It’s been over five weeks since journalist Dom Phillips and indigenous expert Bruno Pereira disappeared in the Javari Valley, in the state of Amazonas in northern Brazil.

Bruno Pereira worked in the highest ranks of the National Indian Foundation (Funai). Above all, his knowledge and way of working were recognized by the indigenous peoples with whom he worked. In 2019, after President Jair Bolsonaro came to power, Pereira was downgraded from his leadership role at the agency for acting against illegal mining in the Amazon. As working for the institution became more difficult, Pereira asked to leave his post to better serve the interests of indigenous peoples. He then became an advisor to the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (Unijava), a region located in western Amazonas, close to Brazil’s borders with Peru and Colombia.

Journalist Dom Phillips was one of Pereira’s working partners. More than just a contributor to The Guardian reporting on Brazil, Phillips chose the country as his home. The journalist married Alessandra Sampaio, a Brazilian, and had resided in the country for about 15 years. Phillips covered topics related to the environment, mainly focusing on the Amazon and its peoples. He wrote dozens of articles on the Amazon biome, the advancement of deforestation and its illegalities, becoming one of the main voices contributing to the international coverage of the Amazon region.

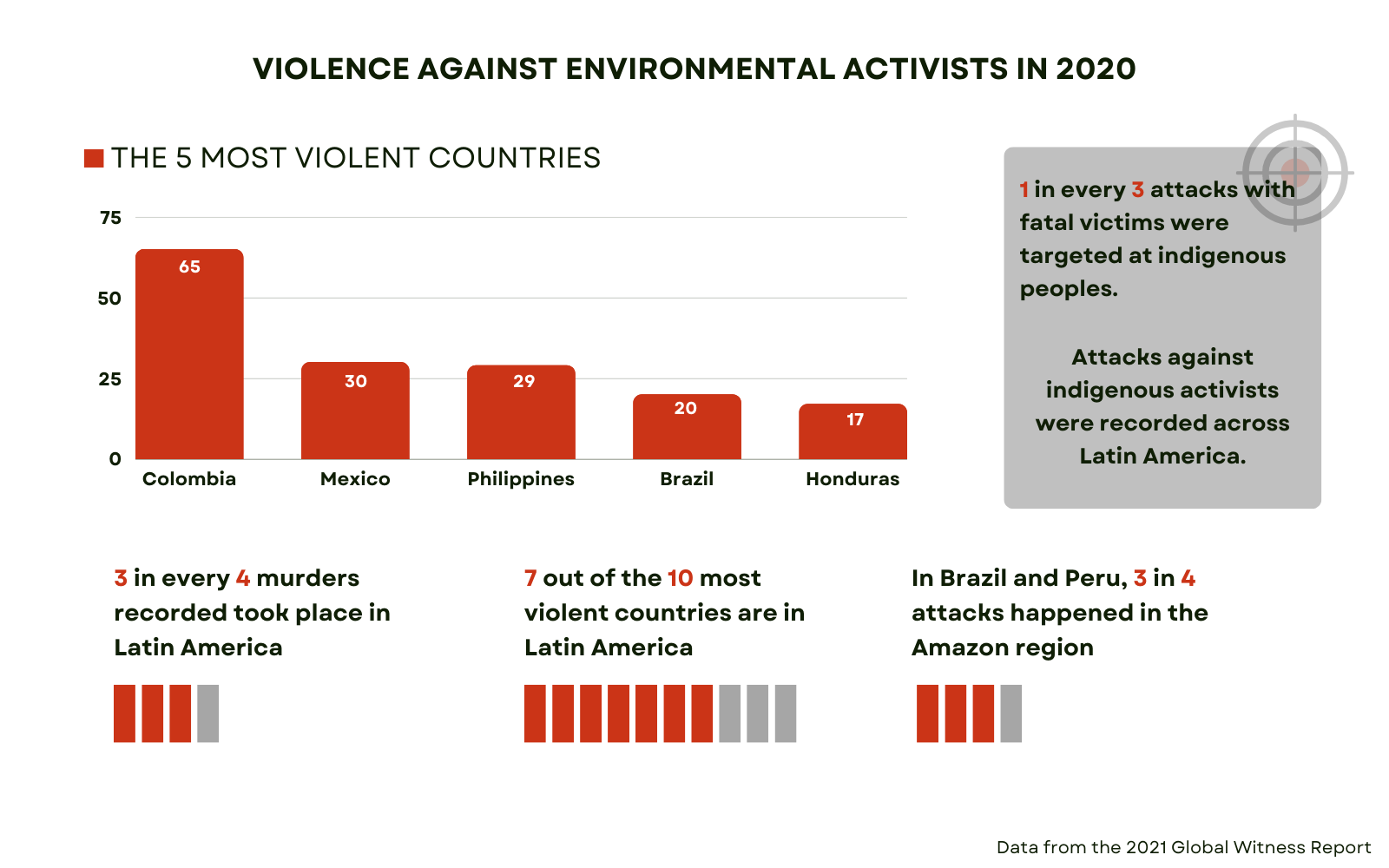

Their brutal murders are not an isolated case: the persecution of environmentalists, journalists and social activists is a growing reality in Brazil. According to a survey by Global Witness, 20 people lost their lives in 2020 as a result of the struggle for land and the environment. Brazil ranks fourth in the number of deaths of environmentalists and land rights activists, behind Colombia, Mexico, and the Philippines. This targeted violence is a consequence of the policy at play, which dismantles the public bodies responsible for protecting environmental reserves and the lives of forest peoples. Reporting what happens—whether in the form of filing a complaint, protesting, or writing—makes environmentalists, activists and reporters vulnerable.

Fighting for Rights in Brazil: A Crime Yielding the Death Penalty?

Everywhere you look, the situation of those who fight for social and environmental rights in Brazil is worrisome. The same applies to those who try to echo these demands as a reporter. According to the organization Reporters Without Borders, over the last decade, Brazil has become the second deadliest nation for journalists in the Americas, with those working in small and medium-sized cities covering corruption and local politics the most vulnerable.

