Favelão—The Voice of Favelados, a newspaper from the 1980s preserves the memory of political communication in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and their resistance against forced evictions.

“Those who live in favelas or working-class neighborhoods in Greater Rio, be very careful not to be fooled once more. Keep your eyes peeled, because certain deputies, councilors, and gubernatorial candidates will show up wanting to take advantage of our impoverished circumstances in order to win votes at our expense. To better recognize these false politicians, let’s denounce what they always promise and never fulfill, what their duties are, what politics is, and how important voting is.” — Editorial ‘Politicians in the Favelas,’ 1st edition, November 1981, from the newspaper Favelão

The text above is an excerpt from a community newspaper. It is part of the news report “Politicians in the Favelas.” Contemporary issues such as the crisis of political representation, the electoral use and manipulation of the vote of the favela population were already present in the text published in November 1981 in the first edition of the newspaper Favelão—The Voice of the Favelados.

The newspaper narrates the memory of favela political communication and shows how, for at least 40 years, favela residents have dealt with electioneering. Favelão was one part of the grassroots communication movement in Rio de Janeiro in the 1980s that caught the attention of historian and journalist Marco Morel.

In 1986, Morel published a book Popular Journalism in Rio’s Favelas, in which he analyzed journalism “built by anonymous hands.” “At first glance, or from a preconditioned perspective, the small newspaper run by favela residents can resemble a poorly made, miniature version of a large newspaper… But it’s good to note: behind these little pages there may very well be, alive and palpitating, the history of a people,” stated Morel.

Favelão was an expression of complex and pluralistic grassroots communication. With 12 pages and a circulation of 3,000 copies, the newspaper was “made by favela residents for favela residents.” It aimed to be a source that represented the “voice” of Rio de Janeiro’s various favelas.

Favelão was an expression of complex and pluralistic grassroots communication. With 12 pages and a circulation of 3,000 copies, the newspaper was “made by favela residents for favela residents.” It aimed to be a source that represented the “voice” of Rio de Janeiro’s various favelas.

