‘Please be careful when you open the overhead luggage after landing, and please remember there is still time to give a donation to our youth program in the favelas. Your donation can help a young person get out of a life of misery, drugs and poverty.’ Misery. Drugs. Poverty. The pilot that landed my plane at Galeão International airport had in three words summarized the most commonly heard dogmas about the favela.

The word favela is commonly associated with the word slum, shantytown, squatter community or ghetto. Each of these words carries a negative connotation, slum implies squalor, shantytown suggests precarious housing, squatter community hints at illegality and ghetto presupposes violence. None of these definitions do justice to the richness of favela culture or acknowledge the historical place of the favela in Brazilian history.

In this article I will give a short overview of where the term favela comes from and how and where the stereotypes about the favela originated. The term favela is first found in 19th century Portuguese dictionaries, referring to the favela tree commonly found in Bahia.

After the ‘Guerra de Canudos’ (Canudos War) in Bahia (1895-1896) government soldiers, who had lived amongst the favela trees, marched to Rio de Janeiro to await their payment. They settled on what is one of Rio’s hills and renamed the hill ‘Morro da Favela’ after the shrubby tree that thrived at the location of their victory against the rebels of Canudos. The government never paid and the soldiers never left and so the first favela came to be. But if the favela was occupied by victorious soldiers, how did it come to have the negative connotation it has today? The development of the (stereotypical) representation of the favela in popular and academic writing can be divided into four distinct periods starting in the early 1900s.

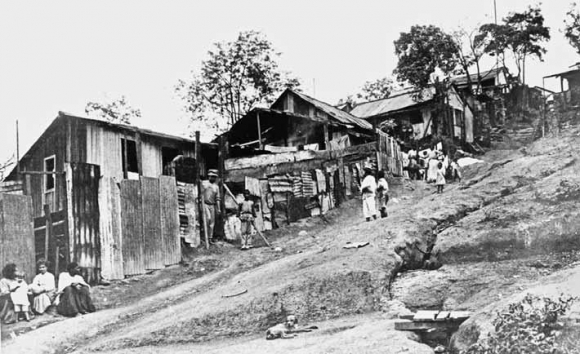

The first, which ranges from the early 1900s until the 1940s, precedes the development of social sciences in Brazil. Many descriptions of the favela at the time came in the form of journalistic or historical writing. The most well-known example stems from Euclides da Cunha’s famous book ‘Os Sertões,’ which covers the Canudos War. Da Cunha’s description of the ‘the coast versus the backlands’ as the opposition between cultured and uncultured, is applied to explain the difference between ‘a favela e a cidade’ (the favela and the city).

This image of the favela was confirmed by architects, social workers, and doctors that entered the communities in the early 1900s. In their essays the favela was described as backwards, unsanitary and oversexualized. This period was highly significant because it created the image of the favela that would continue to predominate popular representations throughout the 20th and 21th century.

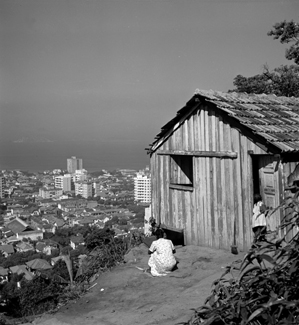

The second period ranges from the 1940s until the mid 1960s. In the early ’40s favelas were seen mainly as a social problem hindering urban planning of the ‘Marvellous City.’ In 1950 the IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Statistics) carried out the first census in favela communities. The IBGE census showed that in 1950 there were 58 favelas, with 169.305 inhabitants. When the official statistics showed that only roughly 7% of the total population of Rio de Janeiro at the time lived in the favelas and that the majority were ‘trabalhadores,’ or workers, this somewhat tempered the negative image of the favela.

