The revision of a city’s master plan concerns all its inhabitants. As the main urban planning law at the municipal level, Rio de Janeiro’s Master Plan will guide the city’s development for ten years, establishing growth parameters, zoning regulations, land use policy and urban policy goals, as well as the mechanisms to achieve them. Though it can seem like a discussion limited to technical professionals, distant from everyday citizens, a master plan directly affects the lives of all city residents. As such, public participation must be one of the fundamental pillars of the process. When the law is revised every ten years, all of society should be invited to participate and discuss the city’s challenges, interests from different sectors, and solutions for how to improve daily life. A broad spectrum of perspectives and interests should be taken into consideration in the plan’s final framework.

The revision of Rio de Janeiro’s Master Plan began in 2019 and was interrupted by the pandemic. Though still a fragile time in the health crisis, the executive branch—City Hall—chose to resume discussions in 2021 and formed online working groups with civil society organizations and government professionals to develop proposals for revising the Master Plan. The process was criticized for the tight schedule and a limited number of public hearings proposed by City Hall. Minimal space for public participation is not compatible with the development of legislation which will dictate a city’s development standards for ten years. Despite this, the draft bill was hastily finalized by the Municipal Urban Planning Secretariat and sent to the legislative branch—City Council—at the end of 2021.

Once the plan was in the hands of City Council, more space was granted for public participation. During this phase, 26 public hearings were held to discuss the Master Plan draft bill in 2022, with 17 held in diverse regions of the city. The document was discussed with different sectors of society, who put forward their positions and defended their interests. There was a greater possibility for people to voice their issues, though there still wasn’t clarity over which demands were listened to and taken into consideration.

Suddenly, in November 2022, City Hall sent 215 amendments to the Master Plan draft bill—the document the City itself had drafted—back to the City Council. The vote on the bill had been scheduled to happen in November, several days after the large number of amendments were abruptly presented, not leaving enough time to discuss them with the public. The rush to approve the bill and lack of clarity over what motivated the amendments caused strong reactions from some sectors of society, which demanded more transparency from the executive branch. The generic justification given was that the proposed changes were a mere refining of the text and not substantial alterations. Furthermore, according to City Hall, the changes responded to society’s demands that had emerged from public hearings.

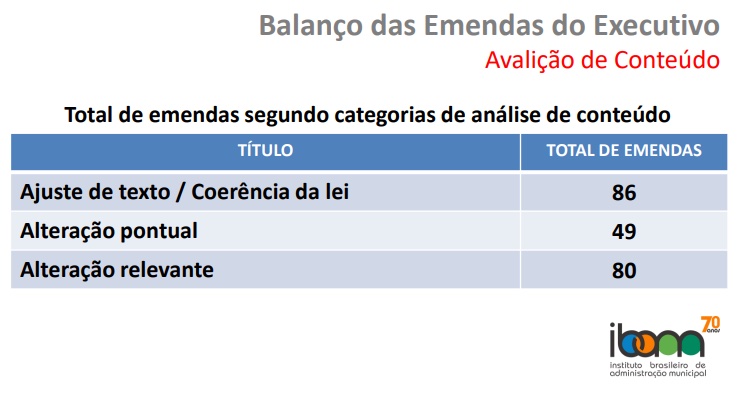

However, what happened in practice was quite different. According to a survey by IBAM—the agency responsible for advising City Council on its master plan—80 of the 215 amendments represent a significant alteration to the bill. Some introduce new urban design parameters, others modify procedures, and some completely erase mechanisms laid out in the bill. Far from merely adjusting the text, the changes were so substantial that the Council scheduled seven new public hearings to discuss them with the public. After years of discussing the city’s updated master plan in a process City Hall claims was participatory, we see an attempt to significantly reformulate the bill in the final revision stages, without any transparency or concern with justifying the changes to people who have dedicated their time and effort to collectively build a master plan that responds to the interests of all.

Concerning the argument of adapting the document to public demands brought during hearings, there was no indication of which public statements were being addressed and when or by what means they were presented. In fact, it appears that public participation was used as a pretext by which the executive branch introduced changes that serve their interests, under the guise of having listened to the public. A telling example of this is the complete removal of a new legal instrument for guaranteeing housing in the city: the Community Land Trust.