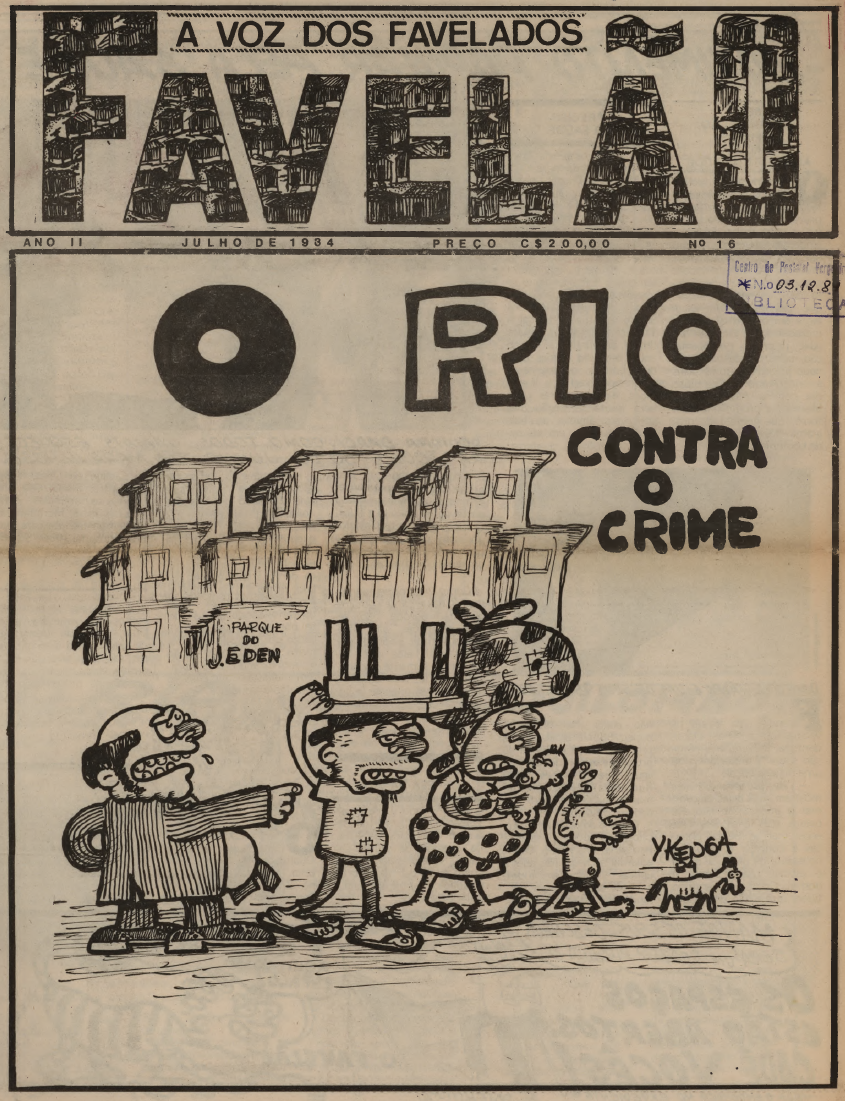

Founded by the Catholic Church’s Favelas Pastoral Committee and community leaders, the newspaper arose from the concrete need to fight against the evictions taking place in Morro do Vidigal in 1978. The resistance of territories and community leaders against attempted evictions in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas was a guiding force of this popular, collective medium of communication, as were the struggle against racism and police violence faced by favela residents.

The newspaper was created by the Favelas Pastoral Committee in November 1981. However, despite the Church’s involvement, all published texts and illustrations were produced exclusively by favela residents.

Due to the legislation of the time, Favelão counted on professional advice from late journalist Gilda Vieira, who was legally responsible for the newspaper. According to illustrator Damião Silva, a member of the newspaper’s team, Vieira provided technical support.

“She did not write the articles, but she helped organize the layout. The articles were written by community residents, those who participated in the vicariate,” stated Silva in his testimony for the study Experiences in Popular Communication in Rio de Janeiro Yesterday and Today: A History of Resistance in Carioca Favelas, carried out by the Piratininga Communication Nucleus (NPC).

The study was inspired by Marco Morel’s mapping of the active journalistic expressions in Rio’s South Zone favelas in the 1980s. Organized by Claudia Santiago, the book outlines 40 such expressions of grassroots journalism in favelas across the North Zone, South Zone, West Zone, Baixada Fluminense, and Niterói, becoming a point of reference in the debate about community-based communication in Rio de Janeiro.

According to the NPC’s research, the height of grassroots communication and education movements in Brazil took place in the context of the so-called “slow, gradual, and safe political opening” at the end of the nation’s military dictatorship, in the second half of the 1970s and early 1980s, with the Favelão newspaper being one of many examples of grassroots organizing in favelas. “During this period, several social movements emerged, mainly organized by the progressive wing of the Catholic Church [tied to the ideals of Liberation Theology] that resisted the authoritarianism and exploitation of the military government,” explains journalist and historian Santiago.

Favelão stood out for having graphic characteristics that differed from the rest of the favela press of the time, which was generally printed on mimeographs. Funded by the Ford Foundation, in partnership with the Archdiocese of Rio, Favelão was a professionally typeset and printed newspaper. Funds reached the newspaper passed on by the Church through the Favelas Pastoral Committee.

The Voice of Favela Residents for the Right to the Favela

Favela residents spearheaded the creation, production, and distribution of the newspaper. The language they used was “extremely avant-garde,” stated Marco Morel. Ahead of their time, the team—amid the military dictatorship—debated subjects regarding national politics, the Black Movement, black culture, gender, as well as favela resistance against forced evictions and the struggle for access to rights such as water, basic sanitation, education, and public transportation.

Favela residents spearheaded the creation, production, and distribution of the newspaper. The language they used was “extremely avant-garde,” stated Marco Morel. Ahead of their time, the team—amid the military dictatorship—debated subjects regarding national politics, the Black Movement, black culture, gender, as well as favela resistance against forced evictions and the struggle for access to rights such as water, basic sanitation, education, and public transportation.

In times of intense political repression, narrative disputes about Rio’s favelas took place through community-based communication. The use of the term “favelado” in the slogan “the voice of the favelados,” for example, demonstrated the newspaper’s strong identity. The meaning and moral weight of the word were being disputed by the newspaper.

At the time, the word “favelado” was already beginning to be used for something other than to describe “one who lives in a favela,” as stated in the Michaelis dictionary. Socially and in the media, it was gaining a discriminatory connotation, used in pejorative and negative situations, expressing the structural racism and social prejudice of Brazilian society.

The aesthetic representation of favelas was also present in the title of the newspaper, which included illustrations of small homes—characteristic of Rio’s favelas—drawn within each letter. The newspaper’s name, according to Silva as stated in an interview with NPC, was chosen in consultation with favela leaders, including Diquinho from Complexo do Alemão.

