Clique aqui para Portug uês

uês

The “blackiteracy” project Rê Tinta was created to promote literacy among black children in Rio de Janeiro and help teach their classmates to be anti-racist. It all started through a comic strip, but is growing into a social policy that offers books by black authors and reading circles to the little ones.

“Blackiteracy”, or afrobetização in Portuguese, involves pairing literacy and anti-racist education in early childhood. The term, which has been gaining ground in the last decade, is based on the principle that no one is born racist. For this reason, it understands the importance of empowering children to reduce the harms caused by structural racism.

Representation

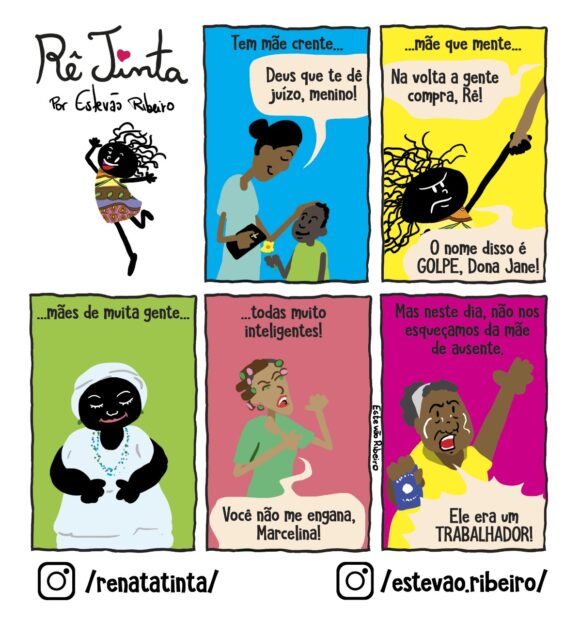

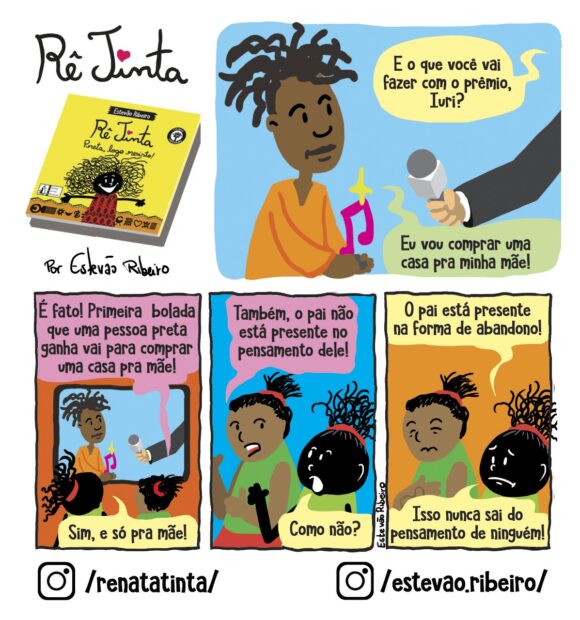

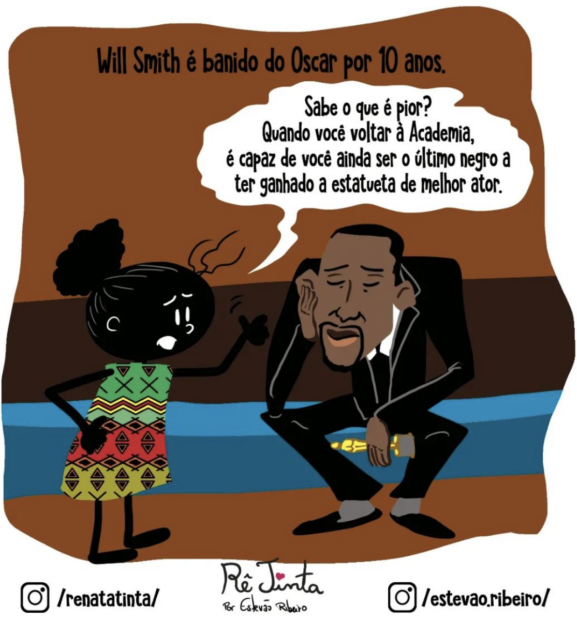

Father of six-year-old twins, both black with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Estevão Ribeiro decided to act against the lack of representation of black children in children’s books and comics. Fatherhood led Ribeiro, 43, to create Renata Tinta—Rê Tinta to fans, and also a play on words in Portuguese denoting dark skin and black pride—in 2018. The anti-racist comics empower children and adults and teach blackiteracy through social critiques that reflect on structural racism. And they’ve even become published books: Rê Tinta: I’m Black, Therefore I Resist and Rê Tinta and the Jamun Tree.

Born and raised in peripheral neighborhoods in the state of Espírito Santo’s capital, Vitória, Ribeiro moved to other vulnerable areas when he moved to Rio de Janeiro. Currently a resident of the outskirts of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro’s sister city across Guanabara Bay, he’s lived in the neighborhoods of Beltrão, in Fonseca, and currently lives in Santa Rosa. Aside from race-related themes, Ribeiro weaves in others such as religion, fatherhood and motherhood, politics, and ancestry into his work, from a black perspective. Rê Tinta has already reached nearly 15,000 followers on Instagram.

“Education is also part of our job. We have to share our knowledge, as many of our elders did with us. We can learn so much through stories. And so, just like someone in the community tells their stories, the griots share their stories from the past. We’re storytelling for our village too, a village that spreads out very far.” — Estevão Ribeiro

Trajectory, Obstacles, and Inspiration

Estevão Ribeiro always loved drawing, having begun at age 14. By age 21, he published his first comic strip in Espírito Santo’s Jornal Notícia Agora. After moving to Rio de Janeiro almost 15 years ago, his comic strips were published in the newspapers O Dia, Meia Hora, and Extra. In 2008 he created the comic strip Little Birds, published in Brazil, Nicaragua, Portugal, Panama, and Ecuador.

Being a black man and father of two black autistic girls led Ribeiro to create an empowered character, who’s educating other children like his own daughters.

“I’m a father of twin girls and they’re on the autism spectrum. One of them has slightly more trouble with speaking, so it’s yet another challenge. My biggest challenge at the moment is their independence. It’s like I’m working so that they can enjoy better conditions to increasingly develop and become independent adults. This is what I’m fighting for now. I obviously hope to be raising empowered, anti-racist girls, who are aware of their privileges.” — Estevão Ribeiro

The books telling the adventures of Rê Tinta are already in the hands of over 20,000 children from the Rio de Janeiro state public school network, teaching blackiteracy to kids of all backgrounds. And the story that empowers so many children almost never came to be, said Ribeiro. Because he almost gave up on drawing.

“I started drawing early on, but stopped because I kept running into people with much more talent than me, and I thought my talent was limited to writing. So I dedicated myself to writing until I was 20 years old. When I had to write my bio, I realized I had no biographic entries. So then I started drawing myself… I started working, but independently, because when you write comics, you always depend on a cartoonist. And not everyone is up for investing in stories as much as you, their creator, isn’t that right? From then on, this type of need ended up instilling a desire to draw, and I thought: I’m going to go back to drawing.” — Estevão Ribeiro

These days, Ribeiro feels that believing in his gift was the right response for his journey and for the journeys of thousands of other children and adults, black and white, around the world. “The Rê Tinta comic strips are featured in school tests. Some made it to university exams and others to educational textbooks. So I believe my material has contributed a little to education in this country.”