Since July 7, 2022, the Banhado favela in São José dos Campos, São Paulo, has been under siege by the Military Police and the Municipal Civil Guard. Truculent searches, cars fined, home invasions, the closing of businesses and the arbitrary sign-up of residents for social rent are some of the violations reported by residents.

“We have been residents of Banhado for a hundred years. We are descendants of indigenous people and quilombolas and lately we have been suffering attacks from the municipality, more specifically from the city government. They’ve been violating various rights, breaking the law, because the issue is a legal one and we are winning in court. Caught in a deadlock, the municipality is attacking the law to reach its objective.” — José Donizetti de Paula, Banhado resident

In November 2021, the Banhado community, located in the city of São José dos Campos in the inland region of São Paulo state, was the subject of a forced eviction order filed by City Hall. The request is the result of an ongoing legal battle between the community and the municipality that began in 2018.

The conflict between City Hall and the favela worsened after July 7, 2022 when a large number of heavily armed police officers, accompanied by the municipal Civil Guard, invaded the favela with vehicles, motorcycles, and helicopters, in a demonstration of military force. Police bases were installed and have remained in the favela on a permanent basis. Residents have reported cases of intimidation and abuse of authority.

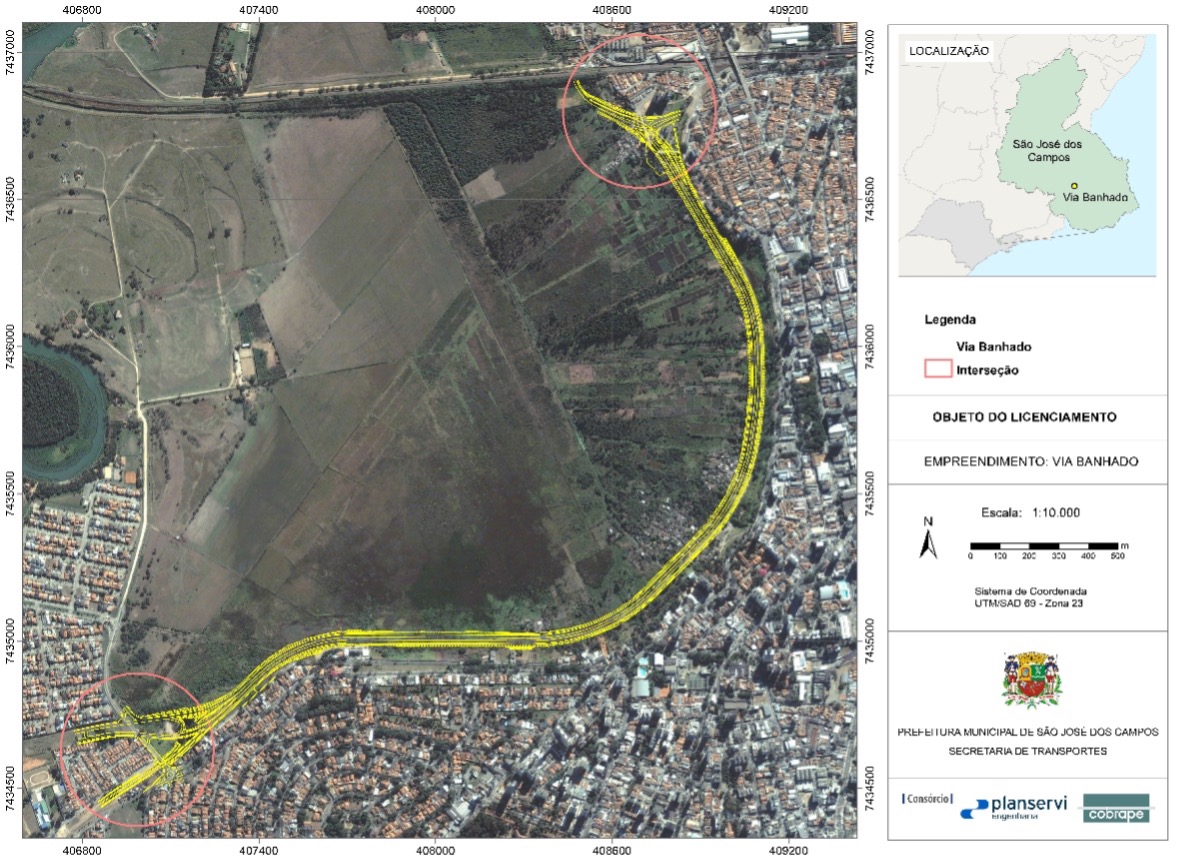

The Banhado favela, also known as Jardim Nova Esperança, is a century-old community with land conflicts dating back to at least the 1930s. The community now fights for the right to remain in the face of two major projects initiated by the City: the construction of an expressway and the transformation of the area into a nature park.