Between 1981 and 1987, community leaders began distributing Favelão at its symbolically low price or, often, for free to favela residents—from alley to alley, continually under the military dictatorship’s shadow. The idea was to bring access to information to favela residents through the favela itself, without social prejudice and using everyday language.

“For those of you who are holding me, reading me, and maybe wondering ‘what creature is this?’ I would like to give you a few hints. I was born just now and I’m for the favelas, but I’ve been in my mother’s womb for a few months now. My mom is a team of people made up of many favelados, two journalists, and a history student. When I was born, I was so proud to hear that many people were awaiting my arrival. In fact, I knew that I was in the minds of many determined leaders, those guys who are always fighting to improve life in the favelas. Another thing my mom told me was that she wanted me to have a really nice name. So, she went around asking a bunch of people who hold meetings in favelas what my name should be. The name that stuck the most was the one they gave me and before I was even born, people were already calling me Favelão. I admit that I get goosebumps when I hear my friends say my name. Hugs for all of you.” — Editorial “What am I?” 1st edition, November 1981

Favelão‘s grassroots, community-based expression continues, to this day, to be a record of the political action of favela residents—whether through representation, through the historical record of the voices of residents as protagonists of their own narratives, through what it denounced, or through its language. Favelão is a lesson in social engagement through its 26 published editions fighting for the right to the favela.

The claim of the right to the favela can be found in Favelão‘s editorials, eviction news and favela culture. First-person narratives were also common. Some of these stories reveal changes in the landscape of Rio’s favela communities and the way these transformations impacted residents’ daily lives:

The claim of the right to the favela can be found in Favelão‘s editorials, eviction news and favela culture. First-person narratives were also common. Some of these stories reveal changes in the landscape of Rio’s favela communities and the way these transformations impacted residents’ daily lives:

“I came to this favela on July 20, 1937. I went through a lot of hardship. I didn’t have water, I didn’t have electricity, I didn’t have a path. I fought really hard to raise my children. The water was ‘picked up’ on Gustavo Sampaio Street, and a little tram brought it up to us. There were no gas stoves back then, so we had firewood stoves, firewood that we collected on Siqueira Campos Street, at a construction site. I went and gathered it myself. My children studied until the age of 14, because there were no conditions to study. Classes were at night, so they went to a workshop to learn a profession.

I have no complaints about the favela. This is where I fought very hard and made it… I still work, I have bosses who are really good to me. I made it because I had a lot of support and courage. My neighbors are my relatives, I’ve never cried alone. The residents’ association also gave me a lot of support; the association’s presidents always helped me, and I’ve never had problems with any of them. I’m thankful, from the bottom of my heart, to everyone here in the favela where I lived, cried, and loved.”

— ‘My Life in the Favela,’ text by Leopoldina Torquato Farias, 68, resident of Chapéu Mangueira, 2nd edition, November 26, 1981

Fighting for the Brazilian Constituent Assembly and the Right to Breathe

Favelão was set in a time of political effervescence, with various historical forces vying to occupy their space and power in Brazil’s nascent democracy. In this context, where traditional media was highly concentrated, the newspaper loudly demanded the right to housing by fighting for the right to land, demonstrating Favelão‘s broad understanding of territory and housing.

Formed by favela residents who belonged to different political parties (PCB, PDT, PT, among others), the newspaper not only covered elections of the Federation of Favela Associations of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ), but also the country’s political opening. The government even confiscated the newspaper at the print shop twice, under allegations that it was not aligned with the objectives of what should be a favela newspaper.

The newspaper’s official address was Parada de Lucas, in the city’s North Zone, but the team’s meetings rotated from favela to favela. In the second edition’s editorial, the collective nature of how the newspaper was developed was presented. The “boy” who presented the newspaper in every published editorial shared how story ideas were put together:

“To make sure I’m in the loop, every month I have a meeting with my people in a different favela, which is really cool because the residents of that community also start collaborating with us, especially the folks who make newspapers in the favelas. This way, by the time we’re working in a room in Parada de Lucas, there has already been an editorial meeting in Morro do Galo and other meetings are going to happen.” — Excerpt from the editorial ‘They’re talking about me’, published in December 1981

