This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Center for Critical Studies in Language, Education, and Society (NECLES), at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), to produce articles to be used as teaching materials in Niterói public schools.

How does community-based journalism in the favelas work to cover one of the most important elections in the history of democracy in Brazil?

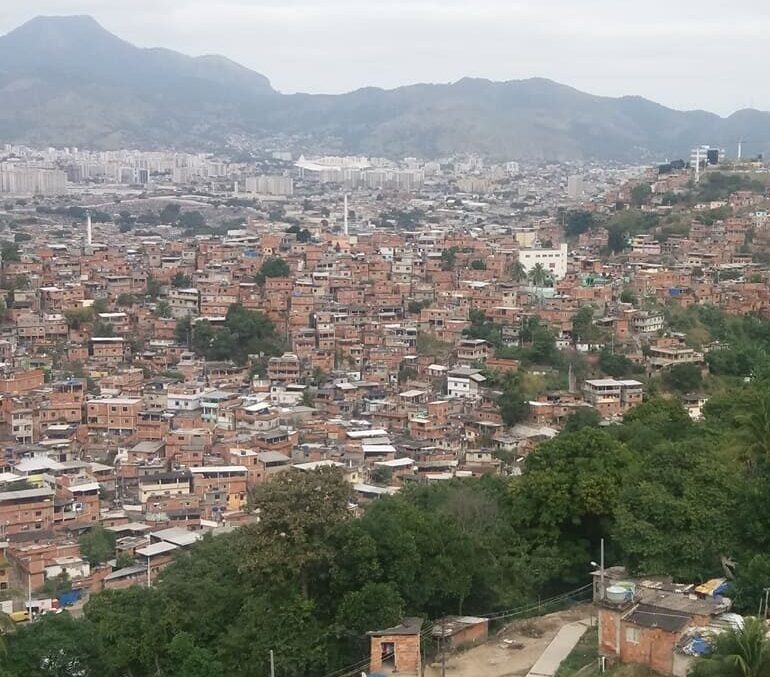

RioOnWatch has asked this question to grassroots journalists from many different Rio de Janeiro favelas in an unprecedented election year—one of the most important since the end of the dictatorship and political reopening of the country in 1985.

Progressive and far-right political forces are in opposition in the electoral contest. According to historian Heloisa Starling and political scientist Miguel Lago, in an interview for Folha de São Paulo, Brazil isn’t just dealing with a polarizing political dispute like those that have come before it: this is unprecedented, a struggle that will define the future of our democracy. What’s at stake are two different forms of government, two different political agendas, two different views of rights and of economic priorities.

Meanwhile, there are concrete and daily concerns over the return of hunger and rising prices for cooking gas and basic food staples. These are outlined in the accounts of the community journalists interviewed who are themselves residents of different favelas across Rio. Alongside this, there’s a strong fear of threats and reprisals—even the risk of death—which reveals how Brazilian democracy remains selective and does not guarantee freedom of expression.

To the community journalists interviewed, “there has never been full democracy” in Brazil. Pedro* reports:

“I don’t intend on covering the electoral dispute [here in the favela]. I intend to publish work that can be used for political education. This can be done. Questions like, ‘Are you registered to vote? What can you not forget on election day?’ There are many different challenges in covering elections in the favelas, from security to not showing favoritism toward specific candidates. You can’t mess with certain forces, with powers you don’t know, but that might be aligned with existing associations inside or outside of the territory with at least two parallel powers (militias and drug traffickers).”

The full exercise of citizenship rights by favela residents is a complex issue, both due to the absence of fundamental rights—like access to clean water, sanitation, public transportation, education, and housing—and because freedom of speech is intentionally curtailed. Whether or not they live in the favelas, grassroots journalists say they do not feel safe to freely report on elections. Maria* asks:

“If we’re talking about democracy, we shouldn’t have to refer to it as ‘full democracy.’ Just ‘democracy.’ In the absence of a true democracy—that is to say, a complete and full democracy—we add adjectives to democracy, defending what we have, because we understand that it’s still better than an openly authoritarian state, like what happened in the dictatorship. Still, the fact is that our democracy still has many flaws, especially within the favelas. So how am I supposed to feel safe to cover the elections?”