In short, the physical interventions in the Banhado area are part of a goal that is independent of an individual administration. The municipality wants to transform the landscape, while the community is the rightful keeper of the area it calls home.

The Landscape Reveals Itself: The Territory of Life

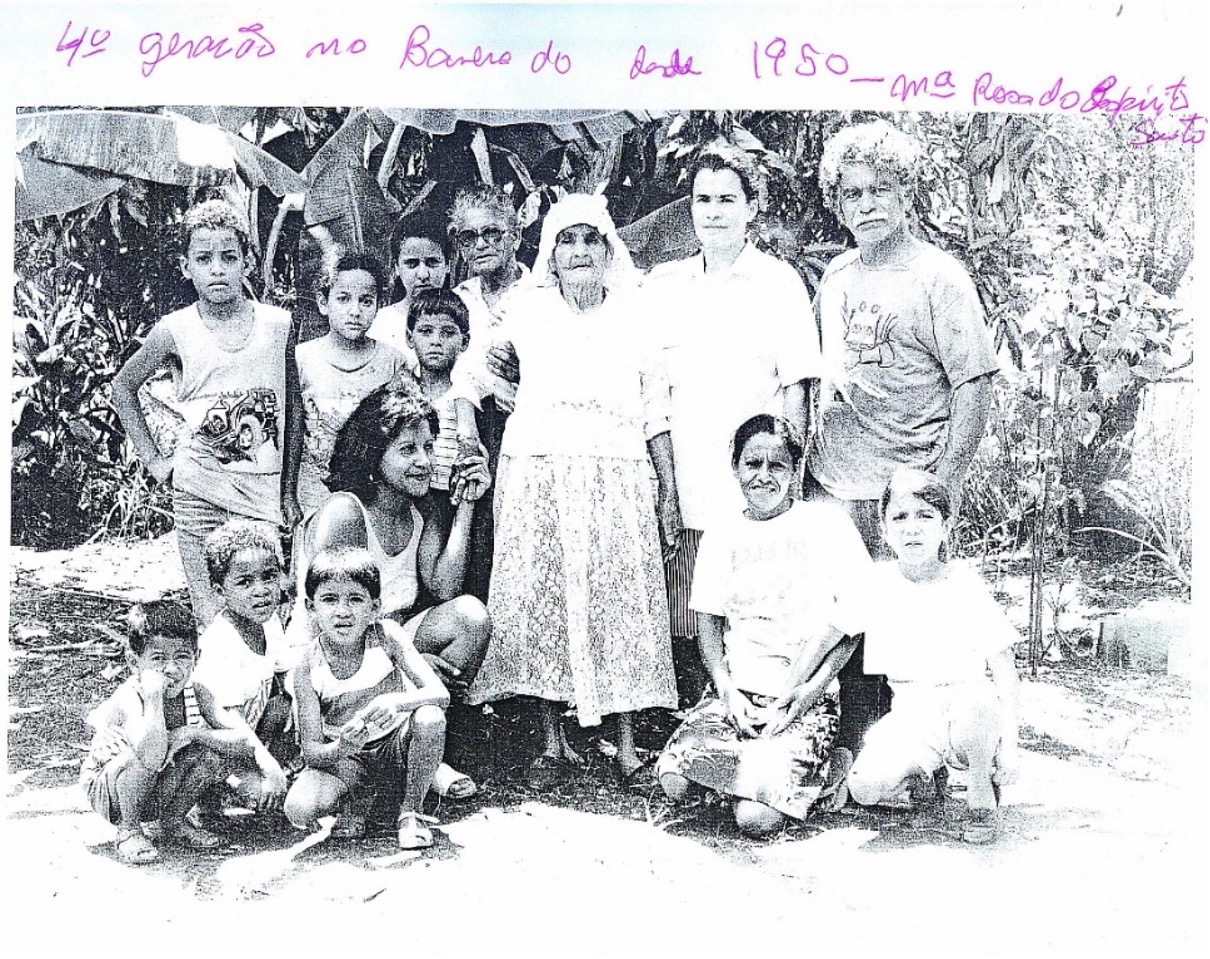

The Banhado community was the first favela in São José dos Campos. Currently, it is officially registered as Jardim Nova Esperança, but it has been referred to by many names throughout its history. Records suggest that it was founded in 1931, followed by Favela Linha Velha in 1932.

