Say what you want about Morar Carioca, the latest incarnation of Rio’s favela upgrading programs, but you can’t claim that it’s lacking in ambition – at least not on paper. The initiative, which is actually an expansion and reboot of previous programs, aims to spend approximately R$8 billion to urbanize Rio’s over 1000 informal settlements by 2020. According to the Municipal Housing Secretary’s (SMH) promotional materials, for each of its projects, Morar Carioca aims to provide infrastructure and public services and their maintenance, a healthy environment with more public space, limits on future growth, land regularization, and improved accessibility – all with a focus on social integration and environmental sustainability, and all in less than ten years. A tall order, to be sure, but what’s not to like?

Say what you want about Morar Carioca, the latest incarnation of Rio’s favela upgrading programs, but you can’t claim that it’s lacking in ambition – at least not on paper. The initiative, which is actually an expansion and reboot of previous programs, aims to spend approximately R$8 billion to urbanize Rio’s over 1000 informal settlements by 2020. According to the Municipal Housing Secretary’s (SMH) promotional materials, for each of its projects, Morar Carioca aims to provide infrastructure and public services and their maintenance, a healthy environment with more public space, limits on future growth, land regularization, and improved accessibility – all with a focus on social integration and environmental sustainability, and all in less than ten years. A tall order, to be sure, but what’s not to like?

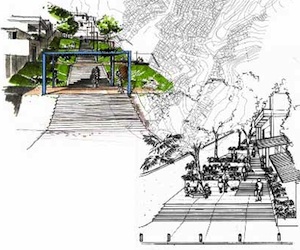

The key difference between Morar Carioca and previous programs is that, like so much in Rio these days, development for the Olympics is driving the process. While the Inter-American Development Bank stands as a major financial contributor, as in the past, resources for Olympics projects are being dedicated to Morar Carioca. This means that, once the SMH kicked off the process last year by taking an inventory of the city’s favelas and loteamentos, classifying them by their location, size, environment risk, and feasibility of upgrade, they expressly prioritized those communities for investment based on their proximity to the four Olympics development clusters. Then the SMH, in partnership with the Instituto de Arquitetos do Brasil (IAB), held a competition awarding forty design teams the opportunity to head up development for those highest priority communities. The design plans for these communities are impressive, but the communities they serve are not necessarily the ones most in need.

Prioritization aside, a more basic worry lies in the historic gulf between the image of ambitious plans and their substance, between the rhetoric and the reality. Community residents have seen this movie before.

Brazil, over more than a century, has staked out a brash position near the leading edge of international movements in architecture and urban design. And Rio in particular has been a showcase of splashy, but heavy-handed, urban interventions. A “Belle Époque Carioca” saw Rio’s colonial port city character transformed by the grandiose aspirations of Parisian boulevards and neoclassical monumentality, a process that razed nearly three thousand low-income dwellings. Later on, the master plan for the undeveloped West Zone at least gave lip service to decent affordable housing and an inclusive public life, but anyone who has visited the privately-territorialized, controlled-access expanse of Barra da Tijuca knows what came of those plans. In project after project, the promise of “urban renewal” turned into the nightmare of eviction and dispersal.

Brazil, over more than a century, has staked out a brash position near the leading edge of international movements in architecture and urban design. And Rio in particular has been a showcase of splashy, but heavy-handed, urban interventions. A “Belle Époque Carioca” saw Rio’s colonial port city character transformed by the grandiose aspirations of Parisian boulevards and neoclassical monumentality, a process that razed nearly three thousand low-income dwellings. Later on, the master plan for the undeveloped West Zone at least gave lip service to decent affordable housing and an inclusive public life, but anyone who has visited the privately-territorialized, controlled-access expanse of Barra da Tijuca knows what came of those plans. In project after project, the promise of “urban renewal” turned into the nightmare of eviction and dispersal.

In a step forward, the 80s and 90s saw a shift in official policy from slum eradication to upgrades and urbanization. A series of initiatives, foremost among them the Favela-Bairro programs, sought to stitch Rio’s informal communities back in the formally built urban fabric through a combination of infrastructure provision, public realm enhancements, land regularization, reforestation, and the insertion of human development amenities, such as health clinics and community centers. It was with Favela-Bairro, which happened over two phases, that the notion of “social integration” was brought to the fore. Favela-Bairro would not only improve living conditions in favelas, but it would heal the social divisions between the morro (hillsides, informal communities without services) and the asfalto (asphalt, or areas with services).

Was it successful? The program has improved living conditions for some, and is certainly preferable to the favela eradication programs of the past. But because Morar Carioca is essentially the third phase of Favela-Bairro, future efforts must be cognizant of past failures. Here are a few.

First, there needs to be a greater emphasis on social investment. While “slum upgrading” programs in general are meant to be holistic – with social and environmental improvements coexisting with physical ones – Rio’s long-standing ardor for design solutions has tended to overshadow the unsexy business of making job training, health and education accessible to all. Phase I of Favela-Bairro, despite championing the holistic approach, postponed and ultimately cancelled many of the human development components, which were incorporated to a greater, but still insufficient, degree in Phase II. Morar Carioca suffers from a similar emphasis on physical improvements.

First, there needs to be a greater emphasis on social investment. While “slum upgrading” programs in general are meant to be holistic – with social and environmental improvements coexisting with physical ones – Rio’s long-standing ardor for design solutions has tended to overshadow the unsexy business of making job training, health and education accessible to all. Phase I of Favela-Bairro, despite championing the holistic approach, postponed and ultimately cancelled many of the human development components, which were incorporated to a greater, but still insufficient, degree in Phase II. Morar Carioca suffers from a similar emphasis on physical improvements.

Second, the commitment to the community must be sustained in order to ensure that improvements do not degenerate. The open air museum at Morro da Providência and a number of other public space insertions are today lightly used due to a perception of danger. Child care and community centers had a splashy unveiling but many now lack adequate funding for staff and maintenance. Poor materials used for roads and sewerage systems in communities mean they enter disrepair often within less than 3 years.

Third, while Favela-Bairro made claims of involving local residents, in practice only in a few communities did participation and ownership over the projects effectively occur. While the official process provides for community input from the first stages of needs assessment forward, these procedures are rarely followed, and they generally result in bureaucrats making virtually all of the investment decisions.

Third, while Favela-Bairro made claims of involving local residents, in practice only in a few communities did participation and ownership over the projects effectively occur. While the official process provides for community input from the first stages of needs assessment forward, these procedures are rarely followed, and they generally result in bureaucrats making virtually all of the investment decisions.

This last point takes us back to mega-event planning. With key decision-making out of the hands of community participants, we risk more than just well-intentioned failure. Upgrade efforts become open to the accusation of being nothing more than maquiagem – “makeup” applied to conceal a deeper reality of neglect – or worse, a systematic eviction push through the backdoor of gentrification. Is the promise of “social integration” merely a guise for the process of improvement and displacement of residents in high value areas? That remains to be seen, but with the payday of the World Cup and Olympics just around the corner, the stakes have never been higher.