According to the journalists, even reporting on public policy during an election year “could be a risk.” Opening up debates on structural problems in the favelas or reporting on public works being done may seem like a writer is taking a position of opposition or favoritism for specific candidates. It could be seen as “an attempt to influence the vote in the favelas.”

Giving visibility to public works or specific problems may displease candidates that are supported by paramilitary forces, the State, and other political and institutional forces, both within and outside a specific territory. As José* explains:

Giving visibility to public works or specific problems may displease candidates that are supported by paramilitary forces, the State, and other political and institutional forces, both within and outside a specific territory. As José* explains:

“Not covering the elections in the favelas in community media also has to do with these media outlets being part of local organizations. So any stance that may seem to favor a specific politician, on the Right or on the Left, from any party, may seem like an official institutional stance. And this is very complicated and complex, considering it can put us at risk [of reprisal].”

Rosa* expands:

“This structure means that we [in community media] aren’t able to cover certain subjects in the same way commercial media can. In itself, living in the territory brings certain limitations—not just because you are a resident, but because you are considered a lesser journalist. Living in the favela can also mean you end up being labelled a ‘snitch’ within the territory. Outside the community, people might consider you to be a producer of content that is not considered reliable.”

This comes in spite of studies that show that grassroots journalists bring more nuance and a wider perspective to news coverage, in comparison to traditional media.

Without Freedom of Speech

In total, RioOnWatch contacted twelve grassroots journalists who were born and raised in favelas from the entire Metropolitan Region of Rio. Eight agreed to be a part of the article; five under the condition that their names and neighborhoods remained anonymous.

To preserve the security of these sources, while also making visible the self-censorship of voices from the favelas and the climate of insecurity in these territories, the identities of all anonymous interviewees have been concealed. These interviews have been separated from the others. José* says:

“It’s taboo to talk about this, but the truth is that we can’t exercise our rights. We cannot have complete access to the freedom of the press and our rights of expression in the favelas. There is no legal or institutional protection—there’s no protection available to a community communicator. Grassroots journalists have to be responsible for their own protection in an environment of social conflict and political debate. That means that election coverage, when it happens, is extremely self-censored. No one needs to make explicit threats: it’s something people from these territories just know and feel.”

According to community journalists, community media cannot have the same role for society in covering the elections as the coverage found in commercial media sources. They can’t, for example, produce reports that take a thorough look at candidates’ proposals, especially for more “local” positions such as state deputy or governor. Jurema* says:

“I think talking about democracy is an extremely complex issue here. The meaning of democracy involves access to rights that are either denied or limited in the favelas, directly or indirectly, as well as the issue of public security. Social spaces and freedom of expression are controlled in the favelas: local paramilitary forces, for example, are often evangelical, and that makes the evangelical culture so strong that it both oppresses other religions and promotes certain candidacies and policy proposals that are supported by the churches. This means these paramilitary forces can curtail political campaigns in the favelas.”

Focusing on Solutions Journalism and the Provision of Services

With all of this in mind, how can community media keep the favela informed during the electoral period? The question that kicked off our conversation remains unanswered.

Although there isn’t a single or fully correct answer, it’s possible to perceive from the journalists’ reports that community media outlets use a set of experiences and survival strategies that allow them to exercise freedom of speech even during electoral periods. These are articulated through solutions journalism and the educational power of community journalism.

Jefferson Barbosa, executive director of PerifaConnection, explains:

“When we think about elections, we, as communicators from the peripheries, always think about how we can explain what each political role actually does. Deep down, I believe that election coverage in the favelas has always been like this. We put forward the proposal of political education. The key turning point from the last few years is that we have also tried to direct people toward certain specific agendas, such as public transport, health, education and unemployment. This can help favela residents and people from the peripheries choose the candidate they want to vote for.”

Creating a platform to dispute common narratives about the peripheries—using a network of over 20 journalists from the favelas—PerifaConnection intends to strategically depolarize the narratives surrounding this year’s elections using “creativity in approaching these themes.” The proposal dubbed the “cabinet of love” is not a specific project but a practice.

