Clique aqui para Português

In the neighborhood of Taquara, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, nestled in a place popularly known as Boiuna, on the edge of a local river, a small community lives out their days in the bustling metropolis. Crossing the discreet gate that guards the entrance, you will find long two-story buildings with apartments side-by-side and an extensive balcony on the second floor. There is a courtyard in front adorned with garden beds and trees, a church, and a community center. The name of the place sets the tone for the peace and protection that prevail: Shangri-lá. However, behind the buildings, in the collective memory of the residents who call it home, lies a long history of struggle and power.

Shangri-lá is a housing cooperative, the first of its kind in Rio de Janeiro. The community was built from the ground up by a significant portion of its residents through self-management and collective action. Its roots trace back to 1996, and since then, Shangri-lá has been home to families united by a shared vision of community living. They have taken on the responsibility of building and governing their territory. The history of Shangri-lá holds powerful lessons about the strength of collective struggle in securing the right to adequate housing in Rio de Janeiro—a basic need denied to millions of carioca families.

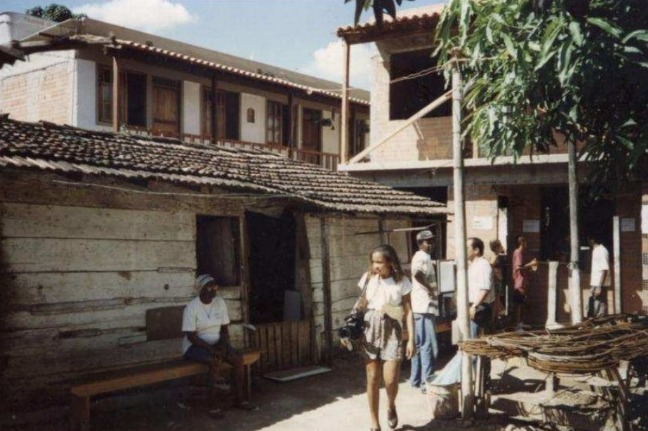

Before the creation of the cooperative and the construction of the houses, the community was part of a favela called Jardim Shangri-lá that emerged in the 1970s after the subdivision of a property in Taquara. The area saw informal occupations and house sales, but most families lived in makeshift shacks, often rented. In a section of the favela, 16 families lived in extreme precariousness—wooden houses prone to constant leaks. The surroundings lacked basic services like sanitation, electricity, and transportation. Despite these challenges, the families dedicated a significant portion of their income to rent, as told by Maria do Nascimento, a resident of Shangri-lá, better known as Dona Maria.

“The rotten shacks were falling apart. [People used to] go to the church to get wooden boards to line their shacks. Sometimes, they even had to get plastic to cover their roofs so they could sleep when it was raining.” — Maria Nascimento

Jurema Constâncio, a resident of Shangri-lá and regional coordinator of the National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP), shares that the owners of the old rented shacks showed little concern for the residents’ challenging situation. Their sole focus was collecting rent from families who, in turn, found themselves unable to improve their living conditions.

“There was someone who owned the shacks and collected rent. This person only showed up in the community when it was sunny. If it rained for a year, they wouldn’t show up at all. Because when they did, everyone would get on their case, demanding repairs—to change the roof, put in a floor, replace wood. But they wouldn’t allow it, so they wouldn’t miss out on the rent.” — Jurema Constâncio

The violation of the right to adequate housing was felt daily by residents of the Jardim Shangri-lá favela. It was in this context that a group from the Basic Ecclesial Communities (BEC), an inclusionary movement of the Brazilian Catholic Church focused on social transformation, began operating in the area. Father Josino held meetings during the community’s leisure activities, intertwining readings of the Bible with residents’ life challenges and discussing the collective construction of paths to improve conditions in the area. At this point, the National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP), a social movement advocating for the guarantee of the right to housing, self-management, and popular participation, also made its presence felt.

Thus, residents, organized through the social movement, along with BEC allies, began brainstorming possibilities to solve their housing crisis. These included improving the infrastructure of homes, access to a wider range of essential services, and ending rents.

The first step was to acquire the land, and for that, it was necessary to dialogue with the person who claimed to own it. As they soon discovered, the person collecting rent had tenure, as the real owner was never uncovered. This allowed them to negotiate the acquisition of the land at a more affordable price. Through donations and personal contributions, the residents collectively managed to obtain ownership of the land they had been paying rent to live on for years.

After overcoming the initial hurdle of acquiring the land, residents began contemplating housing models aligned with the community’s principles and objectives. At this point, the Bento Rubião Foundation Center for the Defense of Human Rights (FCDDBR) played a crucial role, providing technical expertise and connecting the residents’ struggles with other actors. The Foundation then organized meetings between Shangri-lá residents and other collectives and cooperatives experienced in housing self-management. They engaged in dialogues with projects in São Paulo and the Uruguayan Federation of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives (FUCVAM)—a pioneering organization in the cooperative movement in Latin America, pivotal in spreading cooperative housing experiences across the region.

Since then, cooperative principles have been integral to the development of Shangri-lá. These principles led residents to self-title their organization as a cooperative and draft a corresponding statute. Constâncio highlights the significance of the exchange with representatives from the cooperative movement in Uruguay.

“So, we got to know this experience and brought it to Brazil, here to Rio de Janeiro. Then, we got to work, spent a year working with the rules established by the bylaws they had in Uruguay so we could start adapting.” — Jurema Constâncio

Unlike Brazil, in Uruguay housing cooperatives are prevalent in cities, serving as a widespread means to access housing, with enabling legislation, making it easier to obtain financing and support. In Brazil, the cooperative logic was mainly introduced by the National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP), which began using the term “housing and mixed cooperative” in some experiences. Thus, the Shangri-lá Housing and Mixed Cooperative was born.

The struggle for adequate housing, however, was just beginning for the residents of Shangri-lá. The next step was to secure financing to build the houses. The funds came primarily from Misereor, a German organization affiliated with the Catholic Church, which financed part of the purchase of construction materials. In addition, individual donations and resources from the Bento Rubião Foundation itself, through a project called Ação da Cidadania (Citizenship Action), also played a role. This was still insufficient to cover the entire construction of the houses, leading the residents to explore alternatives and actively engage in the process. At that moment, the concern was not only about having the built houses as a final result but also empowering residents and ensuring a means of income generation for families. Therefore, they decided to set up a concrete block factory and autonomously produce the materials needed for the houses.

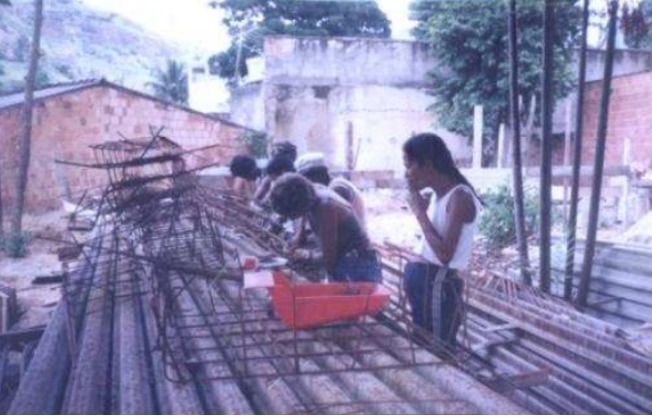

Another way to cut costs was to involve families directly in the construction of houses through mutual aid collective action events. This meant a significant amount of work, especially for families where everyone had to work to survive. The cooperative required 17 hours of collective work per week per family. Weekends were dedicated practically entirely to construction.

“Everyone worked as part of the collective action. People laid all the brickwork, doing everything right, you know? More cement, bricks. It was all up to us… We were the ones doing the work.” — Maria Nascimento

Despite the arduous efforts invested in the construction phase, those who participated in the collective action emphasize the importance of collectivity. According to the residents, it ended up strengthening bonds of support and solidarity among the cooperative members. Besides creating a feeling of community, a sense of belonging to the place: “It was a wonderful thing, a union,” recalls Dona Maria.

Throughout the collective action process, women played a central role. Female protagonism was evident from the conception of the housing project to the physical work of raising walls and building houses. Constâncio coordinated a significant portion of the project.

“When you have a woman at the helm, women feel calmer. But when it’s a man, who thinks you’re incompetent, who thinks you can’t do it, that your place is in front of a stove… So, we showed them it’s quite the opposite.” — Jurema Constâncio

After much struggle and collective organization, the residents finished building their homes. From a vulnerable situation, in extreme precariousness, living in wooden shacks without access to basic living conditions, they transitioned to homes capable of sheltering an entire family with dignity. These houses include a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, private bathroom, laundry area, and a porch—no longer needing to compromise their income on rent.

The sense of unity and collectivity developed by the residents was the result of the collective struggle for a basic human need: a place to call home. Without coming together to pursue this common goal, they probably would never have achieved the dream of dignified housing. Community organizing, through cooperation and self-management in every phase of the process, contributed to the flourishing of a strong support network and trust among residents. Each one carries a part of this story in their memory.

Today, the Shangri-lá Housing and Mixed Cooperative is home to 29 families. Even with the houses ready and people living in good conditions, challenges persist. The land situation in the community has not been fully regularized, leaving residents in a state of uncertainty regarding security of tenure. The growing presence of vigilante off-duty police militias also poses new threats to the well-being of the area. Additionally, longtime residents report a weakening of unity and the sense of collectivity after the houses were finalized. To some it was as if, after all the collective struggle, each person entered their own home and started to lead their own individual life.

The new challenges in Shangri-lá led to the search for new solutions. Currently, residents are exploring ways to preserve the collective spirit in the management of their territory and land regularization. Self-management, a principle that has always been present in the cooperative’s history, continues to guide local leadership, seeking an organizational arrangement that ensures participatory decision-making. Another demand is for land regularization, a way to ensure that all efforts to secure housing are not lost. They seek the official recognition of Shangri-lá’s right to land. However, some fear that individual titles could further harm the local sense of collectivity and exacerbate individualism, while simultaneously attracting the risk of real estate speculation which would lead to higher rents. One possibility being discussed is the Community Land Trust (CLT) model, a new land management model in Brazil introduced in the draft bill of Rio de Janeiro’s Master Plan. Since 2022, there has been an ongoing project in Shangri-lá to discuss the CLT as a potential land solution for the community, maintaining the ideal of collective land management strongly advocated by its cooperative principles and, at the same time, ensuring individual autonomy in the use of housing.

The history of the Shangri-lá Cooperative provides important lessons for examining housing issues and their challenges. The challenge of access to housing is often approached in a dual manner: either with the State as the protagonist or as something to be left to the market. Shangri-lá, however, offers a third path: housing achieved through the action of residents themselves, the social production of habitat. The legacy of this approach can be seen in the walls, doors, and windows of Shangri-lá, all of which hold a history of community protagonism. A process that was responsible for building much more than houses but, rather, an entire community.