This is our latest article in a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on water issues and the LGBTQIAPN+ population in Rio’s favelas and in the Baixada Fluminense for RioOnWatch.

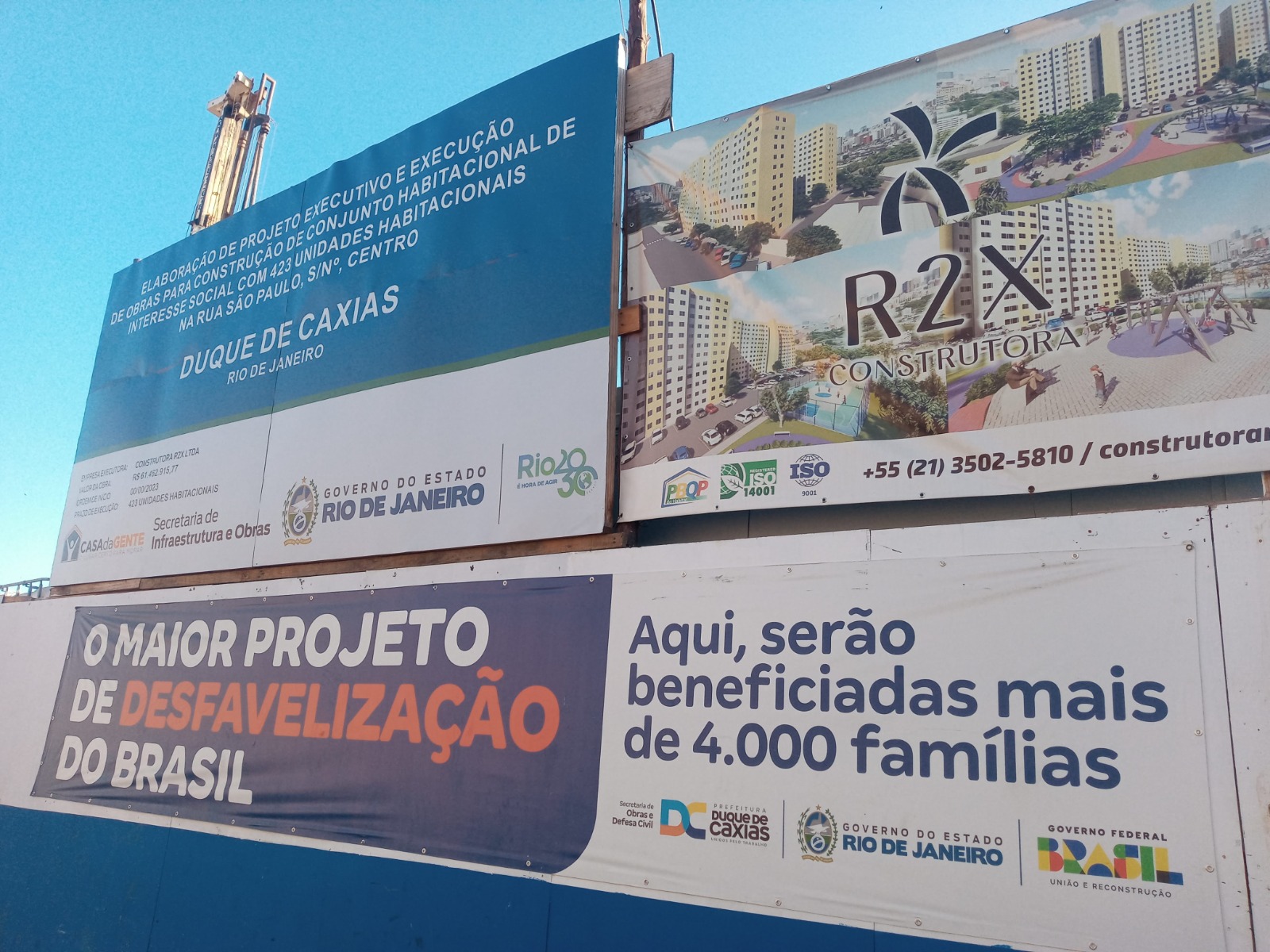

Residents of Favela do Lixão in downtown Duque de Caxias, in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region, have reported violations committed by City Hall during eviction processes that have grown in severity since 2020. In late 2021, some 60 families were caught off guard when the upgrading of three Favela do Lixão communities was announced under the policy of “defavelization” by City Hall, supposedly requiring their eviction from the area. The Vila Ideal, Parque Vila Nova, and Beira-Beira communities have existed for over 40 years and suffer government neglect and the structural lack of housing policies supporting Caxias’ economically vulnerable.

