On the centenary of the demolition of Morro do Castelo, we recover the memory of this extraordinary and often forgotten geography essential to the history of Rio de Janeiro. Equipped with its own historiography, the hill’s slopes witnessed over centuries the pain of attempts to tame the misery, enslavement, unequal economic development, and rapid urbanization of the city. In 1922, the centenary of Brazilian independence, there was a complete destruction of the hill motivated by a desire to ‘modernize and cleanse’ Brazil’s then-capital and make it ‘more European’. Thus, 100 years ago, one of the city’s first landmarks was demolished: Morro do Castelo, or Castle Hill.

The destruction of Morro do Castelo produced new outcasts in the city. Evictees—most of whom were from the lower social classes—were left to seek housing in informal tenements, peripheries or hillside squats, especially in Centro and the North Zone. This process was part of a pattern observed throughout the 20th century of self-organization by the working classes to meet their needs neglected by the State. In the fight for housing, people created new ways of inhabiting and living in the city. The favela is one of these solutions.

From City Landmark to Landmark of Backwardness

Initially this hill in the center of Rio was called Morro do Descanso, or Restful Hill, due to the difficulty of its conquest and colonization. Home to one of the main Portuguese forts on the Guanabara Bay, the São Tiago de Misericórdia Fort, Morro do Castelo was fundamental in defending against foreign invasions, as well as being the second and definitive birthplace of the city’s creation and center point from which the urban occupation of Rio radiated outward. Its golden era, however, ended in ruins. You could say that despite not being the first or the last hill demolition in Rio, the dismantling of Castelo shaped the urbanization of Rio in the 20th century.

“They’ve brought a large and old hill down and a new city, a white city, has emerged—this is what future chroniclers of Rio de Janeiro will be saying in a few years time about the year of grace that is 1922. The old Castelo agonizes… Little by little it slips away from land to sea and a new city, all white like a virgin, quickly starts to appear on the still disgusting, red, giant dump. From the enormous dying hump enters a bleeding neighborhood, like a monstrous birthing, as the elements of existence of the new city emerge!… We will then have a white city. The city of the future. Not the city of the future—or better, futurist city—as conceived in the fantastical imagination of American engineers… No. The white city won’t be a North American city. It’ll be a pure and simply Brazilian city… And alongside the old, decrepit, exhausted city, which thought with an unconnected brain, always imitating the institutions of others… next to the old, ignorant, and pretentious city that drinks tea at five o’clock because that’s what they do in London, with nonchalant airs because that’s what Paris orders… comes the white and Brazilian city! There’s much to hope for from it! And with it comes a new era!… 1922 is both a date and a milestone.” — Benjamim Costallat

In the above excerpt from the chronicle The White City, Benjamim Costallat critiques the destruction of the city’s birthplace, the lack of thought from the nation’s political leaders, as well as discomfort with the idea of cleansing Rio’s central region where black, poor, and favela residents lived. Costallat evidences that the urban problem goes beyond that of housing and circulating in the city. The fashion was to establish a new model of civilization. According to Costallat, the destruction of Morro do Castelo was the result of a perceived need to erase the past in the attempt to achieve this model. Despite being the largest and best known hill to be destroyed in Rio’s downtown, others had the same fate, like Morro do Senado which today is the Praça da Cruz Vermelha (Red Cross Square).

The city of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro—the original name for the city of Rio—has an indelible topography of hills and swamps that is recognized worldwide. Situated between the sea and the hillsides which were home to the first inhabitants and shaped the arrival of new ones, over the centuries the landscape was re-signified with the hillsides and lower areas transformed into frontiers of discrimination and racial, economic, and social hierarchy.

The city was founded in 1565 on Morro Cara de Cão at the mouth of the Guanabara Bay next to Morro da Urca. The second and definitive installation in the city occurred in 1567 at the top of Morro do Castelo, a strategic point for maintaining Portuguese rule. The new seat of the city was chosen as the hill faced Villegagnon Island where a French colony threatened Portuguese dominion of the city. Morro do Castelo was strategic for structuring a firm defense in case of new invasion attempts.

For centuries, the city of Rio de Janeiro was extremely important for the development of the Portuguese colony. The arrival of the royal family in 1808 consolidated once and for all Rio’s central role in the administration, politics, and culture of the Portuguese Empire. Brazil went from being an important trading hub, colony, and port trading in enslaved peoples, to a kingdom equal in status to Portugal. Rio de Janeiro became the capital of the Portuguese Empire and later, from 1815, of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. From 1808 to the Liberal Revolution of Porto (1920-1821), Rio de Janeiro was the only European capital outside continental Europe. Whether as a capital of the colony, Portuguese Empire, Brazilian Empire, or Republic of Brazil, Morro do Castelo had been a strategic point and the heart of the city since the 16th century.

In the 1920s, the Brazilian population experienced a period of great effervescence and change in the urban landscape, especially in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s then-capital. The attempt to erase the colonial image combined with the longing to transform Rio into a “Paris of the Tropics” fostered physical changes such as the demolition of hills, tenement houses, and buildings that were at odds with the capital’s new, European image. It was at this time, in an attempt to erase the colonial and backwards image of the country, that Morro do Castelo was once again seen as a strategic element in the city’s plans for the future.