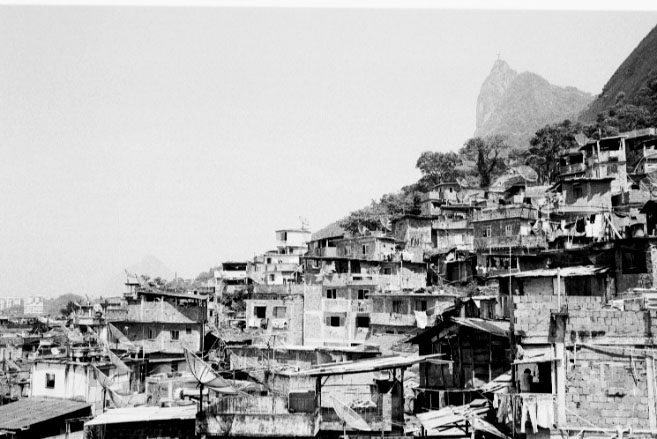

The third period, beginning around 1965 shows an exponential increase in the number of publications on favelas. This period can be described as the moment in which the favela becomes a certified academic research subject. They had been growing in size since the 1940s housing crisis and the increased migration from the Brazilian interior to Rio de Janeiro further expanded the communities. The exponential growth of favela communities also increased their visibility.

As Brazil’s civil society expanded, growing attention for the favela led to NGOs increasingly entering these communities, setting up programs and doing their own research, adding to the growing body of literature. This was a particularly important period for the favela because the increase of case studies led to a more nuanced picture of these neighborhoods, ridding them, in academic circles, of their negative image. And it is with this more context-sensitive picture that we are entering the fourth period of writing on the favela that started roughly around 2010.

Yet in everyday conversation, be it on the corner at the juice joint or when landing at Galeão Airport people still refer to the favela in negative terms. In O Globo‘s Sunday economic editorial the favela is described as finally having a chance at succeeding as a community ‘now that the state has entered and the gangs have left’ (O Globo Economic editorial 12/02/12).

Neither the word on the street corners nor the journalists working for O Globo are helping change the dogmas commonly held about the favela.

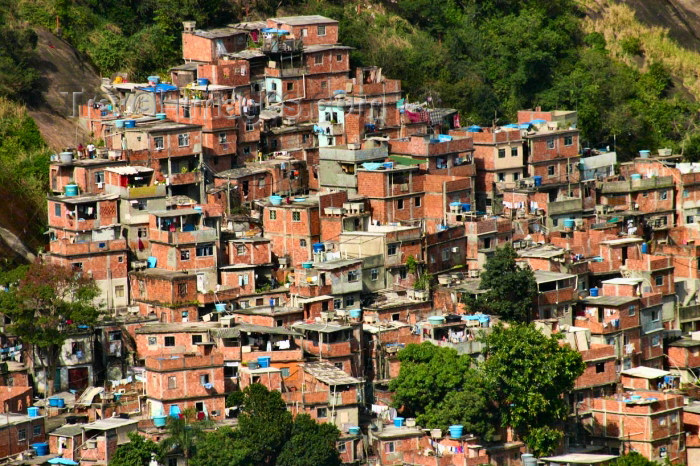

In order to truly change its image, a first step would be to refer to its true-form. The favela should not be seen in terms of Misery, Drugs and Crime. But by definitions that represent their nature as horizontally structured solidary communities, which hard-working people have spent decades investing in and building neighborhoods with scarcely a government service.

Favelas are not ‘hubs of poverty,’ the people who live inside these communities are not ignorant or complacent. Quite the contrary, they possess a ‘do-it-yourself’-spirit and a ‘build-your-own’ mentality that Brazilian mainstream society has much to learn from.

Sources used and recommended:

Arias, Desmond E.

2006 Drugs and Democracy in Rio de Janeiro: Trafficking, Social Networks and public Security. Chapel Hill: North Carolina University Press.

Goldstein, Donna M.

2003 Laughter out of place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shanty Town. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Perlman, Janice

1976 The Myth of Marginality, Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro. Berkeley: University of California Press.

2010 Favela: Four decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pino, Julio C.

1997 Family and Favela: the Reproduction of Poverty in Rio de Janeiro.

Westport: Greenwood.

Portes, Alejandro

1979 Housing Policy, Urban Poverty, and the State: The Favelas of Rio de Janeiro, 1972-1976, Latin American Research Review, 14(2):3-24.

Valladares, Licia

2006 La favela d’un siècle à l’autre. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

2009 Social sciences representations of favelas in Rio de Janeiro: A Historical perspective, LLILAS Visiting Resource Professor Papers, 1- 31.