Clique aqui para Português

In November 2023, Ashley Allen, executive director of the Houston Community Land Trust, visited Rio de Janeiro for the Favela CLT Project‘s* 5th Anniversary and 3rd National Seminar. The event focused on collective ownership of land and community spaces as offering resistance to real estate speculation and gentrification, while residents maintain ownership of their homes, ensuring security of tenure. In celebration of World CLT Day 2024, we are thrilled to share this insightful, deep-dive interview with Ashley.

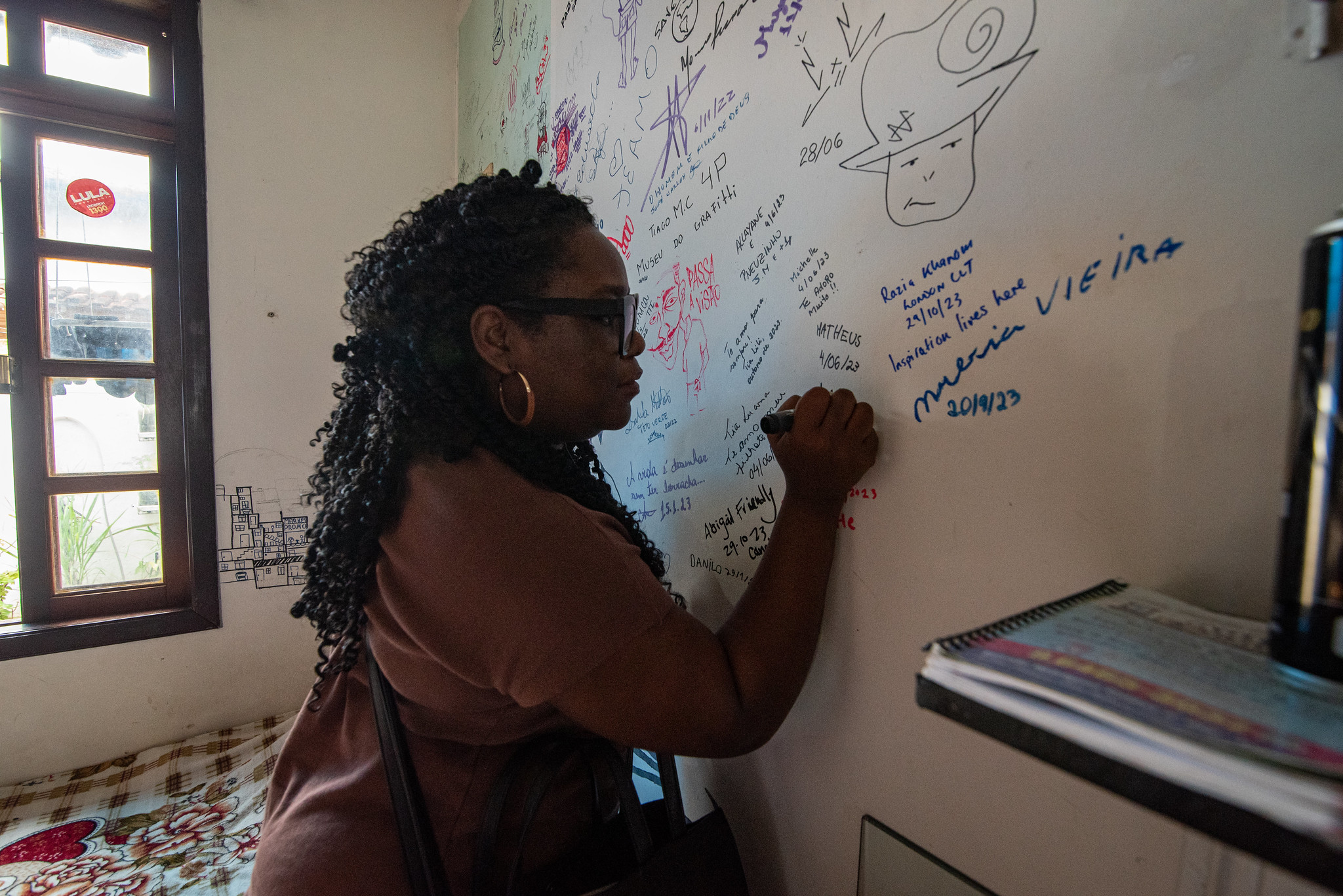

At the event, Allen spoke about her experiences advocating for affordable housing as a Black CLT leader in the United States. Though the seminar lasted only one day, the bonds Allen built with organizers from Brazil and elsewhere stretched much further. These relationships exemplify how livable, sustainable communities across the world are rooted in personal ties.

We sat down to speak at the end of the event, after the audience and members of the Favela-CLT Project sang and cut a blue-and-white birthday cake. Despite her busy day, Allen spoke to RioOnWatch at length. She talked about the origins of CLTs in the 1960s Civil Rights and Black Power movements, and how the US and Brazil face connected challenges stemming from their entwined histories of slavery and oppression.

RioOnWatch: How would you explain a Community Land Trust (CLT) to someone who’s unfamiliar with the concept?

Allen: I would say that a CLT is an organization where the community has control over the land to create long-term affordability, to make sure that whoever is within a space is able to stay there as the market changes.

RioOnWatch: What does it mean to be an effective steward of land and housing for your community?

Allen: Listen to the community, that’s number one. If the community says, “We can’t afford it,” then we need to make it work. If they’re saying, “We’re being displaced,” we need to look there. If they’re saying, “It’s vacant and it’s not attractive to the community,” then you put something on it. That’s the thing: doing what the community has asked you to do. And doing what you promise to the community.

We have people who go and say, “We are going to build affordable housing.” And we’re like, “Affordable for who? You’re using that term but you’re not really making affordable housing.” And so, again, doing what you said you were going to do, and really doing it. Not coming in under one premise and then developing something else or doing something else. That’s really it. Communities want something, you do it.

RioOnWatch: How did you become a community organizer?

