This is the latest in a series of articles about Community Land Trust (CLT) experiences around the world. We selected a few cases based on their potential to inspire others. These examples show how varied CLTs are despite always having the same basic structure: a nonprofit organization made up of residents owns the land in an area, while residents own or rent the homes themselves. Our objective is to present lessons learned from international experiences with CLTs, so we can reflect on how to reach the model’s greatest potential in Brazil and overcome the challenges faced in other contexts. Here we explore the Tanzania-Bondeni Community Land Trust, a CLT located in Voi, Kenya.

The question of land ownership is a historic issue in Kenya. Over the past 30 years, many have fought for proper housing and addressing the nation’s informal settlements, resulting in a series of policies directed at the country’s low-income population, including the mass production of affordable housing. However, after these improvements are made, residents often sell their properties to higher-income individuals, continuing the cycle of land concentration and misaligning the objectives of public investment.

To overcome this vicious cycle, a group organized in the city of Voi to study the viability of a Community Land Trust as an alternative form of land ownership for informal settlements in the region. The Tanzania-Bondeni Community Land Trust was created in the early 1990s: it was the first CLT established on the African continent, composed of 530 houses. This CLT is in a valuable location in Kenya, close to the main highway between the port of Mombasa and Nairobi, the capital. As a result, there is extensive interest in the surrounding land, which makes it highly valuable.

The founders of the project adopted five central principles to guide the CLT’s operations:

- Participation of residents in land management,

- Banning absentee landowners,

- Prohibiting the sale of land,

- Maintaining community control of the territory, and

- Establishing individual rights over homes and other buildings.

Residents’ participation was one of the fundamental concerns in the Kenyan CLT, stemming from a shared understanding that only through constant community mobilization would it be possible to create a lasting solution.

Charging excessive rent in informal settlements is a common practice throughout the country. This led to the project’s concern with ensuring that all landowners be residents of the community, and thus resulting in a ban on absentee owners. The prohibition of the sale of land is a basic characteristic of CLTs and was one of the main reasons for choosing the CLT model, considering the risks of the concentration of land ownership and gentrification.

The next central principle—community control of the land—guarantees residents’ autonomy in formulating the CLT’s operating rules and that the community’s interests are being met. Finally, individual rights over the home were one of the main attractions of the CLT model that led to its adoption in Voi. Residents joined the CLT because the model allowed a degree of autonomy over the management of their own housing, with a guaranteed right to sell, make improvements, and leave homes to their children, among other uses.

One distinguishing characteristic of this CLT was its being developed and implemented by a diverse group of stakeholders, including the Voi Municipal Council in partnership with the Ministry of Local Government (MLG), responsible for providing political guidance and carrying out negotiations with other agencies, as well as the Small Town Development Project (STDP) of the German NGO GIZ (Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit). GIZ, a technical assistance agency for local development programs, was responsible for providing direct investment and technical support.

To access initial funding, residents formed housing cooperatives under the direction of the National Union for Housing Cooperatives in Kenya (NACHU). Subsequently, the project followed the same basic strategy as other CLTs: fighting for the acquisition of land through a non-profit organization, and then separate ownership of the land and the buildings on it. In the case of public lands, extensive negotiations with the Kenyan government were necessary, which prolonged the process.

One of the biggest practical difficulties was in the technicalities of Kenyan law, which prevented several land arrangements integral to the CLT structure concerning the separation of ownership over land and buildings, as well as the prohibition of the sale of land. The bureaucracy involved in changing this legislative framework led residents to organize and register as a private organization, entering into trust deeds that used the CLT’s management and maintenance guidelines. Afterward, the community, which was already organized, managed to transfer ownership of an area of public land to the CLT. The CLT, in turn, began to issue individual titles to the families that were part of the organization. This legal arrangement probably makes the Tanzania-Bondeni CLT the world’s first Community Land Trust established on public land, without formalized ownership under a non-profit organization.