According to reports, attempts to remove Favela do Lixão began in 2013. However, the great anguish began on October 1, 2020. According to residents, Municipal Undersecretary of Upgrading and Housing Rafael Quaresma showed up with city officials and Military Police to demolish houses. They entered through a Favela do Lixão access point on Governador Leonel de Moura Brizola Avenue and used a backhoe.

Two months later, on Christmas Eve 2020, Caxias was hit by heavy rains. Five neighborhoods—Santa Cruz da Serra, Xerém, Parada Morabi, Morabi 2, and Imbariê—were completely submerged with flooding. The climatic phenomenon brought a terrifying deluge, although less intense in downtown Duque de Caxias. Just over two weeks later, on January 14, 2021, 58 families were caught off guard with an eviction notice sent by Caxias City Hall. Residents reported that municipal authorities went to their homes ordering everyone to leave in order to reduce the impacts of flooding in the region.

Unjust Compensation and Real Estate Speculation

Between one demolition and another, with around 150 homes already knocked down, setbacks and provisional agreements put forward by City Hall have generated insecurity and tensions in the area. At the beginning of the process Duque de Caxias City Hall calls “defavelization,” the municipality offered only three months social rent to residents, with installments in the amount of half a minimum wage salary (R$660 or US$134) each. The benefit payment was extended for the duration of the works, thanks to intervention by the Public Defender’s Office, which considered the negotiation unconstitutional in the manner it was being carried out by the government of Caxias.

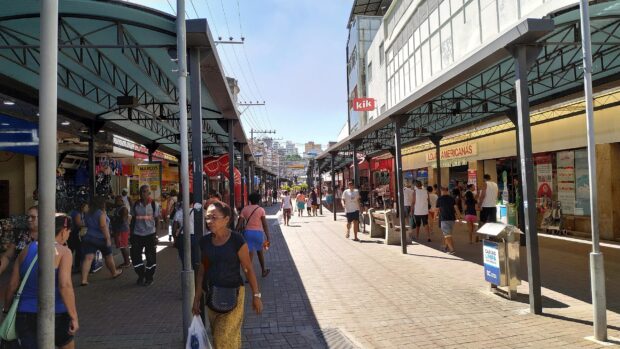

Favela do Lixão is very close to Calçadão de Caxias, a shopping hub, intercity bus station and an important commercial center in Caxias. According to the Municipal Secretariat for Urbanism and Housing (SHU) website, the aim is to offer “a new housing project with decent housing and guaranteed access to essential public services for the population,” including building a new daycare center, school, leisure area, as well as a basic health unit. However, it is clear that the location of the favela represents an attractive opportunity for real estate investment.

The local government states that Favela do Lixão is an invasion since the land belongs to the Brazilian Navy. This has been used as justification for overnight evictions. However, previous municipal administrations in the last 40 years have not prevented residents from developing the area. The decision to evict residents is seen as hypocritical, as describes Rose Silva, a community leader in the region.

“Forty years ago this was all swamp! We were the ones who did the infill. Then, [City Hall] put in asphalt, lampposts and street lighting. There’s a municipal school here! How can the City have the nerve to say that this is an invasion after all this time?” — Rose Silva

In this first phase, according to the SHU website, 800 families are being registered and transferred, with three options on offer. The first is an exchange in which the family swaps their property for an apartment in the future complex that will be built on the site. While the apartment blocks are under construction, families will receive social rent to pay for temporary housing. The second option is payment based on the value assessed for the buildings and other improvements that residents have built and occupied. The third is the so-called assisted purchase whereby residents find a property for sale with characteristics similar to the one they occupy. The City buys the property and offers it in exchange for residents’ current home.

That said, there are conflicts of interest and misinformation in each of the phases. In the second option, for example, the problem lies in disproportionately low values offered and defining the boundaries of buildings and improvements. In addition, some residents accept being moved far away to other districts of Duque de Caxias, such as Santa Cruz da Serra or Imbariê, according to activist and resident Gláucia Quirino.