However, interviews with the community reveal an alternative view of the ancestral origins of the occupation. According to its oldest residents, Banhado was likely established before the period commonly accepted by historians, made up of the surviving families of quilombos and indigenous villages. In the 1930s, many families of Japanese, Spanish, and Portuguese origin emigrated to the region.

“We’re inside a city, right?… [But here in] Banhado you can find vegetables, fish farmers,… cattle farmers, pig farmers… And this forest of ours… these slopes of ours… if I want to eat pumpkin now, I just go to my backyard and get it… If someone wants a banana? They just go to the backyard and then there’s a whole bunch of bananas inside the house. You want to eat, you want to drink fresh milk? Go to Alemão, they milk their cows right there and then, at Renato’s father’s house. So, really, it’s a farm in the city!” — David Morais, resident of Banhado

According to the oldest residents, Banhado was known as Chapéu Velho (Old Hat), a name given by the people, which described the physical characteristics of the territory. The favela is at the bottom of a valley, sharing a border with, but at the same time separate from, the urban center of São José dos Campos. It is located on a stretch of floodplain of São José dos Campos’ Paraíba do Sul River; an area with a unique landscape and semicircular shape giving it similar characteristics to a shallow bay. Regional researchers Ademir Morelli and Ademir Pereira dos Santos characterize it in accordance with its three notable dimensions: the floodplain, the river and the semicircular slope.

“It is a land blessed by God. You see? That’s why we like it. I love Banhado. I love Banhado. It’s not that I like it, I love Banhado.” — Kardec Gonzaga, resident of Banhado

São José dos Campos emerged as a village in 1680 on the plateau that borders Banhado and remained small and humble until it was elevated to the status of town in 1767, and then city in 1864. Banhado, on the other hand, remained unconnected to urban life, almost always characterized as an urban void. Until the second half of the 20th century, Banhado was a floodplain, but from 1912 onwards, with the construction of the railway branch, the plain was gradually occupied with rice plantations. With the creation of drainage canals for rice cultivation, the landscape of Banhado followed the seasonal flooding patterns of the Paraíba do Sul River.

Residents’ accounts reveal the “Banhado of the past,” in which time and space was marked by the seasonal flood cycle of the Paraíba do Sul River. Residents reveal a space steeped in rich life experiences, permeated by the presence of the supernatural, of legends and storytelling. This lived experience of Banhado is represented as “a farm in the city,” a mix of rural and urban.

“These trees, they were all planted by our grandparents, by our parents.” — José Donizetti de Paula, resident of Banhado

Past Projects that Transformed the Banhado Landscape

From the 1935 decree that established the city as a Climactic and Hydro-mineral Resort—a health destination for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis—the city would eventually become a national security area. Due to its strategic position, the Aerospace Technical Center (CTA) was opened there in 1950. In addition, the newly opened Presidente Dutra Highway would become a catalyst for businesses opening along the new road.

In this context, Banhado started to be viewed in a different light by the city—no longer dismissed as an urban void. The first public intervention took place under President Getúlio Vargas’ Estado Novo, with the opening of the avenue that borders Banhado in 1939. The project was carried out under an Administrative Act issued by the State Intervenor (the São Paulo governor appointed by Getúlio Vargas), engineer Francisco José Longo.