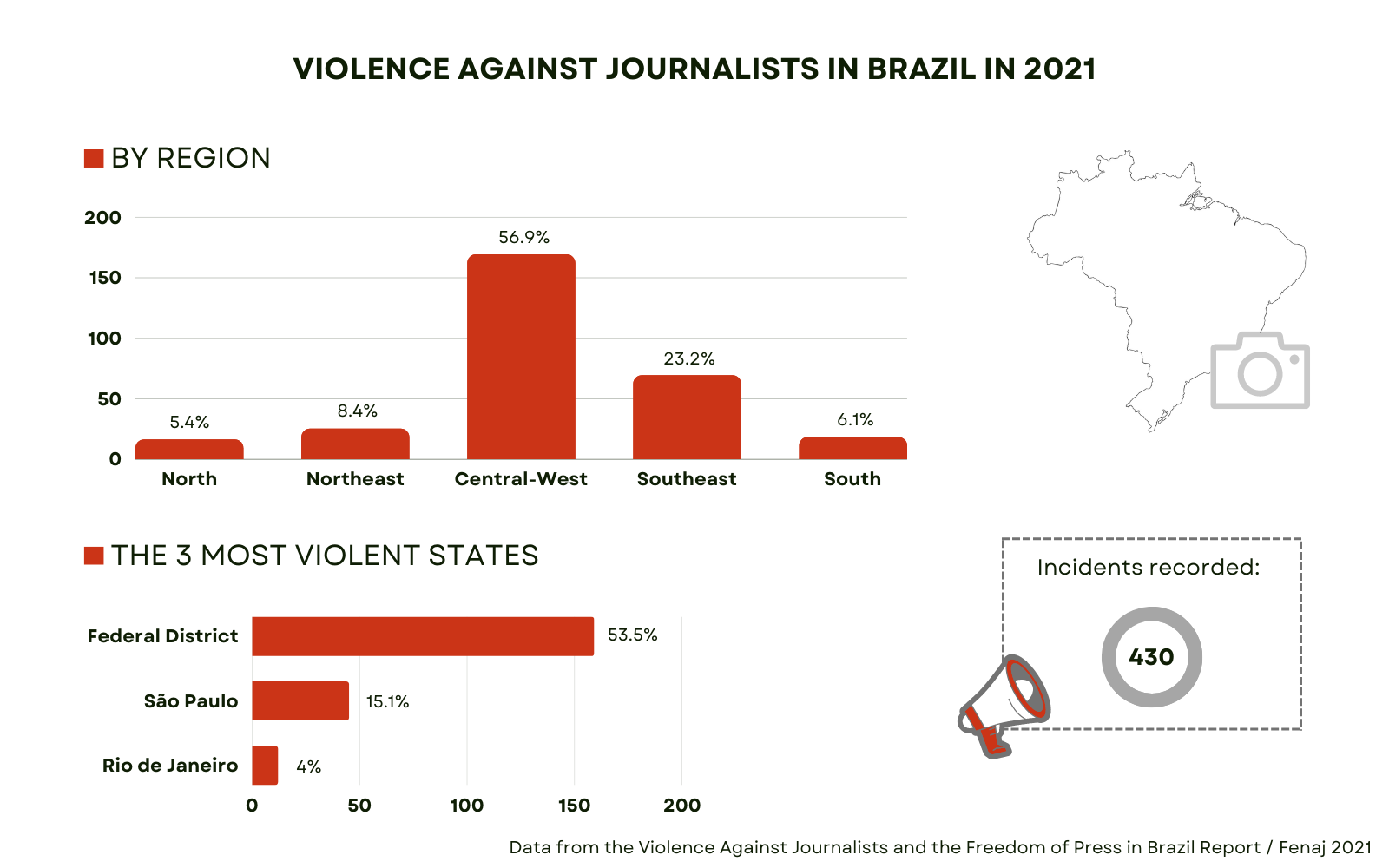

Attacks on the freedom of press in Brazil are monitored by the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj), which publishes an annual report. In 2020, its survey, which has been carried out since the 1990s, broke a record with 428 incidents infringing on the freedom of press. Its most recent report broke its own record with 430 attacks on media professionals in 2021. The Central-West part of the country appears to be the most violent region for journalists, with the region housing Brasília, seat of the federal government, in first place.

Being a (media)activist in Brazil has always been a difficult task, but several studies highlight that the rise of Jair Bolsonaro’s government has only intensified this scenario. The Global Expression Report, compiled by the NGO Article 19, reveals that Brazil dropped 18 spots in the freedom of expression rankings in just one year. This is the most significant drop recorded in the past ten years. Among the 161 monitored nations, Brazil is ranked 94th, behind all other Latin American countries, except for Venezuela.

Article 19 also underscored the fact that, upon taking office in 2019, Bolsonaro introduced two projects that could significantly undermine the guarantee of freedom: the first would allow for controlling civic spaces and reducing freedom of expression; the second would increase the number of public officials authorized to classify public documents and information as confidential for up to 50 years. After strong public pressure, both projects were withdrawn, but they served as clear examples of where the Bolsonaro government stands on these issues.

The same report also points out that, among journalists, women were the main targets of attacks. In July 2020, Article 19, along with other organizations, denounced the government at the 44th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council. From the beginning of his term until that moment, Bolsonaro and his appointed ministers had already attacked women media professionals at least 54 times. Overall, between January 2019 and August 2020, the president made 440 statements or attacks against journalists or reporters. According to the survey, Bolsonaro is the main aggressor towards media professionals.