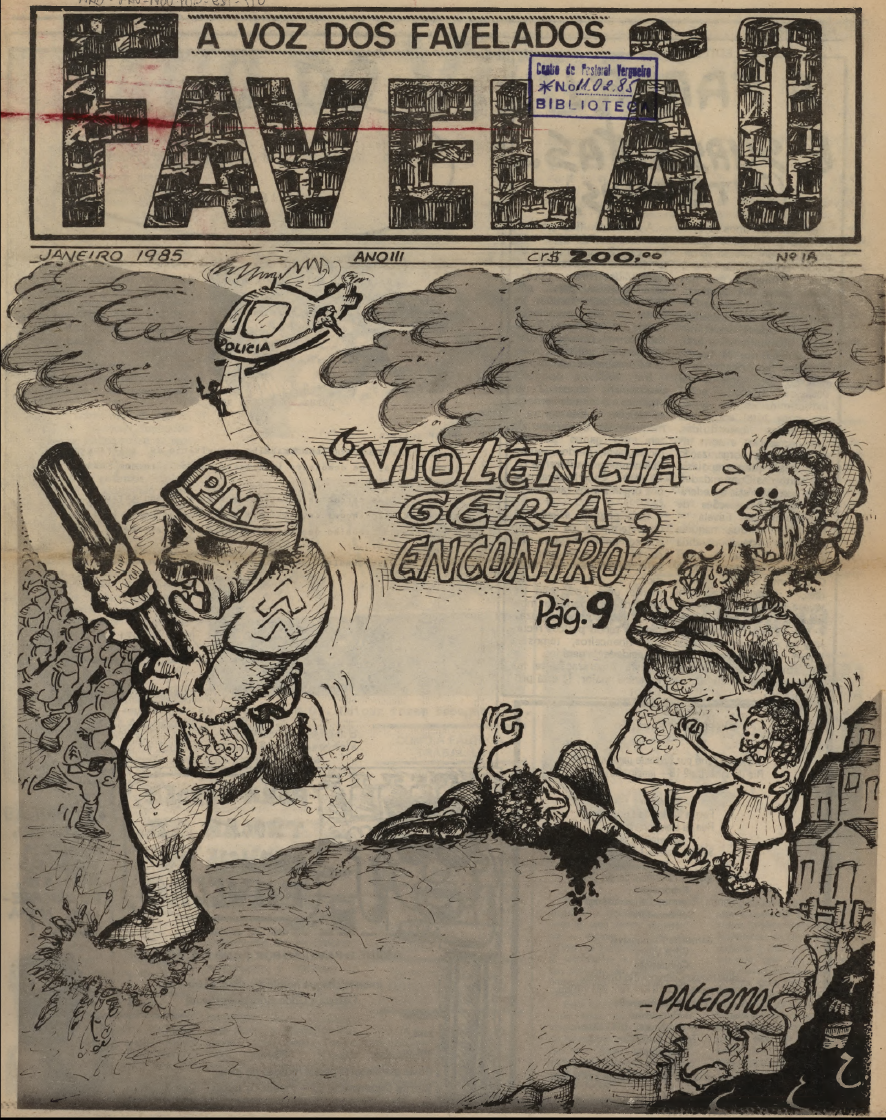

Despite the risks, Favelão also addressed controversial subjects and social taboos. From women’s rights to police brutality, in the form of stories, prose, or explicit denunciations of violence against favela residents from first-person accounts, Favelão guaranteed the right to a voice, citizenship, and political action:

Despite the risks, Favelão also addressed controversial subjects and social taboos. From women’s rights to police brutality, in the form of stories, prose, or explicit denunciations of violence against favela residents from first-person accounts, Favelão guaranteed the right to a voice, citizenship, and political action:

“I’m heading down the favela to go to Leblon. It’s getting warmer and seems like the weather’s going to be nice. I’d love to go to the beach, but I can’t afford to. I have a family to support and I’m the boss. I forgot my ID, but I can’t head back. I’m already pressed for time and the pay is good. Up come the police. Hands on your head, black guy. Take everything out of your pocket and throw it on the floor. Speak little and quietly so I don’t beat you up. We’re the only ones who talk here. First of all, let me see your hand. But I live in the favela and I’m going to Leblon. Ask around, get the right information. Let someone go and get my ID. You already talked too much, shut up, black guy. Soldier, take him and lock him up in the police van. We have a quota to hit because that’s our obligation. Head up the favela and leave without anyone locked up? Not us!” — Excerpt from the short story ‘You’re Suspect’ by Marcão from Vidigal, published in November 1983

According to Célia Fernandes, secretary of the Favelas Pastoral Committee and a participant of the newspaper project as a favela resident, the editorial line was based on the needs of residents. In a testimony for the NPC book, she says: “With those boots of theirs, it was really easy for the police to just kick doors down and go in [to people’s homes]. Because of this, it was in the newspaper that we wrote about what we felt, lived, and suffered through.”