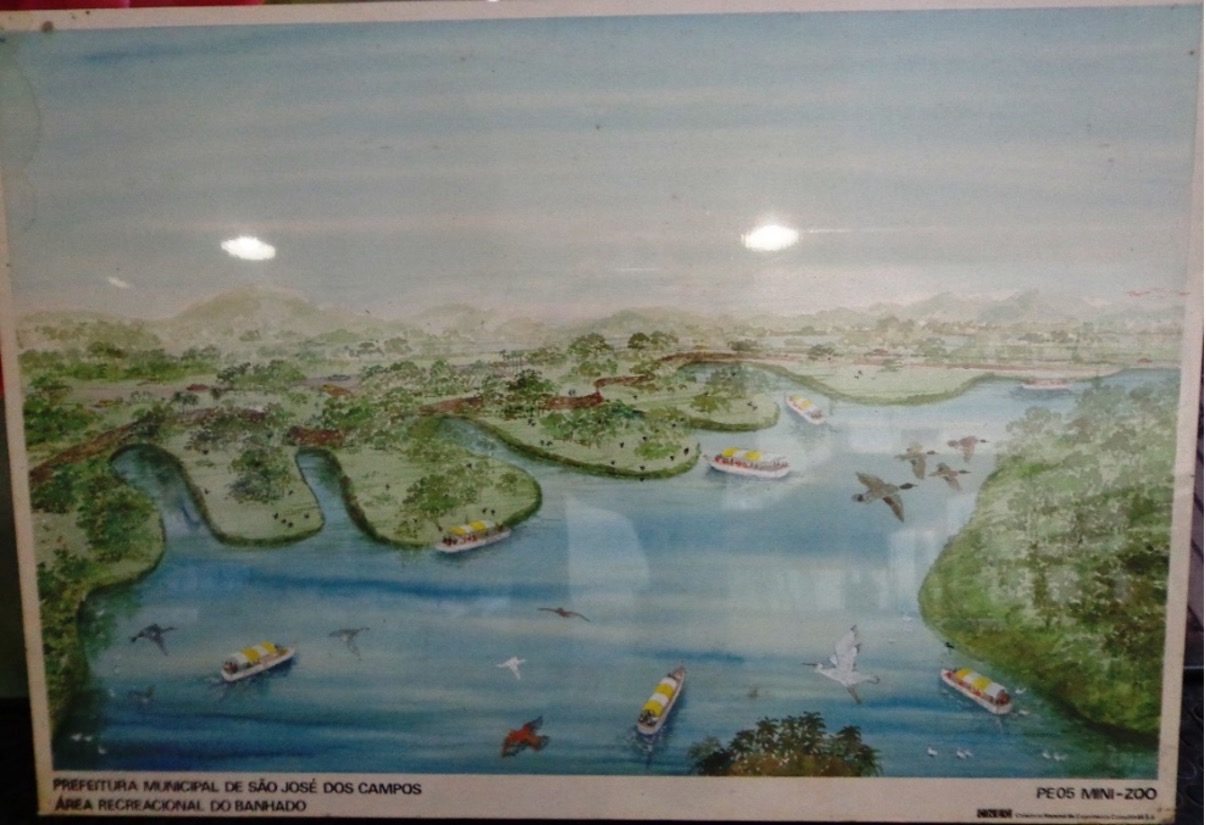

During the military dictatorship’s “economic miracle”, negotiations with the North American group Disney World were carried out to prepare a proposal for the Banhado Regional Park. The proposal would bring together Banhado’s bucolic elements—the water, beach, sunset—and the Mantiqueira Mountain range would become a theme park composed of lakes, green areas and gated communities. An elevated monorail station would also be built, traveling all the way to Greater São Paulo.

While these were ultimately economically unfeasible projects, they inspired future development initiatives. In 1981, the National Consortium of Consulting Engineers S.A. (CNEC) was hired to develop a new proposal. Titled the Banhado Recreational Area, the project was a downscaled version of the theme park project. This time, a surface subway was proposed, but this also never materialized.

Between 1991 and 1992, in a democratic period and with the environmental debates of Eco 92, a new proposal was developed by several segments of society. This proposal aimed to differentiate itself from the previous proposals which had focused on the notion of theme parks. Despite being innovative, the proposal prepared by the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB) shared several commonalities with previous proposals: notably the failure to acknowledge Banhado residents in park projects. All proposals required the complete removal of Banhado’s population as a condition for the creation of the park.