The peak of this process occurred during the administration of Rodrigues Alves (1902-1906), president of the Republic, and of engineer Francisco Pereira Passos (1902-1906), mayor of Rio de Janeiro, appointed by the president to the role. Both have been enshrined in history for the drastic interventions they oversaw across Rio’s urban landscape inspired by the modernization of Paris realized by Georges-Eugène Haussmann and Napoleon III. The Alves-Pereira Passos era saw the construction of Avenida Central (today Avenida Rio Branco), the National Library, Municipal Theater, National Museum of Fine Arts, and more. The Passos government became known for “knocking it down,” as hundreds of constructions, historic buildings, and homes were destroyed during the modernization process.

In this context, the occupations, informal settlements, tenements, and favelas were understood as urban problems and social maladjustments. Their inhabitants—poor and black people—inherited the stigma held by the elites of being the dangerous class. Thus, the favela, present in the Rio urban scene for at least two decades by 1922, was seen as a target of repression, control, and cleansing—the only public policies aimed at these spaces.

The racist, eugenic, cleansing ideas propagated by newspapers in the 19th century were based on the notion of progress that shaped various European countries in the 19th and 20th centuries. According to these theories, Brazil needed to be “improved” through racial refinement by encouraging European immigration so as to purify the Brazilian race of its indigenous and African elements. It was understood that this “regeneration” would occur through whitening, mixing, and cleansing public policies aimed at instilling new habits in the population.

As a city previously ravaged by a series of epidemics, cleansing perspectives ran through the authorities’ and Rio elites’ discourse and was used as justification to remove tenements in the center of Rio de Janeiro. In this period, various public health figures pointed to the need to remove hills, infill swamps, widen roads, and apply codes of civil conduct as public health measures. The cleansing focused on blaming the poor and their housing for the unsanitary conditions in cities and the spread of diseases.

Urban Cleansing, Morro do Castelo, and the 1922 World Expo

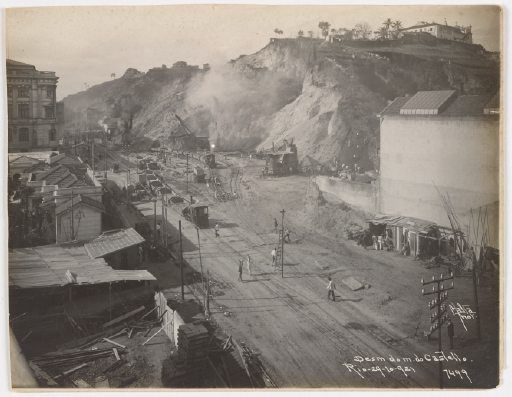

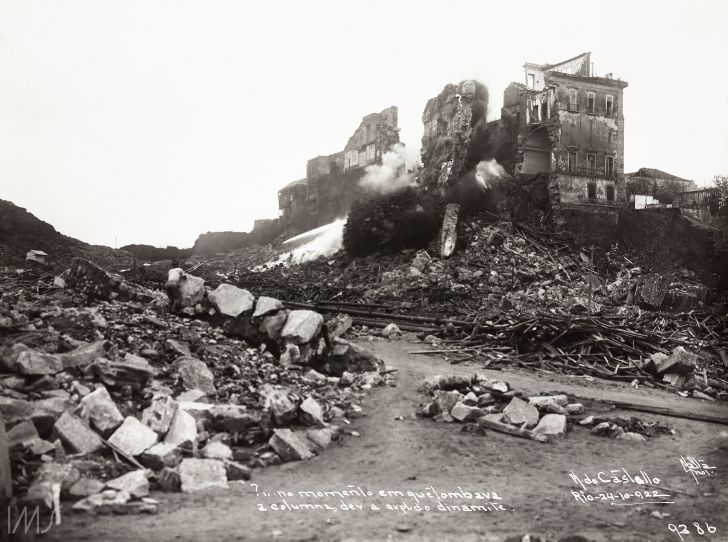

In 1922, the commemoration of the centenary of Brazilian independence brought to the fore the idea of transforming Rio de Janeiro into a model of national progress. To prove its modernity and capacity for achievement to the world, the Brazilian and Rio governments decided to organize a World Expo as an event to celebrate 100 years of independence. Morro do Castelo was destroyed with the pretext of making room for the universal exposition, with hoes, explosions, and powerful water jets.

“President Epitácio Pessoa (1919-1922) decided to hold a World Expo to mark the occasion and present Brazil as a modern, civilized republic to the world… The model for the ambitious project was the European international expositions of the 19th century, in particular those in London (1851, 1862) and Paris (1878, 1889). In this context, the host country received exhibiting nations, presented its national production, and above all showcased the State capacity to modify the urban space on the international stage. Traditionally these expositions featured radical transformations in cities: opening avenues, transposition of rivers and lakes, infilling, etc. A key moment for the modernization of Brazil.” — Flávio Moraes

In 1921, over 5,000 people lived on Morro do Castelo. Even the groups who defended the permanence of the hill, such as newspaper Jornal do Brasil, only highlighted the historical value of the locale and the need to conserve traditional architecture. The right to housing wasn’t discussed, except in the case of writer Lima Barreto in his chronicle Megalomania, published by Revista Careta in 1920.