Allen: I became a community organizer unexpectedly. I was a homeless youth [in North Carolina], and my family was homeless on and off for about ten years. When I moved to Chicago, I felt like I hadn’t really expressed how I felt about that long period of housing instability. What does that do for a child and my development? I hid it for so long from so many people, from friends and family that didn’t even know, and so I just wanted a way to get it out and get a source of healing.

So, I thought about doing it as a volunteer. I went to a couple of events and heard other people tell their stories about their experiences of homelessness, and then I joined the Speakers’ Bureau [at Chicago’s Coalition for the Homeless]. I went around the city of Chicago, to different organizations and schools, to talk about my experience.

After that, they asked me to join a campaign. They trained me as a community organizer in Chicago, which is the birthplace of community organizing. That’s how it started. I was hooked after that. I loved coming up with solutions, not just talking about what’s wrong but thinking about ways to encourage change. They crafted me into being the community organizer that I am today.

RioOnWatch: What was it like learning how to be an organizer in a city with such a strong activist legacy?

Allen: It feels like you’re standing on the shoulders of something so big. It’s a heavy lift. But I think because it has such a great history of organizing, they do such a great job of teaching the history, teaching the strategies, getting in there and seeing it for real, and doing the work very soon after. It’s teaching by doing.

Actually, I ended up doing more on the education side, changing education and policy debates so that educational barriers are not there. It wasn’t just about organizing. I learned about policy and so many other issues.

RioOnWatch: Did your work in education help prepare you to speak to different groups of people?

Allen: Oh, absolutely. Education is another issue that impacts everybody. And being able to think: “How does it affect you individually? How does it affect this business?” Being able to pinpoint those things works across all issues: housing, education, healthcare. Being able to meet people where they are. How does the individual improvement of my housing situation, my education situation, healthcare, really help the greater good? Business groups, big corporations have vested interests in this too.

RioOnWatch: What are some unexpected relationships that you have built? How do you build trust among diverse communities?

Allen: I came into Houston not a Houstonian, so people were already a little leery. But I was brought in because I was an outsider, not someone who’s already connected, or already entangled with the problems taking place and the expectations.