Banhado in the 21st Century: Building a Neoliberal City Model

In the early 2000s, the city government implemented Favela Eradication Plans, with the aim of removing the city’s favelas in a short period of time. Using the 1995 Master Plan to establish a public-private partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the goal was to raise funds for the Casa da Gente Project, linked to the Habitar Brasil-IDB Program run by the federal government. Although this was essentially a favela upgrading program, in São José dos Campos the project was set up to remove favelas completely.

Between 1996 and 2004, 24 favelas were removed. This favela eradication policy helped solidify the image of São José dos Campos as a “City without Favelas.” Favelas that resisted the removal policy are judged as an anomaly in the development process.

In 2002, Banhado became an environmental protection area in the State of São Paulo, under Law No. 11,262/2002. Interviewees talked about the stripping away of social policies that occurred in the neighborhood during this period. They emphasized the ostentatious presence of the police and harassment by municipal employees.

A few years later, the 2006 Master Plan established several guidelines to be implemented under a strategic plan—the Urban Structuring Program (PEU). Although initially planned as a road project, the IDB also established environmental improvement and administrative modernization conditions that the municipality was required to meet.

The introduction of Law No. 8756/2012 further encouraged the restriction of human occupation in Banhado, and led to the creation of the Banhado Municipal Nature Park. The most crucial issue arising from this law was how it changed the way that property is viewed. This change would determine the fate of local families. Within an environmental protection area, properties are allowed to remain, but only if they are compatible with the environmental functions of the area. In nature parks, the land is perceived as being publicly owned, therefore privately owned property is not allowed. This change in the law consequently delegitimizes the rights of the community to remain living in Banhado.

In 2013, during the municipal elections, the elected candidate maintained the same position with regard to Banhado as his predecessors, despite making commitments to the community. The political disillusionment of Banhado residents intensified.

A study commissioned by the elected mayor advocated the building of an expressway and the removal of Banhado residents. The area of Jardim Nova Esperança was classified as being at risk due to the potential of a mass movement of the slope. Additionally the disposal of untreated sewage was pointed out as a polluting element in the area.

Residents of the neighborhood report that, over the years, several registration surveys were carried out in the community, but the objectives of these surveys were never fully disclosed. However, it is commonly accepted that these surveys have been utilized as a way of convincing families to leave Banhado.

One of the techniques used by the city government is the practice of demolishing the houses of residents who had agreed to leave the favela, and leaving debris in place where the house once stood. This is a technique which leads to a growth in disease-spreading insects and animals and makes worse the already difficult life of residents.

“The Banhado community is an emblematic community… It’s very old. Located practically in the center of the city. And it is a community that the government abandoned for many years… It is a community criminalized by the public, with constant threats of removal of this nucleus, of the extinction of this urban nucleus. From the point of view of the authorities, ending the precarious conditions some families lived under, and still live under, would happen via the physical elimination of the community, and not by the elimination of the conditions… Normally it is social work professionals who seek out families, saying they’ll have to leave, and if they don’t leave they will have to leave by force. Specifically here in Banhado, we had a series of problems, because there were misleading questions in the presentation of the de-favelization project, in which the community was asked where they wanted to go. They weren’t asked if they wanted to leave or stay, if they wanted to regularize the neighborhood, but where they wanted to go. And then, based on these records, the conclusion was reached that more than 90% of the community wanted to leave here.” — Jairo Salvador de Souza, Public Defender of the State of São Paulo

Another practice observed is the process of freezing neighborhood projects for an indefinite period of time by prohibiting any new construction, expansion, or renovation of existing properties in the area. Jardim Nova Esperança has been “frozen” for over 16 years, with residents unable to renovate their properties, causing further deterioration to the houses there.

“If the quality of life here today has worsened, it is thanks to the local government. Whether it’s the old administration, the last one, or the current one, [the way we are treated] doesn’t differ at all.” — Renato Leandro, resident of Banhado

From the 2000s onwards, residents who accepted the proposal for housing assistance began to be transferred to housing developments on the outskirts of the city. The initial dream of attaining decent living standards quickly turned into a nightmare for the majority of residents transferred to the new developments: all the complexes were built without proper land titling, with various structural problems, and without individual water meters.

In 2017, Banhado residents filed a formal request for land titling under the category of Social Interest (REURB-S). The request for titling was based on Provisional Measure No. 759/2016, which would later be converted into Law No. 13,465/2017.

