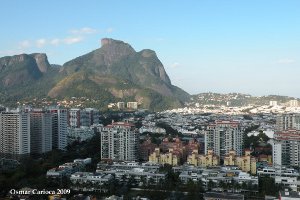

Zoom out from Copenhagen, away from Copacabana, and let’s take a stroll a few kilometers west of Copacabana, inside the city of Rio, in Barra da Tijuca, an area of the city once characterized by endless marshes, that has been entirely developed over the past 30 years. Rio’s “Miami,” as many refer to it, Barra da Tijuca is characterized by 5- to 15-story buildings, just blocks from the beach with no mixed use. Moving away from the beach, and the private condos, one finds private shopping malls lining the main thoroughfares. Residents drive between apartment blocks, each featuring its own private gym, swimming pool, and often bakery and other facilities. They then drive to the malls. Any planner leaving Copacabana and heading towards Barra can see that (a) planners had little to say when Barra was developed (the area was developed overwhelmingly by private real estate developers), and (b) it was developed in a way as to guarantee minimal contact with the city’s poor, with no concern paid to transit efficiency, a sense of community, or even the effects of raw sewerage. In short, Barra was developed with little forethought. What will sell now to people who think only about today? Rio’s community organizers complain about the individualism and lack of ethics inherent in local culture. Barra was built in response to this and the city’s well known class division. And, to the proponents of Barra-style development, the seemingly ever expanding wave of luxury condos spreading across the city’s western horizon, without a favela in sight, has been a source of satisfaction.

This brand of development is the golden vision of Rio’s dynamic and youthful new Mayor (as of January 2009), Eduardo Paes, who himself was raised in Barra. Paes is the first of Rio’s mayors to benefit from a combination of a capable technical team, a time of economic prosperity, and good relations with the governor and president. Hence, powerful circumstances to see his will through.

Yet on the far edge of Barra, next to Jacarepaguá Lagoon, and across the street from 5 new luxury condos, there’s an apparent “stain” on the horizon. Vila Autódromo, settled over 40 years ago by fishermen who lived subsistence lives kilometers away from the developed part of the city, and later by workers brought to the site to build the city’s racetrack, is today a working class neighborhood with some 4000 residents.

When the first fishermen arrived here decades ago, the lagoon was immaculate. Today, it receives sewerage and garbage from neighboring apartment blocks. The fishermen who remain complain of times when there are no fish. Only the occasional Tilapia, a fish that feasts on detritus. Yet residents recount 1992, when the city tried to remove them for the first time, alleging that Vila Autódromo posed “aesthetic and environmental damage” to the surrounding area in a judicial action requesting the full removal of the community. This came at a time when Barra had shown itself the new destination for commercial, sports, and residential facilities, which, as was made clear by the judicial action, meant that a “new aesthetic” – one where the poor were excluded – was necessary.

Community organizers worked effectively on two fronts, through judicial channels and with the State government, to secure their stay. They worked with the State of Rio’s government that owned the land to prove they had been settled there already for decades. As a result, in 1994 Vila Autódromo received title with the right to use the land for 40 years from Governor Leonel Brizola. They also worked with public defenders through judicial channels, blocking municipal attempts at eviction.

Despite having received title from the state, on several occasions, from the widening of a neighboring road to preparations for the Pan-American Games, municipal officials have threatened the community with removal, including Paes himself when working within previous administrations. The Olympics offered just the opportunity.

Days after the announcement that Rio had been chosen to host the 2016 Olympic Games, the city’s largest daily, O Globo, announced plans to remove Vila Autódromo to make way for Olympics venues.

In the aftermath of this article I visited Vila Autódromo and neighboring communities. Residents were visibly frightened. Community leaders complained of panic attacks. As one man spent yet another day building his home—a form of nonviolent resistance, if you will—he told me how he felt when the decision was made in Copenhagen: “I sincerely knew there would be complications for us. I’m Brazilian, I’d really like these Olympics to be held in Rio, but I was rooting for us not to win. Because we would run this risk.” Then he repeated, “I’m Brazilian, I wanted so much for the Olympics to be held here. But because I knew we’d once again face pressure (to leave), I was rooting that we wouldn’t be chosen.”

One can sense the internal conflict as he experiences it. On the one hand, this city, marked by stagnation and violence, despite such incredible potential, might turn around with investment from such an event. On the other, municipal officials can’t be trusted to make use of such an opportunity in a way that is fair and uplifting.

Characteristic of “business as usual,” it was only through Rio’s largest daily that residents learned of their fate. At no time in preparing the bid for the Olympics or announcing the plans did the City visit the community to learn of its unique characteristics or seek out local leaders to consider alternatives. Nor did residents receive the information “from the horse’s mouth,” leaving them uncertain as to the details of the decision, who would be affected, when, or whether it was true at all (as the press are not required to publish accurate statements).

“The 2016 Olympics: A Win For Rio?” is a five-part series by Theresa Williamson.

Check out part 1, part 3, part 4 and part 5.