I was coming in not knowing anyone, and I was able to build relationships from a very solid foundation from the very beginning. So, it was first making the community understand that the Community Land Trust was an option, it was a tool.

It wasn’t about just coming in, like, “You buy a house in a Community Land Trust.” It was really about us informing people about what’s going on in their communities. It started off, the relationship being, “Okay, what’s going on in your community?” “Yes, we see it, this is true. Yes, a lot of these homes are not affordable,” but here’s a way we can try to fix that. Yes, you’re being displaced. They are probably going to come for your homes and your land and you’ll probably be pushed out.”

I moved in the middle of the pandemic. Building relationships was difficult, because I was isolated for awhile. But the relationships that we built across sectors were really important to what we were trying to do. It wasn’t just homeowners in the community or people trying to stay in their homes, but everyone involved in the taking of land, and who was helping us preserve it.

RioOnWatch: What are some communities that are important to you?

Allen: Single moms, because I was raised by a single mom. That responsibility of providing a home for your children is really important. That was something my mom struggled with. Right now in Houston, the 3rd and 5th wards are important to me, because those are communities that I can identify with. They’re historically Black communities with close-knit, vibrant populations that are very important to the fabric of Houston.

They’re being wiped out very quickly. We haven’t been able to jump in there fast enough to really make an impact. Right now, with the money we have, we’re going to be pulling a lot for those particular communities before they’re not recognizable.

RioOnWatch: How do CLTs build on Black history, neighborhoods, communities?

Allen: 79% of our homeowners are Black. You have people who are not Black or Hispanic as homeowners. But we target those who have the hardest time getting approved for mortgages, communities that are mostly scheduled for gentrification and displacement. Unfortunately, these are mainly Black communities.

We make sure to do our outreach in those places, getting them to understand why this is so beneficial to them. It’s not just them getting a home, but feeling supported in their communities as a whole.

Going to churches is one way Black people get a lot of their information, and they trust the church. We did partner with a lot of pastors to get them to understand why Community Land Trusts would be beneficial to building their congregation. What they [pastors] brought up to me is that this is in their best interest, because if their congregation moves away, who’s going to support the church?

RioOnWatch: Can the ethical system of CLTs align with religious teachings?

Allen: Absolutely. We’re talking about looking out for your fellow man, making sure not just that you’re good, but your family, your neighbors [are good]. Thinking about your neighbors, and thinking about not “me” as a human, but “we.”

That is something culturally that I think most of us are brought up to believe. Religion is about giving back, and making sure everyone’s okay. No matter what your sect is, or your religion or your faith, it all comes down to being a good person. How can you be a good person when you’re not thinking about everyone in the community, only you? Now, I believe in making sure you are okay as an individual, and making sure that your family is good, but there is also a greater good.

RioOnWatch: Do you see your work as building on the Civil Rights movement?

Allen: Yeah, and that’s it. This work is based on the Civil Rights movement. It’s based on collective organization, collective work through collective fighting, to observe and hold on to culture and legacy.

It’s unfortunate that we still need to have civil rights action today, but the reality is that the country I live in, the United States, and here in Brazil, are rooted in the oppression of people. The policies and systems are built on how best to do that [maintain oppression].

I see the CLT as a continuous way to be a system changer. It’s not just a program, it’s not just a two-person issue. We’re changing the way land, and the way housing, is accessed and distributed. Because, ultimately, if we look back on it, it was about the individual white man. You had to be a slave owner to own land. These are the people who had ownership of the United States and other countries.

You have to change the system so that the ownership is not concentrated in the hands of an individual white man, but of a group of people who actually care about it for the future generations.

RioOnWatch: What are some similarities you find between Houston and Rio, or the US and Brazil more broadly?

Allen: I was very shocked by some of the things that I learned about Rio. It’s sadly all rooted in the fact that the United States and Brazil, we’re both countries that have had roots in the slave trade. Our systems are very similar. Some of the barriers are very similar, when it comes to it being harder for Black people to be uplifted. It’s not impossible, but it’s not easy. The way that Black people are treated by police here, it’s very similar to what is happening in the United States. It’s similar to how there’s little respect for Black communities by law enforcement.