On May 18, 2018, the Public Defender’s Office was invited by the City to a meeting where the Casa Joseense Program was presented. The Public Defender’s Office committed to submitting a housing regularization proposal. On June 18, 2018, the Banhado Land Titling and Upgrading Plan was sent.

However, City Hall simply ended discussions and resumed harassment of the community, installing a control point for those entering and leaving the community and putting roadblocks on the main road to the favela.

Currently, the situation involving the Banhado favela lies in the courts, with both sides hoping for drastically different outcomes. The case filed by the Public Defender’s Office and the Society of Friends of Jardim Nova Esperança calls for the city to be ordered to produce an urban titling project in partnership with the Banhado population. The municipality, on the other hand, calls for public civil action against the residents, seeking a provisional emergency injunction to forcibly evict the residents of Jardim Nova Esperança.

An Imminent Massacre: São José dos Campos Is Producing a New Pinheirinho

On the eve of the presidential elections, the Banhado favela is facing strict surveillance, with police patrolling the main road to keep watch on the community 24 hours a day.

“The city government has intensified the attacks in several ways, and lately it has now decided to come in the early morning, and it attacked us on August 23, knocking down several houses, houses inhabited by people who live here in Banhado and who work here in the city… Four to seven families were affected by these actions. So now the court has taken action and given five days, starting on August 24, for the municipality to justify itself, for the city government to show up to report why they did this, given that it is already subject to a judicial process and prohibited from carrying out any action within the favela.” — José Donizetti de Paula, resident of Banhado

The justification of the Military Police is that the operation seeks to bring security to residents by confronting drug trafficking. On a Thursday afternoon, police forces conducted simultaneous land and air attacks, occupying the favela within minutes. Through the main entrance, heavily armed men with machine guns entered the favela in cars and on motorcycles.

After the violent occupation, there were home invasions and closing of commercial establishments. Cars were fined and the activities of waste pickers were halted, and a constant surveillance of the favela began. It is not uncommon for residents to be approached at the entrances and exits of the neighborhood and asked intimidating questions by the police: “where are you going?” or “do you use drugs?”

As usual, the city government’s tactic for demobilizing the community is to contact residents individually to get them to sign up for social rent. This strategy has not been able to guarantee the total removal of residents, but it creates tension between those who sign up to the proposal and those who stay.

“We here at the Evictions Museum in Rio de Janeiro watch with great concern all the cowardice and brutality that the century-old community of Banhado in São José dos Campos is facing. Enough of this eviction process. A favela that already has its [own] community plan ready and waiting for the governments to do their job: to upgrade the Banhado community.” — Luiz Claudio, Vila Autódromo

The city’s tactic of using terror to break the community’s resistance warns us that a new “Pinheirinho massacre” could occur in Banhado, recalling the violent eviction of the Pinheirinho favela in São Paulo in 2012.

“Everything that has happened here, [perpetrated] by the city government—all its actions—is the use of security forces against the poor… They don’t have the backing of the courts. So [the city government] is doing everything in a sneaky way, it comes with the security forces, it besieges the place, isolates, attacks and destroys houses. It’s cowardice, it’s a counterweight, it’s a really desperate situation that is happening here. Because they come with a huge apparatus of police and municipal civil guards and isolate the area. They don’t let anyone through. All armed with high-caliber weapons, and then they attack and tear down the houses. And they attack people. Recently there was an attack, fighting started between the police and residents because residents want to defend their homes, then the police go up, and attack and beat them. So we here, the population of Banhado, we have been suffering these last few days, and especially after this last incident that took place on August 23, suffering a lot from the attack by the municipality, from the attack by the city government of São José dos Campos.” — José Donizetti de Paula, resident of Banhado

In essence, the idea of transforming Banhado into a park, both under the theme park model and the ecological model, is based on the assumption that technical intervention, and technical intervention alone, could lead to a return of Banhado’s natural environment.

In the silent war against Banhado residents, the proposed urban planning has its roots in cleansing models. Consequently, Banhado residents are framed as obstacles to urban planning proposals within the institutional discourse. The theme park and expressway projects would be responsible for carrying out the “dirty work,” or for the “cleansing” of what it sees as tarnishing the landscape.

In fact, the political groups that control the municipality have never understood what Banhado actually is. The city has never been open to understanding Banhado, its culture, and its values.