Records of Morro do Castelo Demolition and the Photography of Augusto Malta

Augusto Malta (1864-1957), a photographer from the state of Alagoas, was the main documenter of Rio de Janeiro’s urbanization in the first three decades of the 20th century—a period of rapid and traumatic modernization. His photographs provide spaces of memory where one can witness the contradictions inherent in modernizing a city by observing its past. Malta started work in 1900 and was named the City of Rio’s official photographer in 1903, a role created to document the progress of Pereira Passos’ enormous project. For over 30 years, he documented the grand events and more everyday aspects of city life.

Malta documented constructions, demolitions, interventions in public spaces, squares, and historic buildings, as well as the city’s people. His photos were used in the first illustrated publications such as magazines Fon-Fon and Careta and for postcards. Flávio Moraes, social scientist and filmmaker, shared in an interview part of the research for the project The Universal Exposition through the Photography of Augusto Malta, exhibited by the Museum of Image and Sound in 2022:

“Malta documented those expelled from the center of the city: their homes, habits, and mainly the poverty that followed shortly after the abolition process. These records were used as scientific proof of the unsanitary conditions of the houses to be removed. Those excluded from the modernization of Rio de Janeiro—those that went up the hills in the South Zone or to the suburbs for housing—were the same people who constructed buildings and removed entire hills in the center of the Federal District.” — Flávio Moraes

Rio’s history and the history of Brazil have always been intrinsically linked, including in the way the occupation of land occurred: from the city as a point guaranteeing Portuguese rule; as the main port of entry for enslaved people well into the 19th century; in the strategic importance of the Guanabara Bay for sea routes, contributing to maritime trading and wealth accumulation which, centuries later, allowed the structuring of the web of power and economic accumulation in the city.

“Mayor Carlos Sampaio compared Morro do Castelo to a decaying tooth in the Guanabara Bay’s beautiful mouth. With the area’s demotion, the city lost various historical assets: the São Sebastião Church, the Jesuit School, the Casa dos Pretos (where Afro-Brazilian religious rituals took place), the Clock Tower, and Astronomical Observatory. The demolition works were financed by a European bank and ended up costing much more than anticipated. In order to resolve the overspend, Sampaio took out new loans with foreign banks and left the city with huge debts. At the same time, the mayor was accused of corruption because he was a shareholder in the company which received the contract to demolish the hill.” — Flávio Moraes

Morro do Castelo exerted its presence and importance in Brazil’s and Rio’s history over centuries. In an apparent contradiction, it was in the name of development and attending to political and economic interests that the hill was geographically eliminated from the landscape in 1922.

The First and Last: What Remains of Morro do Castelo

The Ladeira da Misericórdia street in the center of Rio was one of the first open roads for those who climbed the hill from the bottom, dating from the beginning of the city’s colonization. Morro do Castelo’s first street was also the only part of the hill not destroyed. A small section was preserved. It currently occupies a small part of the sidewalk next to the Our Lady of Bonsucesso Church and the Santa Casa da Misericórdia Hospital. In 2017 it was granted listed status in a decree by IPHAN due to its importance as a relic of the predatory and rapid urbanization of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

As well as the Ladeira da Misericórdia, Morro do Castelo remains in the Rio landscape as the namesake for the area where the hill was once located—between Avenida Rio Branco, Santa Casa de Misericórdia Hospital, Praça XV, and the Santa Luzia Church today. The area continues to be known as Castelo. Those who know nothing of the history of this historic landmark erased from downtown Rio’s geography revive its memory in the everyday life of the city: the buses that go to this region have Castelo as their destination, the hill that no longer exists.

About the authors:

Antônio Bispo is a historian with a degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s History Institute. He holds a Masters degree in Comparative History from PPGHC-UFRJ and is working on a PhD in Urban and Regional Planning at IPPUR-UFRJ.

Arthur Peluso is a documentary photographer and historian with a degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s History Institute. He is working on a Masters degree in Urban and Regional Planning at IPPUR-UFRJ.

Flávio Moraes is a social scientist with a Masters degree in Comparative History from PPGHC-UFRJ and is working on a Masters in Cinema and Film at the Fluminense Federal University in Niterói.

Mayara Tosta is a historian with a degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s History Institute. She is working on a Masters degree in Urban and Regional Planning at IPPUR-UFRJ.

Wladimir Valladares is an educator and public administrator with a degree from the Fluminense Federal University. He is a specialist in public management and is working on a Masters degree in Urban and Regional Planning at IPPUR-UFRJ.

Barbara Gigante is a public manager with a degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. She is working on a Masters degree in Urban and Regional Planning at IPPUR-UFRJ.