The Struggling Lives report, organized by the Brazilian Committee of Human Rights Defenders (CBDDH), is another study that demonstrates how the country’s current executive branch has deepened the criminalization of and reinforced violations against social activists. For example, in the environmental space, this was visible in the changes made to the structure of the National Environment Council (Conama), which reduced civil society participation and increased the presence of members of government.

Other controversial measures began taking form, such as the discussion of Proposed Bill 191/2020, which seeks to regulate prospecting and mining on indigenous lands. Publicly defended by Bolsonaro, the bill is being processed in the Chamber of Deputies and will be voted on with urgency. In another extremely harmful action, on April 22, 2020, Funai published Normative Instruction (IN) No. 9—a type of regulatory act issued by an administrative authority—which releases all non-approved indigenous lands for purchase, sale, and occupation. This impacts areas that are still under study, territories delimited by the agency itself, lands ceded by the federal government to indigenous peoples, in addition to reference areas meant for isolated indigenous groups.

In April of this year, the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) published the Rural Conflicts in Brazil report, which covered 2021 data. The study reported over 1,760 conflicts in Brazil’s rural areas, with most of them resulting from land disputes. According to the report, the number of killings in the countryside in 2021 was 75% higher than in 2020 with a total of 34 people murdered last year. Another alarming fact is the 1,100% increase in the number of deaths resulting from conflict. These are deaths resulting indirectly from the violence perpetrated against rural and rainforest populations, rather than outright homicides.

The executions of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira express both the restriction of freedom of expression and the persecution of those who fight for the environment. Phillips participated in a meeting organized by RioOnWatch in 2019, which brought together community reporters and international correspondents. In the words of Theresa Williamson, Executive Director of Catalytic Communities (CatComm),* Phillips was one of the most conscientious and sensitive international journalists towards the city’s favelas. “If you look up the stories he wrote about favelas and associated issues, there were a lot of meaningful, emblematic, and well-written stories. His is a great loss to this world.”