Creating a platform to dispute common narratives about the peripheries—using a network of over 20 journalists from the favelas—PerifaConnection intends to strategically depolarize the narratives surrounding this year’s elections using “creativity in approaching these themes.” The proposal dubbed the “cabinet of love” is not a specific project but a practice.

Barbosa explains:

“It’s something to dispute these narratives… the objective is to clarify information and depolarize so that people can decide on the best candidates and choose their vote from the point of view of their own reality.”

To Barbosa, this is the turning point for producing communication and interacting with the public about elections within peripheral communities:

“We [reporters in the favelas] cannot occupy a political space because next to no journalist would actually be able to do that. That would make our position—being a journalist, providing information—infeasible. This is why we talk about rights and not about candidates.”

For Michel Silva, editor of Fala Roça, access to these rights is what’s important in the favelas. This means that electoral debates and coverage about the elections by community media are an altogether different story. The debate in the favelas, as Silva says, “isn’t about the Right or Left” but about more urgent issues in day-to-day life.

“Favela residents are not very connected to ideological issues of Left or Right. They’re more concerned with urgent matters of survival. For example, how much does cooking gas cost? They want to know whether there will be a spot for their child in the community day care or at school next year. They’re worried about whether or not the price of meat is going to go down.”

Silva also explains that during electoral periods, it’s possible to provide coverage for residents who stand for election but not to favor any specific candidate.

In Silva’s opinion, “the most important thing, as always, is to raise the political awareness of favela residents.” One way to work towards this goal is through solutions journalism, debating a topic in report format. “We shouldn’t just focus on informative journalism, but produce knowledge on a certain topic based on data and a specialized perspective.”

Working from this perspective and after careful financial analysis, Fala Roça opted to direct its efforts “toward covering the actions of community cultural groups, such as the launching of the Rocinha Cultural Map,” Silva says. For the elections, the paper proposes to quickly cover the results of the first and second rounds of voting, while also working on political education.

Jéssica Pries, journalism coordinator at Maré de Notícias, says that they are preparing to cover and report on this year’s elections giving “visibility to the historical processes of violence and the violations of rights committed by the State in the favela and peripheral communities, legitimized daily by a society that is structured by racism.”

According to Pires, the paper’s team organizes itself to report on “the real demands of the group of favelas that make up Maré, mapped and identified collectively, with the participation of the people that make up these spaces.”

Pires also highlights that: “we need to understand communication as a tool to strengthen democracy, which has become weaker over the past few years.” For her, community journalism is central to this process, because it is capable of amplifying local voices and giving visibility to the empowerment of the peripheral population, which is frequently marginalized.

A Different Logic of Communication

Born and raised in Maré, in Rio’s North Zone, Gizele Martins has been a grassroots journalist for 20 years. Today, Martins is a part of the Maré Mobilization Front, a collective of community journalists that organized in response to the impacts of coronavirus in the favela. The initiative became known as the Maré Front.

Martins highlights that community media is essential to the political debate, but not just in electoral periods. To Martins, “community media are able to influence the vote of people in peripheral communities and the favelas because they can take on an educating role, not simply report.”

Martins highlights that community media is essential to the political debate, but not just in electoral periods. To Martins, “community media are able to influence the vote of people in peripheral communities and the favelas because they can take on an educating role, not simply report.”

This occurs, above all, because community media works with a different logic in communicating with its own territory. In Martins’ view, the most important thing is to “open up a dialogue with people, not just discuss the vote in terms of choices like A, B, or C.” She describes a communication project carried out last May by youth from the Maré Front who spoke about electoral rights with vulnerable residents that had no access to other methods of communication:

“[In May], we in the Maré Front distributed 300 hot meals to the vulnerable, unemployed local population, who do not have homes, as we do every Saturday. During the distribution, young people from the Maré Front added a note that asked, ‘Have you registered to vote?’ and explained the importance of voting. At first, I saw this as something really odd because we’re talking about people who were completely vulnerable and dealing with hunger but later on I considered the intervention to be very important. This sort of community action creates new dialogues, speaking directly about rights with a population that cannot be reached by the Internet, television, or the candidates themselves. Democracy is not just about security, it’s also about education, sanitation and the right to eat. The Front has been organized and close to this population from the beginning of the pandemic. The young people [in the Front] live here, the journalists live here and… they know older people, like me, who work in community journalism. It’s not just a passing thing to talk about the election, but a constant dialogue. Residents feel comfortable talking to us, including about the elections. They know we are not using them to get a vote for someone.”