The Community Land Trust (CLT) is a model of collective land management characterized by separating land ownership (collective) and building ownership (individual). The arrangement allows a balance between individual and collective interests and ensures the model’s central objectives: guaranteeing communities can remain where they are, maintaining affordable housing, and promoting resident-led development. With over 50 years of success and applications in over a dozen countries, the CLT is widely recognized as a powerful tool for fulfilling the right to affordable housing. In 2017 it was included in the New Urban Agenda (item 107)—a UN document which establishes global guidelines for good urban governance—as a sustainable and inclusive housing model that should be encouraged by signatory states, including Brazil.

The CLT was widely discussed during the revision of Rio de Janeiro’s Master Plan, both in the working groups organized by the executive branch and later in City Council hearings. The diverse responses from across civil society were positive, recognizing the importance of including this innovative mechanism in the master plan, due to a progressive movement pushing for new approaches to the challenges of housing in the city. It would align with the moves of other cities which have been discussing the model, such as the neighboring municipality of São João de Meriti which recently approved the CLT in its Master Plan.

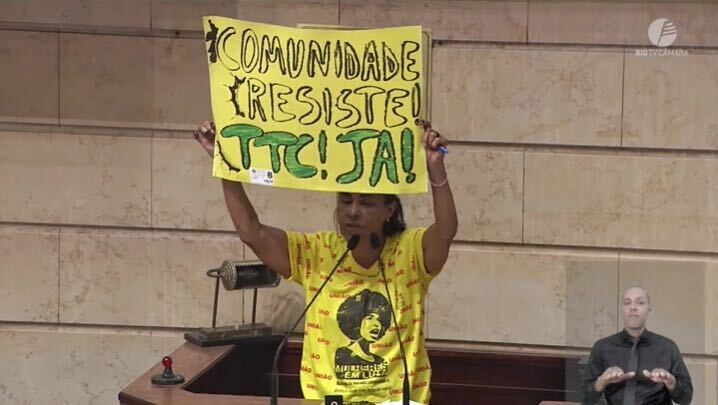

Over the course of numerous public hearings, a range of sectors of society supported the approval of the Community Land Trust as a recommended instrument in the master plan, with no opposition. Including the CLT as a tool within the city’s urban policy toolkit is a social demand. This was made explicit in an open letter to elected officials in support of the instrument’s adoption signed by 49 civil society organizations historically involved in the fight for the right to housing and the city. There was a broad mobilization by society to defend maintaining the CLT in the new master plan at a recent public hearing on April 5. Over 100 residents and community leaders filled the City Council chambers to demand mechanisms which protect communities from eviction and gentrification.

However, City Hall, led by Mayor Eduardo Paes, continues to maintain the position of excluding this innovative provision for ensuring affordable housing for low-income families in the city, without presenting any justification. On reading amendment #182, which removed the Community Land Trust from Rio’s Master Plan, the justification given was the need to “refine the text.” This is far from a legitimate explanation for such a significant change to the plan and shows the City’s disregard for people’s pleas. The total lack of transparency from the City regarding its over 200 introduced amendments goes in opposition to the principle of public participation as a pillar of urban policy, as stipulated in the Brazilian Constitution and the City Statute.

The CLT’s removal is far from the only significant change to the Master Plan. Among other new proposals by the executive branch, there is a drastic change to the Outorga Onerosa do Direito de Construir (OODC), in English known as “onerous grants and the transfer of the right to construct,” an instrument with the potential to significantly increase the City’s revenues by way of an offset charge for real estate ventures. It works by establishing a basic coefficient for the use of land, within which new ventures can build without additional cost. Any building which exceeds this coefficient must request a concession from City Hall by paying financial compensation. Previously considered an instrument for general application in the city, the amendments create various exceptions for its application, totally reversing its central logic. Furthermore, they impose a waiver of the charge in the first five years of the bill’s term, leaving an uncertain situation and limiting the instrument’s revenue potential by exclusively serving the demands of the real estate sector—those that would be mainly impacted by the charge. The main demand from civil society presented at the hearings about the instrument concerned allocating the funds collected to social housing and urban development. This is not addressed in the amendment, showing yet another serious disregard for the public’s demands.

Given these and other structural changes to the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan draft bill sent without any participation or justifications, it is clear that City Hall’s positioning threatens effective democratic processes. Social participation is not merely a formal detail, an inconvenience that government can simulate and cross off a list. It is a constitutional requirement and collective right. Much more than listening to people’s demands, the authorities need to take them on or at least give a transparent response as to why they are denied. Otherwise, Rio will continue to produce a centralized urban policy that is far from meeting the needs of its citizens. This seems to be what some wish for in the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan.