This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on water issues and the LGBTQIAPN+ population in Rio’s favelas and in the Baixada Fluminense for RioOnWatch.

Bananas, greens, bell pepper, okra, scarlet eggplant, eggplant, maroon cucumber, chayote, zucchini, beetroot, carrot, arrowleaf elephant ear, sow thistle, leek, various herbs, corn, lettuce, watercress, cassava: all these foods are grown and sold by small-scale farmers with allotments and farms in an area known as the Vargens Region in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone. However, constant flooding and real estate speculation are putting the lives of residents, land workers, and organic agriculture in the region at risk.

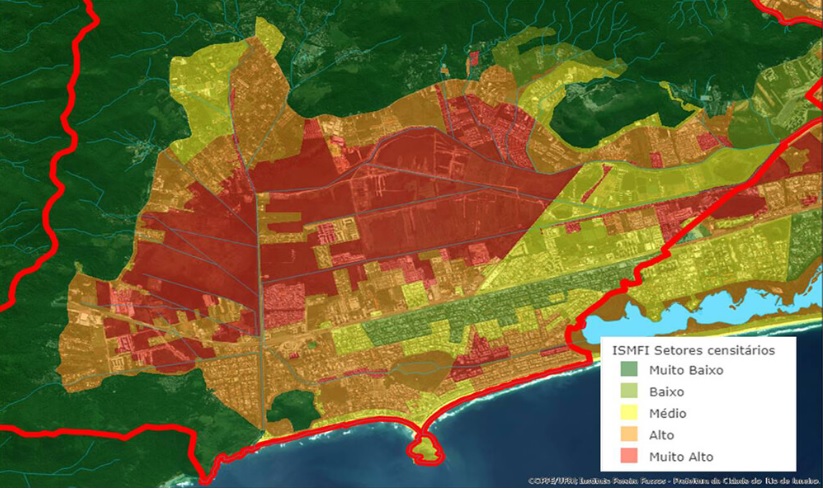

The Vargens Region covers the Camorim, Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Vargem Pequena and Vargem Grande neighborhoods and is located between the Pedra Branca State Park and Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex. Over 12,000 hectares in size, the Pedra Branca urban forest has dozens of water sources which flow into an area of four lagoons with running, fresh, brackish, or salt water known as the Pantanal Carioca (Rio Wetlands). This entire flooded and floodable area has been subject to drainage to open the floodgates to development.

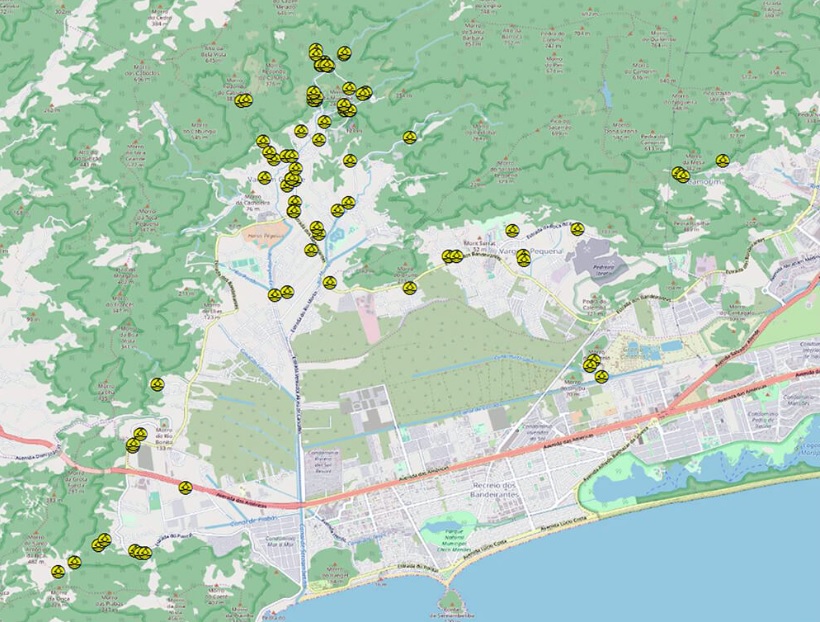

This has meant that rainwater no longer drains away into the areas it used to and that the biodiversity of the region has been attacked. It has also resulted in urbanized areas which flood in the rainy seasons, as happened in September 2020. At that time, residents filmed a video reporting irregular building work being carried out by the Chácaras Residential Club in Vargem Grande. Located in an environmental protection area, the building works blocked a river that ran there, preventing rainwater from flowing and creating a torrent on Estrada do Sacarrão. Resident of the region for over 30 years, environmental activist Beth Bezerra sounds an alert.

“Since 2021 City Hall has been dismantling [the region]. The Vargens Mosaic is being reduced with each decree. The last [decree] instituted the environmental zoning of the Sertão Carioca environmental protection area and proposed Conservation Units (UC), but with a 40% reduction in the area designated as the Campo de Sernambetiba Wildlife Refuge (REVIS). Landfills and dumps with waste from luxury real estate building works can be seen in the UCs. The result of this will be a heat island that impacts not just the water basin region but the city as a whole.” — Beth Bezerra

In an open letter, Bezerra highlights that Brazil is a signatory of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance which addresses the importance of wetlands of social interest aimed at conservation and the sustainable use of wetland ecosystems. She explains that as well as being an environmental protection area, the Sernambetiba REVIS receives all the rivers and channels coming down from the Pedra Branca Massif, functioning as a huge receptive basin for water flows, draining and distributing waters via channels.

Bezerra also points out that landfills, roads, and licensing within the REVIS area are putting some 20,000 families living on the stretch between Estrada dos Bandeirantes, the Portelo Channel, Rio Morto Channel, and the surrounding area, including favelas, gated communities, and land subdivisions, at risk.

Eduardo Ribeiro and his ten siblings are among these 20,000 families. The family owns a 16,800m² farm and has relied on agriculture for its livelihood for 70 years. Proponents of agroecology, with a focus on growing the most basic and resistant foodstuffs, the family farm produces all the fruits, greens, and vegetables mentioned at the start of this article. The farm used to send produce to the Rio de Janeiro State Supply Center (CEASA-RJ) and currently supplies various establishments in the region including restaurants, bars, grocery stores, and vegetable stands, as well as making home deliveries, as Ribeiro, who is also vice-president of the Vargem Grande Residents and Friends Association (AMAVAG), describes.

“Last year, we had half a meter of water in the plot where cassava, scarlet eggplant, and eggplant were being grown. I lost the whole harvest. Other producers lost everything too. Seu Jorge who grows greens on Sacarrão Road also lost everything. He was really discouraged, but thanks to support from other farmers in the region he managed to start growing again. My brother also got tremendously depressed because he lost everything and is now cleaning up the areas at the back and starting to plant cassava again.” — Eduardo Ribeiro

Ribeiro explains that his brother had to dig deeper ditches so that water coming down from the Pedra Branca State Park can drain away. He reports that a lot of water outlets have been filled or blocked by real estate developers in environmental conservation areas.

He reports that there are no incentives for local agricultural production from the city, state, or federal governments and highlights that farmers continue on their land producing food for the city thanks to the support network that has always existed among them. Throughout the conversation, Ribeiro recalled numerous landfills and building works over the last 30 years, so many that he has lost count. According to the Agricultural Census carried out by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2017, there are 87 produce establishments in the Vargens Region.

According to the article Social Struggles and the Role of Conservation Units published in Revista Periferias, some groups have remained connected to a past of struggles for ancestral lands, such as quilombos, while others have engaged with the fight for housing in favelas and against forced evictions, like Vila Autódromo. There are also those who farm, as is the case of Eduardo Ribeiro’s family. However, these can all be subject to gentrification processes. Geographer Brasiliano Vito Fico, author of the article, argues:

“The occupation of these areas is only possible when large interventions in the whole landscape allow for reduced risks to new inhabitants, especially in the floodable lower areas of the wetlands; installing expensive infrastructure to drain and fill the land requires a financial return compatible with the high investment from the civil construction market. This process will make it impossible for low-income populations to remain, leading to the inevitable gentrification of the Vargens.”

The Vargens Region is part of Rio de Janeiro City Planning Area 4 (AP4), made up of 19 neighborhoods in the city’s West Zone. AP4’s population grew from 909,955 in 2010 to an estimated 1,011,946 in 2015. The area started growing in the 1960s with the start of the Guanabara State urbanization plan in what was then the capital of Brazil. Commissioned to architect Lúcio Costa, the project involved the planned settlement of the AP4 region.

The idea was to balance built up areas with green areas and integrate the city’s North, South, and West Zones based on an expansive metropolitan perspective. According to the article Recent urban dynamics in the city of Rio de Janeiro: considerations based on data analysis of the IBGE census and municipal urban licensing by architect and urban planner Henrique Barandier, AP4 has experienced the largest population and housing increase in the city in recent decades. The population of AP4 grew 47.69% from 1980 to 1991, 29.59% from 1991 to 2000, and 33.33% from 2000 to 2010.

In the article Grassroots Resistance Protecting Rio’s Vargens Region, Beth Bezerra explains that the Vargens Region remained predominantly rural until the 1970s when there was a population boom with the surge of new land subdivisions, favelas, and gated communities.

Bezerra reports that social movements have always been part of the local pursuit for environmental preservation, housing rights, confronting the unbridled thirst of real estate forces, the right to water, and to education.

“Awareness of human rights has always been part of this history… Since AMAVAG was founded, from the Vargens People’s Plan to the S.O.S. Vargens Movement, grassroots participation has always had a voice, mainly in fighting the Vargens Urban Structuring Plan (PEU) and environmental destruction. Vargens residents are symbols of struggle and resilience, of remaining [in the territory], preserving what is essential in life for today and for the future. Grassroots movements have been part of this history since slavery. With the preservation of roots like the Quilombo Cafundá Astrogilda, small-scale farmers have helped feed the people of Rio since the 19th century, through sustainably grown produce supplied to markets and schools.” — Beth Bezerra

According to the Living Bay Movement newsletter, in 2022 Rio City Hall signed an agreement with Rio de Janeiro State’s Civil Construction Industry Union (Sinduscon-Rio) for the “development” of the Vargens Region with a project that plans river straightening, building of roads, bridges, and walkways, river dredging, and other huge “improvements” without any public consultation or the necessary environmental licenses. When asked about the project, the Municipal Urban Planning Secretariat (SMPU) responded by email:

“PLC nº 44/2021, which revises the Master Plan, sent by City Hall and approved by City Council in the first discussion, has medium and long term proposals of various scales to reduce flooding in the Vargens Region. Annex 1B outlines planned interventions for revitalizing, dredging, and improving the surrounding areas of various rivers and channels in the region. In the macro-zoning and zoning plans, there are restrictions on land occupation, implementing, for example, the requirement for Minimum Drainage Surfaces in the range of plots ensuring that part of the plot remains permeable. Green spaces and rain gardens are planned for the public spaces being upgraded as well, in order to help the flow of rainwater.”

SMPU also informed that it took part in public hearings for PLC nº 44/2021, both those organized by City Hall in 2021 and by Rio’s City Council in 2022 and 2023, to discuss the Master Plan proposals and actively listen to the demands of residents and local farmers in the Vargens Region.

The City’s Rio-Águas Foundation responded that it conducts periodic cleaning and silt removal of channels in the region with the aim of preventing floods and flooding:

“The Sernambetiba Channel, and rivers Cascalho, Vargem Grande, Vargem Pequena, Portão, Bonito, Calembá, and Cancela all receive cleaning services. The effects of the work has been felt this last summer with no records of significant flooding in these neighborhoods.”

For Beth Bezerra, the Conservation Units Sertão Carioca Environmental Protection Area and Campos de Sernambetiba Wildlife Refuge need to be created as the main role of these wetland areas is to function as a natural reservoir, retaining excess waters from rains and water courses coming down from the Pedra Branca Massif. The only way to guarantee occupation of the region is by respecting its land support capacity, which is fairly limited given the complexity and fragility of the local environment.

“Each time there is a flood in farmers’ plantations, there is a loss of at least R$500,000 (US$102, 525). And that’s just the agricultural produce! Floods mean other damages such as to motors, seedbeds, piping, hosepipes, materials, and soil. If you count all this, it’s well over R$500,000. These things take years to buy and set up [like, for example] an irrigation structure, that we lose in a few hours due to flooding. Thank God there weren’t any losses this year. What is happening now is a reflection of what happened long ago. Fighting against the system is difficult, it is the system which is controlling everything. We’re here fighting for our agriculture.” — Eduardo Ribeiro

About the author: Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Investigative Journalism. Working as an independent journalist and freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.