On the pitch at the very top of favela Santa Marta, a group of kids play a spirited game of soccer, dribbling and shooting to the sound of bumping funk music. Green netting stretches overhead, covering the pitch and catching any stray balls before they can sail into thin air. A few kids perch on a nearby roof, flying kites.

Besides recently hosting the Copa Popular (People’s Cup), this soccer field is home to Escola Bola (Ball School), a program that provides free soccer lessons to kids in Santa Marta. Escola Bola was originally instituted by the State government as part of UPP Social, the bundle of social programs that accompanied Santa Marta’s Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Santa Marta in 2008. There are currently 38 UPPs installed across Rio’s favelas. While heavy criticism of police brutality has overshadowed the program’s initial premise, Santa Marta’s UPP has been primarily well-received. Police officers and residents are on good terms, and officers sometimes join in on soccer games with the kids.

In 2008, after overseeing the soccer pitch’s construction, the State government hired José Luiz de Oliveira to head the program, offering soccer lessons Monday through Friday. From kindergarten-age kids just starting out to teenagers with a real knack for soccer, the program served 100 youths from the community with sessions divided by age group. It was a great success.

In 2009 the State abruptly cut all funding for the program. José’s R$600/month salary dried up without warning. With many of Santa Marta’s kids now depending on the soccer lessons that Escola Bola offered, José decided to keep the program going, with or without State funding.

“It’s what I love to do,” he says. “I’ve had others to help me. I don’t have my own kids to support and I’m not married, so it’s worked out somehow.”

For the next year and a half after the funding was cut, José continued to give lessons with no financial compensation besides small contributions from the students’ parents.

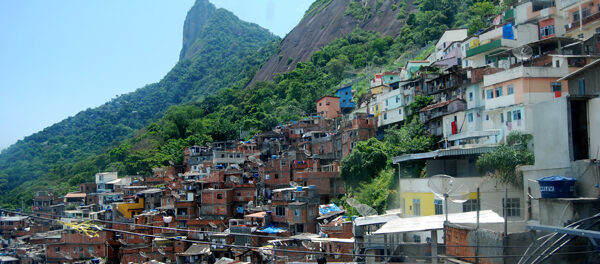

Unlike most of Rio’s other pacified favelas, situated far from the public eye in the North Zone, Santa Marta has always had unusual visibility by virtue of its location. Situated right above Rio’s wealthy South Zone, Santa Marta climbs up the steep slope towards Corcovado, looking out the middle class neighborhood Botafogo and Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon.

Besides visibility due to its centrality, Santa Marta has received widespread media attention ever since Michael Jackson’s “They Don’t Care About Us” music video was filmed in the favela. The combination of physical proximity and media visibility has resulted in a far higher level of government support and investment in Santa Marta than in nearly any other favela in Rio.

Despite this, neither the City or State government has stepped in to fill in the gap in funding left by the State.

“There have been promises, outlines for City projects, but so far, nothing,” explains José.

Funding was coming from the State of Rio de Janeiro, which has a less rigorous monitoring system than the city. At the state level there is little accountability for projects such as Escola Bola in the years after they have been established.

“The City has to register everything, but the State doesn’t keep a registry. There’s nothing binding.”

José had hoped to get enough visibility during the World Cup to gain the funding back but so far the program’s only income comes from non-profit organizations and Santa Marta’s own residents. A Brazilian NGO called Alfa stepped in last year to help foot the bills, and is now covering most of José’s former salary. The lessons remain free for all the kids, though some parents still insist on contributing.

While Escola Bola is a soccer program that builds technical skills, its larger goal is to have a broadly positive impact on the lives of the favela’s youth. José says he is not interested in forming professional soccer stars, but teaching kids how to be good citizens.

“Above all, I want to form citizens. The kids need to know their rights, their duties. They need to learn how to defend themselves, to respect their parents, to respect their peers, to avoid becoming obsessed with grandeur. I’m trying to pass on these kinds of values.”

The program has had several small victories lately. On July 10, Escola Zico 10, the NGO of former soccer star Zico, hosted COPA SOC14L, a soccer tournament between teams from 8 pacified favelas. After the competition, the organizers decided to donate the synthetic turf used in the tournament to Santa Marta’s soccer field. Before the donation, the turf was “done for, uneven, causing accidents for our athletes.” The field hadn’t received any maintenance since the 2008 investment.

Manuel Gonçalves, Rio’s Secretary of the Ministry of Sport and Leisure, announced the donation. According to the article on Zico 10’s website, Gonçalves “was very pleased to see more young people being able to receive quality sports equipment.”

There was no mention of the fact that the lack of government funding was the reason for Santa Marta’s deteriorating equipment in the first place.

José and his friends hauled the turf up to the top of Santa Marta themselves, removing the old and installing the new without any glue. The NGO donors and the Government failed to provide any adhesive for the new turf, so the squares lie dangerously loose on the field. Escola Bola is now waiting on three buckets of glue promised by another NGO to finish the job.

Throughout our short interview, José pauses to greet passing neighbors and throw glances back towards the pitch, keeping an eye on his students. Night has fallen, but since the lights that normally illuminate the pitch are not working, class is cancelled for the evening.

José’s popularity with the kids is evident, as is his commitment to the program. The combined forces of José, Santa Marta residents, UPP officers, and various NGOs like Alfa and Escola Zico 10, have kept Escola Bola afloat so far. Without any government support, though, Escola Bola has no guarantee of long-term security, something the kids from Santa Marta who depend on the program clearly deserve.