Transaction costs involved in the formation of the CLT were significantly reduced by a series of different measures, including land donations, leased parcels, resources from city residents, and the support of GIZ. As a result, residual costs could be paid by residents within two years. While residents had initial costs, these were lower than the expenses of older government housing projects, and even lower when compared to rental prices in the area within the traditional housing market.

“If we decide to opt for individual deeds, some people will start to sell. What will happen to the children? Where will they live?” — Mama Fatuma, Tanzania-Bondeni resident

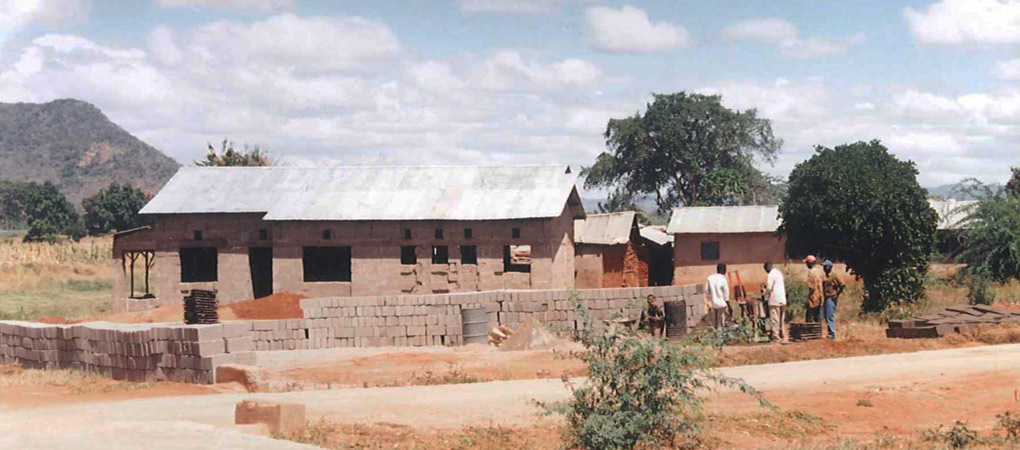

The Tanzania-Bondeni CLT was structured to promote the recognition of land ownership and affordable housing, but it also encouraged the implementation of adequate housing. Investments were made in infrastructure, such as the creation of municipal water pipelines, roads, rainwater drainage, and canals. Investments have also been made in the development of low-cost housing, based on basic housing plans and appropriate technology, with the help of the Housing and Building Research Institute at the University of Nairobi (or HABRI).

The Kenyan CLT model was of paramount importance to the local context, as it was able to help hundreds of low-income people gain legal access to urban land—a historic struggle in the region. The establishment of the CLT also helped provide essential services to the area, such as water access, electricity, and sanitation, as well as a sense of empowerment for the families who lived there, encouraging their participation throughout the process. In addition, the CLT prevented the expulsion of the area’s original residents following real estate speculation, which is a common phenomenon in newly regulated informal settlements in the country, caused by the increase in land value and pressure to sell properties.

“I am convinced… that this can be replicated anywhere.” — Gideon Muindi, former town clerk, Voi Municipal Council

In turn, the CLT also faced challenges, especially related to maintaining community mobilization efforts. Over the years, the mobilization process weakened; at the same time, conflicts grew over the management of the CLT, many of which were related to low rates of payment of administrative fees. Despite this weakened mobilization and distrust on the part of residents towards the CLT’s managers, the arrangement remains in force in Tanzania-Bondeni.

Kenya’s experience with the Community Land Trust model is symbolic and brings forth important lessons for CLT advocates. It was the first example of a CLT in both the Global South and informal settlement contexts. It marks a significant change in the implementation of the model, as it is now being adopted alongside land ownership measures. The experience demonstrates the CLT’s potential in guaranteeing the permanence of communities on their land and strengthening security of tenure in a post-regularization scenario. Above all, it teaches us the importance of community mobilization: without strong and continuous mobilization, the CLT model will not reach its full potential and will face serious issues in attempting to manage land and meet collective interests.