrative decouples violence from the many historical social forces that led to current levels of violent crime. This results in the mentality of ‘desperate times call for desperate measures,’ which justifies a form of state repression that would be unthinkable outside of the favelas.”

Landesman articulates the main criticism of this–and all other poor reporting on Rio’s favelas–brilliantly: “Those interested in the remaking of Rio, even essayists writing for foreign intellectual magazines, should think critically and strive to present the facts from the experiences of ordinary people.” The absence of ordinary people’s voices, of local business-owners, community organizers, artists, activists, leaders and others is the major defining feature of bad reporting on Rio’s favelas. By not representing, in any way, the views, hopes and criticisms of those who live in Rio’s favelas, poor reporting perpetuates the story of favelas as negative, violent, impoverished, temporary, passive places where the main actors are state police, drug gangs and big business. The reality, however, is far more interesting and complex, if only journalists would listen to the people who live there.