The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and Unplanned by Daniel Campo recounts the stories of those who frequented the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT), a vacant waterfront property in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York. Here, people were free to create their own recreational, artistic, and everyday experiences not made available or permissible in a typical park setting. Through improvisational interviews, observations, photography, and videography collected in the early 2000s, urban planner and associate professor Daniel Campo along with Brian Dworkin, Dan Wallenstein, and Brandon Beck study this informal park and the ways in which people mold and adjust the available environment to best fit their needs, whims, and unique desires. With this “do-it-yourself” model in mind, the author strives to create a dialogue between the vernacular and planned, the designed and undesigned, the deliberate and accidental.

The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and Unplanned by Daniel Campo recounts the stories of those who frequented the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT), a vacant waterfront property in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York. Here, people were free to create their own recreational, artistic, and everyday experiences not made available or permissible in a typical park setting. Through improvisational interviews, observations, photography, and videography collected in the early 2000s, urban planner and associate professor Daniel Campo along with Brian Dworkin, Dan Wallenstein, and Brandon Beck study this informal park and the ways in which people mold and adjust the available environment to best fit their needs, whims, and unique desires. With this “do-it-yourself” model in mind, the author strives to create a dialogue between the vernacular and planned, the designed and undesigned, the deliberate and accidental.

Campo chronicles the process of the site’s transformation into the East River State Park (ERSP) as it exists today, with the spontaneity of the waterfront’s ‘unpark’ dissolving into a formal urban space governed by a traditional set of standards, rules and regulations. The State Park’s office, governors, mayors, city officials, real-estate developers, industrial companies, a university, as well as residents and local activists were all at one point involved in the redevelopment process of the BEDT, fighting and planning for its grand and profitable future. During this same time, users and recreators were simply occupying the abandoned terminal in its present vacant form, reclaiming the site as a place for experimentation, creation, practice, and play.

There is a firm understanding that such a site cannot again be replicated elsewhere due to its particular evolutionary history and an array of external conditions, thus truly making it an accidental playground. Campo nevertheless uses the waterfront as an example for urban planners, design professionals, scholars, and citizens to consider the value of such informal, marginal spaces and encourages incorporating their incomplete and happenstance qualities into current public space design practices.

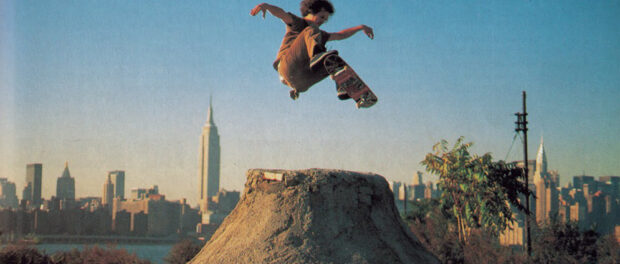

Over several chapters, Campo provides a personal perspective on the people he encounters at BEDT. The skateboarders, fire spinners, artists, filmmakers, locals, resident homeless and a marching band collectively appropriated the waterfront. Its expansiveness, remoteness, and cost-free anytime access provided them with an opportunity to do whatever they pleased, at their own risk. The insurgent mentality leads Campo to describe the waterfront as leftover space, other space, edge space, secret space, wild space, lost space, found space and outlaw space.

He argues that it is human nature to use and explore a place where access is prohibited or discouraged. As vacant places are typically undervalued and rarely recognized for their potentially vital qualities, Campo elaborates, “The unplanned stimulates our imagination and excites our innate desire for exploration, play, surprise and intimate interaction with the physical and social worlds that draw upon all of our senses and instincts.” Thus, an ethic of self-reliance is taught throughout each narrative, something that does not exist in the traditional urban park setting.

The ‘unpark’ demonstrates that everyday recreators can engage in their own place-making, sufficiently seeing to their own needs and desires without the interference of top-down planning forces. The waterfront demonstrates the value in interim planning, a build-as-you-go technique, one that embraces incompleteness and the unknown. BEDT thus satisfies the basic human impulse to “shape and reshape, to arrange and rearrange, and to destroy and rebuild.” Its users engage in constructive and destructive acts, exploiting nature’s pliability in order to engage in further creative spatial practices. Campo therefore encourages a move away from traditional Olmstedian landscape design and City Beautiful traditions, one that separates human activity and nature by lending towards a pristine ‘natural’ landscape meant to be enjoyed from afar. The Williamsburg waterfront encapsulates insurgent space, its informality giving way to multiple, simultaneous uses achieved through successful do-it-yourself design tactics and collective organization.

Campo notes that conditions on the ground are always subject to competing uses, and marginal conditions are typically temporary. As in the case of the waterfront, the underutilized parcel of land that boasted amazing New York City views would not stay undeveloped for long in a neighbourhood experiencing rapid gentrification. It was the result of several circumstances that New York state officials eventually accepted the accidental landscape of the terminal. However, the ERSP still fell victim to the dominant forces constraining its vernacular use and development including commodification, privatization, security, surveillance, and rigid programming. Strict governance and control in the name of risk prevention also limited the park’s social dynamic, causing it to lose its ad hoc qualities.

Similar characteristics of the terminal’s use in New York can be seen through the appropriation of Rio’s informal public spaces. Space comes at a premium in favelas, where the potential profitability of development outweighs the benefits of retaining an empty piece of land with its own potential to become a multi-purposeful civic space. As such, the existence of free space is usually temporary, meant to be enjoyed for a short period of time until it is again overtaken by another use. On one trip to Complexo do Alemão, I witnessed people occupying a parking lot that had been created after houses were demolished by the government as part of its scheme to widen the road. For now, amidst parked cars, it is a reclaimed leisure space where people set up plastic chairs to have a beer and a conversation, while children run around and play ball. Public spaces in favelas develop informally out of the leftover places in the urban landscape, and residents frequent them as part of their everyday experiences.

The waterfront, in its decaying abandoned state, provided a de-facto opportunity for people to construct, create, destroy and recreate the environment in a space lying outside the expectations and boundaries of the conventionally-ordered urban experience. This sense of freedom attracted the BEDT’s eclectic characters, and breathed new life into the terminal. The site combined random weird acts of fun, everyday life and accidental encounters, something that can spotaneously occur within informal spaces of favelas in the form of a street party. While creating an element of surprise and happenstance, the informal is inconsistent and Campo warns that it should not be romanticized. Nevertheless, he argues that ad hoc design elements should be incorporated into the formal design process. Leaving the “how” and “why” up to the park’s visitors creates opportunities for self-discovery and regeneration.

Since professional practices are typically geared towards completed and perfected design, Campo argues with the example of BEDT, that there is something to be learned from the vernacular as well as incremental design technique. This collection of narratives adds to the literature on informal public spaces and the value of the unplanned urban form in cities.