It’s a little disappointing, but also it helps, because then you build that connection and say, “Okay, how can we solve this?” You’re getting ideas from other places around the world that understand these challenges and are having these conversations and bring in new ideas that you may not even know about.

I love the sense of community. I see how communities come together, and there’s love around food, and there’s love around music, and there’s love around all these cultural things that make you feel good, and give you that sense of community, and I see that. In particular, me coming from small towns where everybody knows everybody, or if you’re from a big city, a particular neighborhood, and everyone knows everybody, seeing those similarities and some of those tight-knit communities, similarities in what they’re centered around.

RioOnWatch: In your day-to-day work, how do you deal with bureaucracy and other challenges?

Allen: With housing, one of our biggest barriers is that developers are always going to win over the people who are actually trying to address the issue of housing. Even with a permit. Who can pay to have it expedited? Who can afford it? Big money developers can. Affordable housing developers cannot.

It’s frustrating. And it’s hard. What you have to do is, you have to show results. That’s number one. What’s been easy for us is that our housing department in the city has not been very productive at all. For us to outshine them has not been that hard because the bar is very, very low.

Because we’re city funded, people are a little bit more skeptical, and so we always have to make sure we’re on top of everything that’s done. It’s more work, but I think when you’re funded by a highly scrutinized system like city government, we have to just be a little bit more diligent in how we operate. That’s how we do it, just making sure we are really doing things above board at a high level of excellence. Unfortunately, municipalities are not known for being the most efficient. So, you just wait for them to expose themselves.

I was losing sleep, I was so angry. I was so frustrated with their behavior. They took our money and gave it to developers and said the developers are going to lower the prices of the homes and make them affordable. I said, “No they’re not, because developers are never going to cut into their profit. They’re just going to make more profit. You gave them more money, they’re just going to make more profit.”

And that’s exactly what happened. We told them that. They didn’t want to hear it. Here we are, a couple months later, front page of the Houston Chronicle. They lost US$ 60 million. It’s like we did all that fighting, all we needed to do was wait.

My board member said that. She was like, “Ashley, why are you upset about something that you already know to be true? Why are you upset with how they operate? They’re not doing anything that you’re surprised by. You work around it. Because you know what they’re doing. Because they don’t change their ways. You work around it.” Unfortunately, that’s it.

RioOnWatch: What kind of potential is there for international solidarity and collaboration?

Allen: When I go back and speak to my city council, I’m going to mention this trip. Like, “Hey, people know what we’re doing in Houston, this is worldwide. And also we’re not doing something that they’re doing in Rio.”

If we’re being recognized internationally, and bringing international ideas in, that’s a good look for the city. So, I think we can all benefit from idea exchange, from being in the conversation, and saying, “Hey, our city is being represented globally.”

RioOnWatch: What does the global scale of things say about the future of urban housing and planning?

Allen: I do hope that we start to look at long-term solutions globally. What really frustrates me in a city like Houston—that is prone to natural disasters, a large city, the fourth largest city in the United States—is that we have the tools, we have the money, we have the land. There’s no reason we can’t solve this issue.

My hope is that mindsets change and people open their minds. So that people actually address the problem and everyone else will follow in line. That across the board, across the world, people will start to open up their minds and say, what we’ve been doing isn’t working. There are too many people that are housing insecure, there are too many people that are homeless. Why are we not pushing the issue of housing? It is a basic human right. There should be a global summit for housing. Why are we not doing that?

We can do a global summit for the new iPhone. They bring everyone together, they talk about the new features that aren’t even that new, and we can’t bring people together to talk about housing, which is a worldwide issue. It doesn’t make sense. We do need to start changing how we do housing and not just locally. Let’s have that conversation worldwide.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

*The Favela CLT Project and RioOnWatch are both initiatives managed by Catalytic Communities (CatComm)