Clique aqui para Português

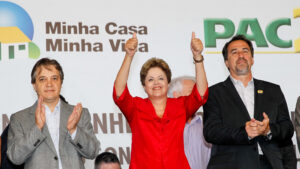

Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV; in English “My House My Life”) is Brazil’s first-ever effort at large-scale public housing, an ambitious nationwide program tasked with constructing 3.4 million homes as part of a broader effort to upgrade and modernize the nation’s cities.

Participants of the program are offered financing options to either buy a home constructed by the government or to renovate an existing one. Families with monthly incomes of less than R$5,000 are invited to apply, with priority given to families who earn less than R$1,600 per month.

MCMV is funded primarily through the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), a federal infrastructure-upgrading program. Contracts for construction of the properties are awarded by Caixa, the government-owned bank responsible for managing a number of federal programs. Caixa is also responsible for facilitating the participant selection process in conjunction with municipal housing authorities and for overseeing financial transactions between the government and participants.

MCMV is funded primarily through the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), a federal infrastructure-upgrading program. Contracts for construction of the properties are awarded by Caixa, the government-owned bank responsible for managing a number of federal programs. Caixa is also responsible for facilitating the participant selection process in conjunction with municipal housing authorities and for overseeing financial transactions between the government and participants.

MCMV was first instituted in 2009 to provide improved housing for an estimated 7 million Brazilians residing in sub-optimal living conditions. The program received a budget of R$34 billion (USD $17.55 billion) to construct one million homes. Funding was divided between two sub-programs: the National Urban Housing Program and the National Rural Housing Program. MCMV is most closely associated with the National Urban Housing Program, which promotes urban redevelopment and provides new homes for low-income families. The National Rural Housing Program on the other hand, provides loans for farmers and rural workers who earn less than R$60,000 annually (USD $26,900) to make improvements to their homes.

After successfully contracting the first million units, the second phase of MCMV was established in 2011. The second stage has an allocated budget of R$72 billion (USD $35.1 billion) and promises to build an additional two million homes by 2016. Minister of Cities Gilberto Occhi announced that as of April 2014 approximately 2,400,000 housing units have been constructed, leaving at least 400,000 units to be completed in this phase of the program. Occhi also indicated that government officials are currently preparing the launch of a third stage of MCMV but have not yet established goals or procured funding. An official announcement of the third stage is expected in June with a tentative rollout scheduled for early 2015.

Minha Casa Minha Vida in Rio

In Rio, construction of MCMV units has been particularly hasty as the city prepares to host two successive mega sporting events. At least 66,270 housing units have been contracted to date (already turned in or under construction), with a projected goal of having 100,000 units completed by 2016. Of the completed homes, 33,363 units have been reserved for families with monthly incomes of less than R$1,600 (USD $720) and 11,612 units have been reserved for families whose monthly incomes are between R$1,600 and R$3,275 (USD $1,475). Individuals and corporations have contracted the remaining 16,450 units.

Over half of MCMV properties in Rio are located in the West Zone, a huge, largely underserviced region. These housing developments have been widely criticized by residents for lacking adequate infrastructure and transport links, and reside in militia-controlled territories in neighborhoods such as Santa Cruz, Cosmos and Campo Grande. Families accustomed to the intricate social networks and mixed-use properties in Rio’s favelas have had trouble adjusting to the single-use and highly regulated MCMV complexes that offer little in the way of public or commercial space. Residents who work in the South Zone or North Zone must now accommodate significantly longer commutes, making continued employment in the city’s commercial center difficult. Several MCMV properties have also been criticized for poor construction quality, the worst incident requiring demolition following the appearance of huge cracks in the R$19 million investment, and another notable case resulted in the evacuation of families from Bairro Carioca last year after apartments on the first floor were flooded.

Urban planners and government officials have also been critical of the MCMV properties being built in the West Zone. Antônio Veríssimo, the Director of Coordination and Planning for the Municipal Housing Secretariat published an article in 2010 in which he argued such dense concentration of public housing in the region would create “further ghettos of poverty.” Mayor Eduardo Paes has since prohibited further construction of MCMV units in the West Zone, electing instead to relocate contracts to the city’s North Zone.

Urban planners and government officials have also been critical of the MCMV properties being built in the West Zone. Antônio Veríssimo, the Director of Coordination and Planning for the Municipal Housing Secretariat published an article in 2010 in which he argued such dense concentration of public housing in the region would create “further ghettos of poverty.” Mayor Eduardo Paes has since prohibited further construction of MCMV units in the West Zone, electing instead to relocate contracts to the city’s North Zone.

Additionally controversial is the fact that over half of the city’s new public housing stock will be occupied by families forcibly removed from their homes for projects related to the city’s mega-event development projects. Communities such as Vila Autódromo are experiencing demolitions and ongoing eviction pressure, with families offered a choice between a monetary payout and MCMV apartment as compensation. In some cases, evicted families lived in homes of far higher quality and larger than the apartments offered, but are nevertheless given MCMV units. As a result, qualifying families who are in dire need of housing and have elected to participate in the program are placed on a waiting list for available apartments.

Despite the various controversies of MCMV, some residents have leveraged government investment to create innovative housing projects. Housing cooperatives such as Quilombo da Gamboa in the Port Region and Grupo Esperança in Colônia Juliano Moreira are financed by a Minha Casa Minha Vida offshoot program called Entidades (MCMV-En) and offer a radically different vision for public housing in Rio. While the majority of MCMV apartments are designed and constructed by third parties, these housing units are designed with input from co-op members and with the specific intention of encouraging community development through integrated public space. Such collaborations offer a positive and effective method for improving living conditions of favela residents, but only account for only 5-10% of the MCMV budget.