Clique aqui para Português

This article is based on a conversation with Yves Cabannes, Professor Emeritus at University College London (UCL), advisor to the Mutirão 50 Project, which began in the late 1980s in Fortaleza, capital of the northeastern Brazilian state of Ceará. The conversation was transcribed and supplemented by Cabannes, with additional commentary and information contained in the document Do Mutirão 50 ao Residencial Nova Alvorada.

The Mutirão 50 (Collective Action 50) project began in the late 1980s with the struggle for housing led by a movement of unsheltered people in the peripheries of Fortaleza, capital of the Brazilian state of Ceará. At the time, a new favela was being settled every month, built through land occupation processes.

By the end of the decade, Fortaleza municipal government’s Community Action Unit (UAC), in partnership with the landless movement, registered 550 families in a favela called Conjunto Marechal Rondon. Most of its inhabitants had been forcibly evicted from Avenida Beira-Mar during the military dictatorship to make way for the construction of luxury hotels and apartments. Many of the displaced families. who were already living below the poverty line, experienced a new reality marked by acute hunger and glaring housing needs.

It was in this context that, in 1988, the Mutirão 50 Project was born through a partnership between multiple actors: the Fortaleza municipal government—administered at the time by the Workers’ Party (PT) which established a close relationship with social movements such as the local Landless Movement (Movimento dos Sem Terra, or MST), the UAC (which was part of the city’s Social Service Foundation), the local landless movement, primarily the families they had selected, and the Research and Technological Exchange Group (or GRET), an NGO that provided technical assistance to social movements.

Resources were varied: the municipal government of Fortaleza donated one hectare of public land; the municipal and state governments provided basic infrastructure: water, sanitation, electricity, and drainage; funds for building materials were attained through international aid; and the building itself was done through the collective action of participating families, who worked an average of twenty hours per week.

The aim of the project went beyond building homes. It was to create “a piece of city,” a micro-urban district with houses collectively-built through a mutual aid process, under its Brazilian specificities called mutirão. The project also created back and front yards, small squares and plazas, public open spaces, small shops, a daycare center to support women looking for work or who were already working, community gardens, and a small industrial area. All the buildings were constructed by residents themselves, through mutual aid.

The land donated by the city government to the project in the Marechal Rondon favela was previously a flood-prone waste dumping site, which made construction extremely challenging (see photo 2). Ground was broken there nevertheless, since it was close to where the families had been living, and this proximity was important to allow for voluntary work. Out of the 550 registered families by the Landless Movement, 50 were selected for the first phase based on social criteria that took into consideration the severity of their poverty and their willingness to commit to the project’s ambitious objectives. Organizing labor through a community-based mutual aid system of construction was complex, as some of the selected participants were elderly women living by themselves and unable to directly engage in construction works. There were also a number of large families with children, who wanted to play constantly on the construction site, which created a safety risk and slowed the building process. To by-pass these difficulties, it was decided that those who were unable to work onsite would be in charge of the kids and preparing collective meals, a highly valued task in a context of acute hunger.