“We don’t just have miserable living conditions here in the favela, no way! The City wants to pay the same amount for homes that are in a better state, that have a porcelain tiled wall or floor, for example, which is a pricier material, or even those with tempered glass, or two or more floors. These houses are sometimes 100m², but they only want to pay R$800 (US$163) per square meter as compensation when these houses are worth as much as R$100,000 (US$20,037). City inspectors say that residents are increasing the size of their homes after hearing about the prices to see if they can make more money. And on top of that, the apartments they want us to live in are 42m². I live in a house that is twice that size. This is all nonsense.” — Gláucia Quirino

Another example of the housing insecurity that hangs over residents of Lixão due to mismanagement by Duque de Caxias City Hall is experienced daily by seamstress Maria Neide. She was also part of the first generation that founded and built the favela over 40 years ago. The house where she lives now has a second floor, newly built after years of toil. However, City inspectors interpreted that the work was completed in a hurry so as to ensure a higher compensation. According to her calculations, the house should be valued at R$150,000 (US$30,693), but the city wants to close the purchase for R$52,000 (US$10,640). Neide was also pressured to move to the Santa Cruz da Serra neighborhood, but stated that since her sick elderly mother also lives in Favela do Lixão and needs her care, she would not feel comfortable leaving her community to live so far away.

“I paid for every brick here with my sweat. This was all mangrove swamps. I can’t just up and leave because I have a 91-year-old mother who needs me. I need to be with her twice a week, make sure she’s alright, give her the meds she needs. Living far from here would make life [even more] difficult for me.” — Maria Neide

Even local businesses which operate around the favela have not escaped the onslaughts by City Hall. Diego Tomás Fortes has a small building supply store on Piratini Street, which encircles the community. He says the amount offered by the city does not come close to what he spent buying the property a while back. There was no meeting with the public works secretariat. He says he had a conversation with a “city hall representative” about a month ago who started off “laying down figures,” which are being offered to all business owners. No one accepted, considering the unjust amounts.

“I paid R$120,000 (US$24,547) for the store, building it from scratch. But the City wants to lease it for less than half, around R$50,000 (US$10,231). This is completely disrespectful to us. They created these values based on a table that only they have.” — Diego Tomás Fortes

According to the Pacto RJ portal, a state-level version of the nationwide Transparency Portal, where information on all stages of construction is made available, 423 housing units and 12 commercial units will be built in Favela do Lixão at a cost of almost R$62 million (US$12.7 million). The services include the building site, earthwork, transportation, galleries, drainage systems and connections, foundations, structure, masonry, etc. On the banks of the Caboclo Channel, 2,260 meters will be channeled along a stretch of the Linha Vermelha highway going up to the Trezentos neighborhood on the border with municipality São João de Meriti.

Residents fear that what is happening in Favela do Lixão is gentrification, a term that designates the process of segregation experienced in urban areas, characterized by the marked real estate appreciation of a given area culminating in the expulsion of existing residents due to increased cost of living in the area. This usually occurs when investors, developers, and wealthier residents begin to take an interest in areas previously neglected by the government and occupied by working class people.

As these investments increase, there are improvements in infrastructure, services, and commerce; the area is considered more attractive and, thus, real estate and rent prices increase. The idea is sold as a revitalization of degraded areas, bringing improvements in infrastructure, basic sanitation, security, and access to public services, in addition to valuing local real estate. However, this transformation leads to the displacement of low-income populations living in these areas—exactly those people who ought to be the beneficiaries of any local investment. Often, these communities are forced to move to regions further away, with less infrastructure, resulting in loss of social bonds, amplified inequality and greater difficulty accessing basic services.

An example of this phenomenon occurred in Rio de Janeiro’s Port Region where a vast revitalization process changed the face of the region under the justification of hosting the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Porto Maravilha (Marvelous Port), as the project was named, is the largest public-private partnership in the history of Brazil, costing over R$8 billion (US$ 1.6 billion). The public interest project came under pressure from the real estate market and various promises for social interest never materialized.

If nothing is done, there is a great risk of this being the fate of Favela do Lixão. Duque de Caxias city government must listen to residents and their demands for the community, without threats or impositions. City Hall will have to make a choice between two different city projects: one that guarantees residents much promised dignity and infrastructure, and another that whitens the region, making it an area for local elites through demographic changes.

About the author: Fabio Leon is a journalist, human rights activist, and media advisor with Fórum Grita Baixada.