Risks Imposed on Reporters in Favelas and Peripheral Rio

Much more than simply exemplifying what is happening across the country, the state of Rio de Janeiro can be viewed as a kind of microcosmic laboratory to understand the mechanisms at play across Brazil. The so-called “militia state” had its origins in the state of Guanabara (formerly Rio de Janeiro municipality). A recent landmark of this process was the assassination of City Councilor Marielle Franco and her driver, Anderson Gomes, in March 2018. The Lives in Struggle report also points out another significant 2018 event: the federal military’s intervention in the management of the Public Security Secretariat of the State Government of Rio de Janeiro.

According to the Intervention Observatory—which is an initiative to monitor and publish rights violations brought about by federal intervention in the state of Rio de Janeiro—there were at least 206 cases of abuse and violence, accounting for a total of 1,375 deaths resulting from police action during the study period in 2018.

Another important factor was Governor Wilson Witzel taking office in 2019. In his first year as governor, deaths reported by police as “self-defense” rose by 18%. The public security agenda is one that most galvanizes favela media activists. Relatedly, reporting abuses by the police and other authorities is not easy, especially for those who live in the areas where such violations are committed.

Thaís Cavalcante is a journalist with extensive grassroots journalism experience. Born and raised in the favelas of Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, she has worked with several community media outlets, including O Cidadão, Maré de Notícias, Favela em Pauta and Voz das Comunidades. To Cavalcante, those who try to offer another account of their daily lives are opposed by the police and political forces. “What you see are threats, a lack of response… we’re dealing with State neglect. I think that this is a very important point for us to evaluate—how we are made invisible, both in our grassroots news outlets and in our work itself,” said Cavalcante.

For Cavalcante, the difficulty of implementing the Freedom of Information Law (LAI) is another barrier that grassroots journalists encounter in performing their jobs. “We have the freedom to get information that is already made public. Grassroots journalists endure various such obstacles, whether directly or indirectly.”

Activists fighting against religious racism are also under threat. Heloisa Helena, known by her religious name of Luizinha de Nanã, is a Candomblé priestess. She lives in Guaratiba in the West Zone. Recently, she experienced a tragic situation: her garden of sacred herbs, which she grew at the edge of the Jardim Piaí Channel, was set on fire.

The herb garden was not used exclusively for religious purposes. It was meant to help rejuvenate and preserve the Jardim Piaí stream, as well as provide a tool for environmental education for surrounding residents. “I have been dealing with bigotry and religious racism for many years—since I was little. In the past, I didn’t recognize or know what racism was, and I thought that the whole world was beautiful and marvelous. When you start to get the idea that other people are doing things to offend you because they dislike the color of your skin, it’s a very sad reality,” said Luizinha.

Luizinha was impacted by the forced evictions in Vila Autódromo, which were promoted by the City of Rio de Janeiro in the pre-Olympic period. According to her, racism is the common denominator between these two experiences. Luizinha recalled that a “white Catholic church” was given the right to remain in Vila Autódromo—a right denied to the afro-Brazilian religious site that she maintained in the neighborhood. “According to real estate developers, poor and smelly people aren’t wanted in Barra da Tijuca. That’s what they consider us to be. The government thinks the same thing too. If the government thinks like this, what else would the citizens think?” said Luizinha.

The state government of Rio de Janeiro recently implemented its latest security initiative, the Integrated City program. The Jacarezinho favela, in the city’s North Zone, was chosen as the pilot community for the program. However, community activists and residents have—from the very beginning—denounced the program’s lack of transparency as well as the mass militarization of the community in lieu of any real social change.

Bruno Sousa is a communications coordinator at LabJaca, a Jacarezinho favela-based research and training laboratory dedicated to the production of data and narratives concerning favelas and peripheral areas. He said that the Integrated City program has transformed the dynamics of the group’s work and that its strategies of action needed to be revisited. “We have been avoiding making recordings inside Jacarezinho. Audiovisual work is one of our trademarks. The favela really was taken over, the exits to Jacaré have been occupied, and we have experienced looting, theft, and all kinds of human rights violations within the community. Considering we’re on the front line of all this, we’ve been very worried,” said Sousa.

On May 11, the Civil Police tore down a memorial built in honor of the victims of the May 2021 Jacarezinho Massacre. To Sousa, this was meant to send a message to favela activist groups. Police operations within the community have limited the activities of groups like LabJaca. Favela leaders have been forced to join protection programs after the complaints they issued, especially after the massacre. “The territory is unstable. We know that the drug sale issue has not ended here, not even with the arrival of the Integrated City program. This is in addition to the lack of dialogue with the police as an institution, which is not on us—in reality, it’s systemic and on the institutions,” said Sousa.