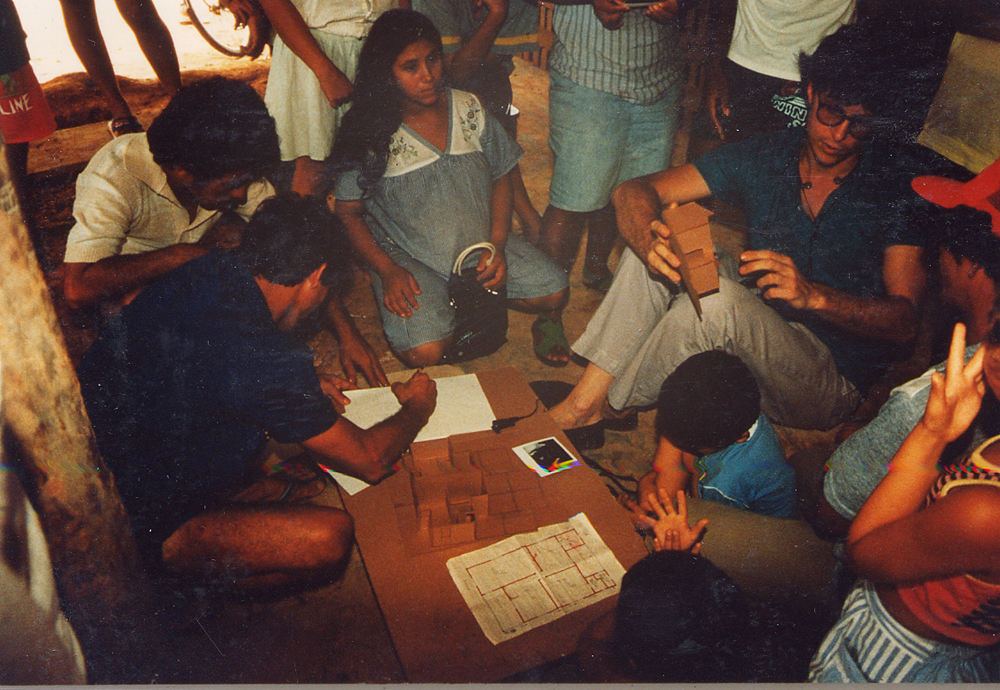

At the request of the families—in particular the women—the construction process did not start with homes, as originally envisioned. Instead, a shed for productive activities was built first, using materials available locally like carnaúba [a type of oil palm], trunks for its structure and palm leaves for roofing. The walls were made of compressed soil cement blocks, using earth available on the site. The rationale to start with producing building components instead of building the houses with conventional materials available on the market reflected the aspiration of women to get some training to be able at a later stage to find jobs and generate income.

Starting with building the production shed allowed for testing construction methods and initiating the production of compressed cement soil bricks, window sills, stone-cement blocks for the foundation, individual water tanks made of ferrocement, and toilets made from cement and stone dust (as shown in photos 4 and 7). The space became a training and learning center for the families and helped reduce construction costs, allowing residents to plan and ultimately build larger homes consisting of two bedrooms, a living room, a bathroom, and an exterior washing area with a sink.

As the process moved forward, the future residents created the People’s Council of Rondon (CONPOR). The organization was responsible for keeping residents informed, mobilizing families, organizing the collective work, as well as liaising and mediating with city government in tense situations. It was also responsible for formulating internal rules and guidelines, with the help of the UAC.

In 1989, before leaving office, the city government agreed to donate the land under a collective regime to CONPOR, marking an important milestone in the history of the housing struggle in Brazil. After ample discussion between CONPOR and the families, this collective property was divided into two forms of property and usage rights: each family would sign an individual use contract for their home and plot of land called a contrato real de uso (concession of use title), among the legal possibilities of the time; while the rest of the land would be designated for collective use.

The micro industrial district, shops, daycare center, squares, and streets became the property of CONPOR. The experience bears similarities with the Community Land Trust (CLT) model—known as Termo Territorial Coletivo in Portuguese and which has been introduced in Brazil since 2018. The micro district was also inspired by the first English Garden City, Letchworth, which is still in existence today.

The first 46 homes were delivered to the families by the end of 1990. At that time, the families and CONPOR changed the name of the “Mutirão 50” housing development to Residencial Nova Alvorada (New Dawn Residential Estate), which attempted to symbolically encapsulate the feeling of living a dignified life in a small urban neighborhood.

It is important to note that the completion of the homes and the provision of basic services were realized under a new city administration by the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB),

headed by Ciro Gomes. This was a party that operated in opposition to the Workers Party [PT], which had started the project. Thus, one of the most important victories of the Mutirão 50 project was its capacity to maintain collaborations with different municipal administrations led by conflicting political parties (PT, PSDB, and the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party or PMDB) and its commitment to continue its work. This was made possible thanks to the permanent mobilization and unity of the families, their advisors, and the city government’s technical staff. Maintaining such collaboration through time, despite political changes in the government, was a key to the success of this innovative housing project in Ceará and helped guarantee its continuity.

Decades Later, Some Reflections about the Mutirão 50 Experience

According to Yves Cabannes, there are four key aspects of the Mutirão 50 experience that are worth emphasizing:

1 – Residents’ Mobilization

Resident mobilization had its highs and lows during the mutual aid building process. Many families quit because of delays in finalizing the project and the complicated transitions between governments. In addition, the evangelical movement entered Conjunto Rondon with proposals that did not support the participation of families in the collective effort toward building a common good. The evangelicals’ message of individual salvation and creating a more direct relationship with the church conflicted with the Mutirão 50 strategy of collective improvement, which ultimately led many families to lose their motivation to move forward. However, it was interesting to observe there was one evangelical family who remained highly active in the collective effort all the way through moving into their home, demonstrating that CONPOR was open to diverse religions among the families, including Catholics, Protestants, and Afro-Brazilians or Syncretists.

Despite difficulties and some families dropping out, the landless waiting list was long and it wasn’t hard to find new families wanting to join the project. Community organizing, training and capacity building of the newcomers was challenging, as it meant starting again from scratch. The hardest lesson born from the experience was that it is a must to start out such projects with a larger number of families to make sure there will be enough to finish the project.

Given the presence of chronic hunger, participating in the mutual aid construction process (see photo 4) was an opportunity for many families to access food in the first place. During construction, the struggle to feed people who were involved was taken on primarily by the women, who mobilized to prepare meals by negotiating with stores, construction materials providers, and industrial meatpackers to obtain free food. This illustrates the importance of taking into consideration the immediate needs of residents as an integral part of a long-term social project.