Martins is the author of Militarization and Censorship: The struggle for free expression in the Maré favela and is working on a PhD in Communication and Culture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). To her, censorship in the favela is a reality, but community journalism may be a tool to resist and fight for real democracy in these territories.

In the book, Martins analyzes and reports on the military occupation of Maré between 2014 and 2015. This occupation, during a democratic government from the Left, was responsible for silencing community media in the favelas by using the Guarantee of Law and Order (GLO):

“It’s important to talk about and emphasize this. It didn’t happen in the whole city. It was only in a few territories, exactly where the poor and black populations live. It wasn’t across Brazil or even the whole city, thankfully! But I lived it, unfortunately, in Maré for two years. I had my right to free speech violated: I was censored, and so were other journalists, even festivities were censored. It was the worst moment I’ve lived through as a community journalist, in twenty years of journalism, and this period needs to be remembered. We lived through the sad years of what was essentially a military dictatorship in Maré, during a period of democracy. This can’t be forgotten: we need to bring this debate to the candidates. We can’t pretend that nothing happened, even though we know that we don’t want the extreme right to be in power.”

The Guarantee of Law and Order is a provisional measure that grants police powers to the Armed Forces, especially when “there has been a depletion of the traditional forces of public security, in extreme situations of disturbance of the civil order,” as defined by the Ministry of Defense. It is a special public security provision that was used throughout the military dictatorship and remains in force as part of Article 142 of the federal constitution, which originates from Complementary Law 97/1999 and Decree 3,897/2001.

Martins asks:

“We don’t have full democracy at all. I’m talking about the equal distribution of the right to live that we shout about every day. The favela and the periphery live with State actions left over from the military dictatorship. Even today there are forced disappearances, mainly in peripheral areas in the Baixada Fluminense. Even today the favelas suffer with massacres, military operations resulting from the military dictatorship—much like the forced evictions were. How can we say that we have democracy?”

In 2018, using the GLO, the Michel Temer administration promoted a new military intervention—although this time throughout the entire state of Rio de Janeiro. This had many consequences for the favelas. Martins points out:

“In 2018, the formal city of Rio itself had to deal with a military intervention. And when the formal city suffers, that’s a sign that things in the favelas are much worse. The formal city started suffering in 2018, so just think of when the suffering began in the favelas… I talk a lot about the formal city to make a comparison, as a measure for this situation. I think this is an argument that can be made: when the right to the city is taken away from the places that are considered an integral part of the city, imagine how it is in the favela.”

She concludes:

“The formal city needs to understand that the favela exists and not just deny our existence by traveling down Avenida Brasil with their eyes closed. If the formal city today is experiencing abandonment, rising prices and whatever else, it needs to understand that the favela has been suffering from these very same things for much longer and that things are much worse there. I say the same thing about censorship and the lack of freedom of expression in the favelas: if, with the current government, there are journalists who work for commercial media being attacked and threatened, just imagine how it is for us, community journalists. So we need to understand the favela as part of the city.”

Brazil Drops in Freedom of Expression Ranking

According to a survey from Article 19, Brazil has had a “shocking decline in both real and relative terms” in its ranking on The Global Expression Report in 2021-2022. In 2021, the number of attacks on journalists and media sources was the highest since the 1990s, at 430 attacks. Since Bolsonaro became president in 2019, the number of attacks against journalists has risen every year.

This document shows that between 2015 and 2021 the country fell 58 positions on the global ranking of freedom of expression reaching 50 points and the 89th position, its worst ranking since the survey was first launched in 2010. The report has a scale of freedom of expression that ranks countries on a 0-to-100 scale, with zero being a country in crisis and 100 being one that has complete freedom of expression.

The organization compiles these numbers by analyzing and providing metrics on freedom of expression around the world. This reflects on the guarantees of the rights of journalists, civil society, and each individual to express themselves and communicate, without fear of harassment, legal repercussions, or reprisals.

*Some interviewees have been given pseudonyms for their protection.