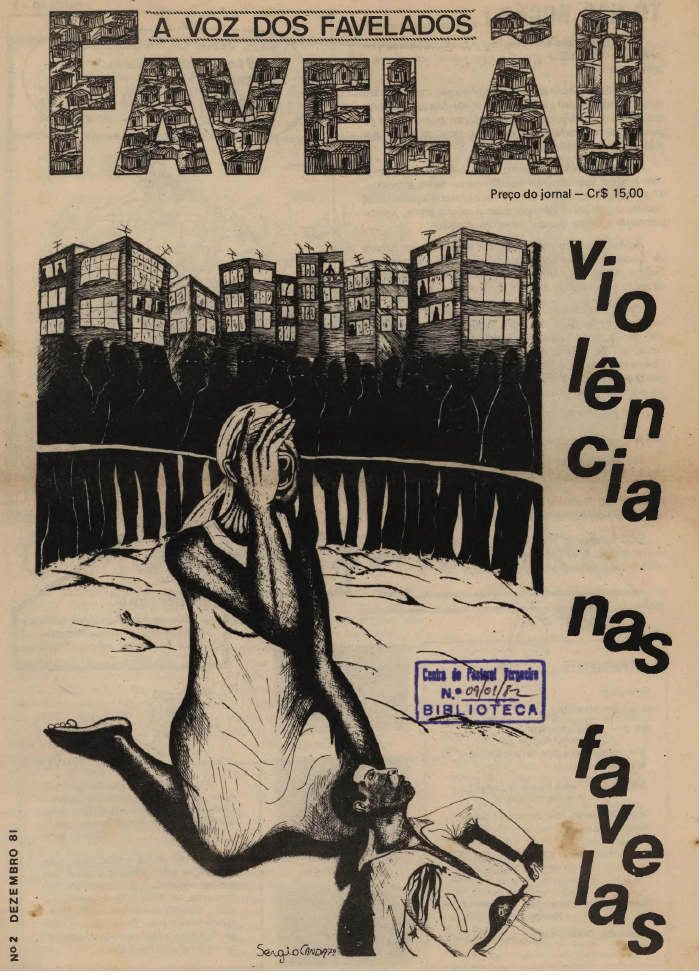

The newspaper has brought forth a historic record on police violence and the genocide against black, favela populations for the past 40 years. The December 1981 issue revealed the repression of the favela’s right to protest against police brutality, and it also shows how State violence is a reality in favelas even within a democratic state:

“Recently, Francisco Gilmar de Souza was senselessly murdered by the police in Rocinha. This dramatic case is one of many: a girl named Marcia was shot while leaving school in Mangueira; Amauri da Conceição was killed by a shotgun bullet in Vidigal. The communities react, but the cases are dismissed. In the case in Vidigal, the boycott of Amauri’s body at the medical examiner’s office forced the favela to form a caravan of buses carrying signs and posters.”

Four decades later, many other men from favelas, like Gilmar and Amauri, have been killed by the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro: Marcus Vinicius in Complexo da Maré, Jonathan Lima in Manguinhos; and Amarildo de Souza in Rocinha are some of their names. Like Marcia, from Mangueira, there have also been other girls killed: Maria Eduarda, killed inside a school in the favela of Acari and Agatha Felix, killed sitting right next to her mother on public transportation in Complexo do Alemão.

Four decades later, many other men from favelas, like Gilmar and Amauri, have been killed by the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro: Marcus Vinicius in Complexo da Maré, Jonathan Lima in Manguinhos; and Amarildo de Souza in Rocinha are some of their names. Like Marcia, from Mangueira, there have also been other girls killed: Maria Eduarda, killed inside a school in the favela of Acari and Agatha Felix, killed sitting right next to her mother on public transportation in Complexo do Alemão.

For 40 years, police in Rio de Janeiro have killed favela residents every day. This includes babies who are still in their mothers’ wombs, which happened in the case of Kathlen Romeu in Complexo do Lins, who was 13 weeks pregnant.