Despite these challenges, the organization and strength of CONPOR kept the project going. Participating families were reorganized and others who had been on the waiting list provided continuity for the construction. No one knew whose house they were building—their own or someone else’s—and in the end homes were distributed according to who contributed the most hours of labor to the collective. According to Cabannes, the entire process created a strong feeling of belonging to their new neighborhood and strong bonds among the residents:

“The Mutirão 50 families stayed put and very few sold their homes, which is different from what has happened in other mutual aid housing projects. This was because the whole effort was a collective social housing production process, which made people feel they were a part of it. The desire to stay and not sell, in spite of their poverty and multiple needs, was extraordinary. And that was a paramount lesson we learned. It wasn’t just collective strength; the mutual aid construction process itself provided a sense of ownership.”

2 – Women’s Participation

The second point Cabannes highlights is that the participation of women in the Mutirão 50 project was decisive for its completion. Women were the most active participants and in general their work was more consistent and effective (photos 5 and 6). They were responsible for leading the process and adapting the original home construction plans, prioritizing the building of facilities that would generate work and income. In his words:

“The women that led the Mutirão 50 project said that they didn’t just want a home, they also wanted jobs. The issue of employment was a big concern and began with the production of soil cement bricks (see photo 4) that valued available local materials. The production workshop (see photo 1) was built in the initial phase and was the result of the women’s labor, who set the example and steered the process. This was a great lesson…

Basically, the project wasn’t just about generating conventional jobs. Rather, it contributed to the creation of a social economic model. Skills training courses were offered in the first workshop the project provided, training people in the production of building materials and components that would be used to build their homes. Community land ownership also generated employment in other ways: it allowed the project’s participants to build productive spaces, including the micro industrial district, where there were a variety of small businesses, ten shops around the square, and a the day-care centre. The project opened up an opportunity to young women and teenagers from Mutirão 50, as well as from the rest of the Conjunto Marechal Rondon favela, in finding their first job. All of these spaces generated social and economic inclusion in the first place.”

3 – Employment and Income Generation

The third aspect is precisely employment and income generation. Due to a strong demand from the families, and given the socio-economic situation they found themselves in as surveyed by technical staff and advisors, income generation became a central objective of the Mutirão 50 project. Cabannes explains:

“Hunger was the central problem, not just the lack of housing. For this reason, we decided that for every two houses, we needed to generate one job. This happened a lot in the Comunidades program, which allowed us to scale up the Mutirão 50 project with the objective of collectively building 1,000 homes through mutual aid in the metropolitan region of Fortaleza. We were obsessed with generating employment so as to reinforce people’s economic independence, and we managed to go beyond expectations. Creating housing wasn’t an end in itself; it was also a means for skill training, so much so that before the homes were finished, CONPOR was formed as a civil construction cooperative, the first of its kind in the Northeast region.”

4 – The Issue of Land Use and Ownership

The fourth and final aspect was the issue of land ownership. Cabannes emphasizes that the whole Mutirão 50 process was the result of the mobilization and struggle of families from the local Landless Movement, along with other social movements and institutional partners. However, government support was also extremely important. The project was carried out on municipal land, which was later transferred to CONPOR, meaning that the city donated the land to an entity formed by local residents. The land thus became community-owned, managed and used.

In 1990, the Peoples Council of Rondon, CONPOR, initiated the process of legally transferring the right to use individual plots of land to residents. This, in effect, created a hybrid arrangement between collective ownership, which represented most of the land, and individualizing the plots of land on which the homes were built through contracts that granted the right to use that land.

This arrangement was made possible thanks to the collective management of the land.

Cabannes also comments that given the lack of legal precedent regarding this type of land arrangement, there was some confusion around issues of responsibility, for example who would be tasked with road weeding, street cleaning, garbage collection, public lighting, etc.

“The authorities’ first reaction was to say that the land was private property, more like a gated community—albeit one with collective ownership—and therefore the city government couldn’t intervene. We could not find any legal precedents or jurisprudence to refer to, except for legal rules regarding the private ownership of condominiums. Finally, after much mobilization and negotiation, it was decided that public services would be provided by the municipality. We had never thought about this, as our priority was to build homes, to finish the upgrading project, and to solve the question of land ownership. In reality, bringing in public services like the electrical grid, sanitation, and water supply up to each individual meter had to be a public service. To achieve this, we had to learn to negotiate step by step, for example, to reduce the width of the streets to allow a larger backyard for each house, like in garden cities and quite popular in vernacular urban architecture in the region… In the end, the authorities collaborated significantly.”