The Situation in the Baixada Fluminense Region

If the situation in the capital city seems bleak, it is even more complex in the cities of Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense. The Lives in Struggle report revealed that fatality rates are higher there than in Rio proper. The most common victim profile is a young man—under 24 years of age—black or brown, with a low level of formal education. Of the purported police self-defense cases in the state of Rio, 30% of them occur in Baixada Fluminense. The region also accounts for 60% of all registered disappearances in the state.

According to Fabio Leon, a journalist and organizer at Fórum Grita Baixada, the area has a history of violence, with a strong presence of death squads, which are given public legitimacy through the narrative of needing to “maintain law and order” against crime. The conservative logic follows that some human beings are “killable,” only encouraging the legitimacy of these groups. “This happens primarily in areas where black and brown people are concentrated, which is a large portion of the Baixada Fluminense,” said Leon.

The militarization process has also spread throughout the region, which has had consequences on the political actions of activists. Reporting police violence requires a careful strategy. “Unfortunately, for security reasons, we only use data which are available from the Public Security Institute. We produce our newsletters based on these statistics. So, this is how we found a way to, at the very least, question what these numbers mean,” said Leon.

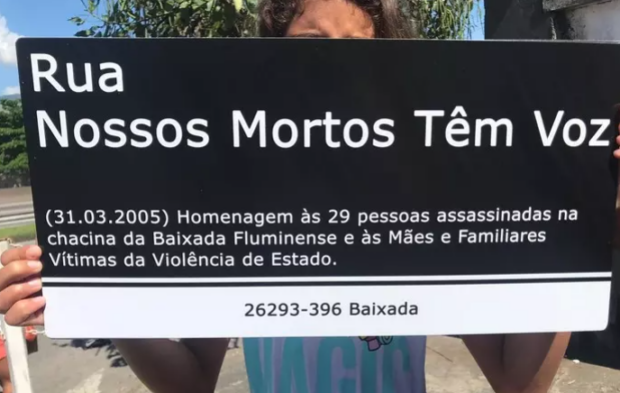

Another strategy adopted by Fórum Grita Baixada was the production of the documentary Our Dead Have a Voice, produced by Quiprocó Films and directed by Fernando Sousa and Gabriel Barbosa. The film features the testimony and leadership of the mothers and family members of victims of state violence in the Baixada Fluminense region.

During the last election cycle, many human rights advocates had difficulties with campaigning in person. “We’ve had some human rights advocates try to run in past elections. We received many reports from people who ran against seats occupied by Bolsonaro-supporting politicians and they ended up receiving threats,” said Leon.

During the last election cycle, many human rights advocates had difficulties with campaigning in person. “We’ve had some human rights advocates try to run in past elections. We received many reports from people who ran against seats occupied by Bolsonaro-supporting politicians and they ended up receiving threats,” said Leon.

The Brazilian Committee of Human Rights Defenders has put together a series of suggestions for improving national policies that are meant to protect activists. Among the suggestions, the following stand out: the establishment of technical cooperation agreements and protocols between the justice system and the state security apparatus; the creation of an assistance and health network; the completion of the land demarcation process for indigenous peoples and quilombolas; the identification of and accountability for those who make threats; an increase in the budget earmarked for protective equipment and to reduce bureaucracy; improvements in the methodology of government services, with special attention given to the specificities of each human rights defender served, as well as a review of the guidelines of the National Program for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders; and an update and approval of the legal framework for the program.

Cavalcante believes that supporting community leaders, non-governmental organizations, and civil society groups helps protect grassroots journalists. “If we were to be recognized by the official press as communications professionals, we wouldn’t be thought of as less than because of where we live or what news outlet we work for. Most importantly, politics directly influences this. I believe that if Bolsonaro leaves office, we will be able to find a way to fight for democracy and for the democratization of communication.”

Bruno Sousa met Dom Phillips when he worked for The Intercept Brasil. He recalls his generosity and politeness as Sousa was beginning his career there. He left us with a message of mourning and solidarity for the situation that activists and journalists are facing throughout the country. “It is very unfortunate that all of this has happened—not just to him, but to all journalists and human rights defenders in Brazil. Here, we are often afraid to say what we know, what we see, or what we think, precisely because there are opposing forces that are stronger than us. Brazil—not that it wasn’t already—has increasingly become a militia state, which leaves crimes like these unpunished. So, all my solidarity is with Dom, Bruno, and their families.”

Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a grassroots journalist, contributor to the Paratininga Communications Center, and the creator of the Antena Aberta podcast.