When mother and baby were killed, a survey compiled with data collected from shootout monitoring platform Fogo Cruzado reported that 681 women were shot in the Greater Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region between 2017 and June 2021. In total, 15 women were shot while pregnant; eight of them fatally. Of the ten unborn babies shot in their mothers’ wombs, only one survived.

Fogo Cruzado’s 2021 annual incident report revealed that even with ADPF 635 in full effect—a Supreme Court ruling prohibiting police operations from being carried out during the pandemic unless an exception was made and justified to the Public Prosecutor’s Office—there were 4,653 shootings in the Greater Rio region. Overall, 2,098 people were shot; 1,084 of those shot died and 1,014 were injured. 64% of those 2,098 people (1,342) were shot during police operations in favelas.

The article, “Violence in the Favelas,” published by Favelão portrayed the reality of violence that is still present in favela communities today. The report denounces the State’s oppression of favelas during the military dictatorship. An excerpt from the article states: “Social injustice recently killed Gilmar. How many must die for people to have the right to justice?”

The question above was asked anonymously by a favela resident through the newspaper. Shockingly, the same question asked in Favelão over 40 years ago was asked by late councilwoman Marielle Franco on Twitter one day before she was murdered:

Mais um homicídio de um jovem que pode estar entrando para a conta da PM. Matheus Melo estava saindo da igreja. Quantos mais vão precisar morrer para que essa guerra acabe?

— Marielle Franco (@mariellefranco) March 13, 2018

Another murder of a young man entering the Military Police’s death count. Matheus Melo was leaving church. How many more need to die for this war to end?

The Keeper of Memory and Register of Social Facts from Favelas

In general, printed newspapers are the holders of official memory. They capture important social moments from specific time periods; this is another reason why printed newspapers from favelas are important.

The NPC study Experiences in Popular Communication in Rio de Janeiro Yesterday and Today: A History of Resistance in Carioca Favelas and its data collection sparked a concern for maintaining the memory of community-based communication in favelas. Simply finding old editions of Favelão seemed to be almost as impossible as maintaining the circulation of favela-based printed newspapers  today.

today.

For example, the Brazilian Press Association (ABI) and the Rio de Janeiro City Archive keep one or three copies of Favelão and other favela-based newspapers. In the case of Favelão, not even the Favelas Pastoral Committee still had the archives available. This is because in 2003, the entire archive of the newspaper was lost when several pastoral fronts of the Archdiocese of Rio were dismantled. It was only possible to access digital copies of Favelão through the Vergueiro Center of Documentation and Research (CPV); almost every edition of the newspaper can be accessed through the Center.

With over 70,000 pages of digitized documents, the collection is a strategic act to preserve the memory of workers’ activism in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, community-produced newspapers, the grassroots social movements in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, and the Black Movement.

The newspaper played a crucial role in denouncing racism in the 1980s and demonstrating how the military dictatorship treated favelas. According to Fernandes, one of the most impactful stories was published in October 1982. In the article, the newspaper published a photo taken by Luiz Morier, originally published in Jornal do Brasil in September 1982 with the caption: “The men were led to the police tank like enslaved people.”

The Jornal do Brasil publication sparked outrage and Favelão reacted by publishing the article “In 1888, 1982 They Want Black People in the Kitchen.” The title is a reference to the liberation of enslaved people in Brazil in 1888 and discussed Brazil’s supposed racial democracy in 1982, with 94 years separating the abolition of slavery and the photo published in Jornal do Brasil. For Fernandes, creating that edition was an incredible act of courage.

“It wasn’t easy to speak about police violence, or any type of violence in the favela. You had to really put yourself out there. We were afraid, yes, but we dreamed of freedom.” — Célia Fernandes

Favelão is Still Here, But Different

While Favelão continues to exist in printed form, according to information from the Rio de Janeiro Almanac of Union and Grassroots Communication, the original project—with active participation, centered on favela residents—came to an end after the 26th edition, in 1986.

While Favelão continues to exist in printed form, according to information from the Rio de Janeiro Almanac of Union and Grassroots Communication, the original project—with active participation, centered on favela residents—came to an end after the 26th edition, in 1986.

This was largely due to the end of funding from the Ford Foundation, in addition to changes in the newspaper’s editorial guidelines. “The exact number of print runs of Favelão is unknown,” according to information from the NPC study conducted in 2021.

The last issue of Favelão that we had access to was in November 2015. The newspaper was published in four pages—an A3-sized piece of paper folded down the middle—and was very irregularly distributed.