Due to the continuing mobilization by residents and CONPOR leaders, work continued after construction of the first 46 homes. Little by little, six more homes were built as well as additional workshops in the micro industrial district, a daycare center, and the shops that became a small shopping center. The rent of these spaces was meant to partially feed a community savings fund, managed by the Community Housing Department created by CONPOR:

“In theory, another source of income for the community savings fund was the monthly payments made by the families over six years, which represented 10% of the value of the construction materials utilized to build their homes. However, this didn’t work very well. First and foremost, the families needed to sustain themselves economically, which meant it was necessary to create more and more jobs.”

In Cabannes’ view, Mutirão 50 yielded impressive results and was a very successful project, both in terms of collective ownership and self-management by the families. External financial contributions were quite limited in relation to what was achieved in Marechal Rondon. Years later, in 1996, the project won a United Nations award for best practices at the Habitat II Conference in Istanbul, Turkey. More details about the project were presented in a publication about successful housing practices in Brazil.

Many things have changed at the Nova Alvorada Residential Complex over the last 30 years. Collective management worked well for many years, but later faced challenges resulting from decreased mobilization and political disagreements. However, they were not the only factors explaining the changes that took place. The daycare centre, for example, was formerly administered by the City of Fortaleza. For many years, it wasn’t clear who had political and administrative control over the area called Conjunto Marechal Rondon where Mutirão 50 was located, either Fortaleza or the adjacent Caucaia municipality. This type of unclear control is not uncommon in fringe lands around expanding Brazilian and Latin American cities. In recent years the Nova Alvorada Residential Complex became part of the city of Caucaia. This change meant that the daycare center lost its management and funding and, therefore could not be maintained and was closed. Its future remains unclear.

Another significant change was that the first workshops and the micro industrial district, as well as the shops, were taken over by landless families, which illustrated the inability of public authorities to provide solutions to the glaring housing shortage in the poorest areas of the Fortaleza Metropolitan Region. Cabannes further comments:

“Probably, the most important change was that CONPOR was deactivated, and the community lost a lot of its strength. There are various reasons to explain this which warrant a deeper analysis. In our view, the problem wasn’t only the diminished mobilization of some families, but rather the transformation of the community they had built and a sense of exhaustion after many years of struggle. The lack of support from the UAC when Conjunto Marechal Rondon was switched to the city of Caucaia, and the lack of consistent support from GRET and also Cearah Periferia (another NGO that was a local partner) were also factors. There was another issue related to the land. CONPOR wasn’t able to pay the IPTU (property tax) for the collective part of the property, and the individual family lots with land use agreement contracts were never fully registered legally due a lack of financial resources. Unfortunately, there was a fiscal deficit which contributed to the deactivation of CONPOR.”

Dona Margarida, one of the most active leaders at the time, who still lives in Mutirão 50, explains: “all we have is a concession for the right to use the house, but there was nothing legalized in regard to the land.”

Despite all of this, the story of the Mutirão 50 experience illustrates the importance of the struggle for land rights, and for the continuous engagement of the community throughout the whole process—from the construction of the homes to participation in urban policy-making—as well as developing creative and sustainable solutions for community development and secure land ownership. It’s critical to introduce young people and new residents to the principles of struggling for adequate housing, and for lasting results.

Mutirão 50 continues to be a pioneering project and an important milestone in the history of the struggle for land rights in Brazil, especially since it was managed by the local landless movement through CONPOR. Land was donated to a collective through a community property regime that provided a solution to the housing problem, and at the same time allowed for generating community urban spaces with a daycare center, shops, productive spaces, etc. It’s important to remember that the radical stance taken by the mayor at the time, Maria Luisa Fontenele from the Workers Party, was decisive in transferring the land to the community. Her attitude was similar to that of Bernie Sanders in Burlington, Vermont, at around the same time, who facilitated the donation of public funds toward the creation of the Burlington Community Land Trust, which is known today as the Champlain Housing Trust and has grown into the largest community land trust in the United States.

The Mutirão 50 experience, with its successes and limitations, is a cause for reflection on the current struggle for Community Land Trusts in Brazil. It shows the viability of a land rights system under collective management by residents, as well as a division of property between the land (collective) and homes (individual).

Individual titles with contracts establishing use rights resemble the CLT system. The difference is that in Mutirão 50, most of the property was indivisible and collective and held by CONPOR in order to facilitate other kinds of construction, like the micro industrial district and daycare center, while the home lots were granted individual use concessions. The experience of the Mutirão 50 project showed that it is possible to achieve strong community development when there is a formal legal structure and continuous mobilization by residents. It demonstrates that even though the collective process is often slow and challenging, it is fundamental for strengthening community and achieving residents’ goals.

Translation note: A first translation of the text from Portuguese to English was realized by Fred Hanson in April 2023. It was then reviewed and edited by Yves Cabannes, with final touches carried out by John Emmeus Davis in May 2023.