Historically defined as communities of fugitive slaves, quilombos represented areas of resistance and freedom for Afro-descendent Brazilians in the last country in the Western hemisphere to abolish slavery. Under the 1988 constitution, following calls from black activists for recognition and reparations, descendants of quilombos gained the rights to the land they had historically occupied. Despite this, the struggle for territorial rights is still ongoing in Rio’s two official urban quilombos.

While largely thought to be a symbolic gesture designed to appease the black movement, the legislation laid the groundwork for thousands of claims for recognition and land rights, resting on the emergence of a new legally designated ‘quilombola‘ identity, passed into law under Lula’s government in 2003. No longer restricted to communities who could prove historic ties to settlements of escaped slaves, a collective identity grounded in black ancestry, resistance and territory, became the key markers by which groups could claim quilombo status.

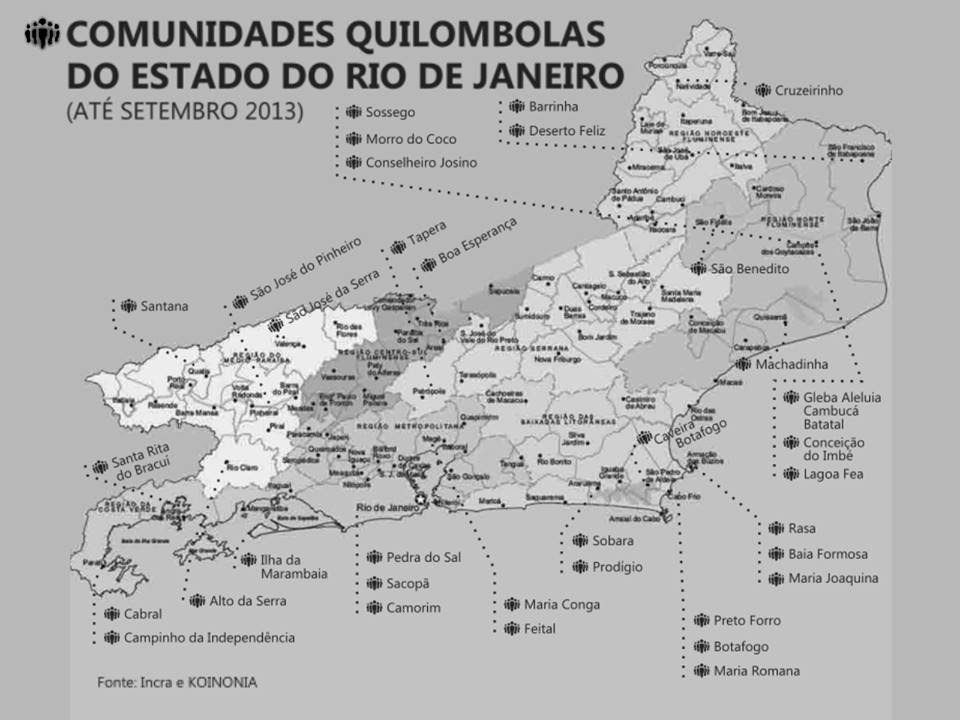

Though official recognition has for many of these groups been forthcoming, gaining land rights has proved an arduous and endless process for most. According to the Fundação Cultural Palmares, the government body responsible for certifying the communities, Rio de Janeiro state has 29 officially-designated quilombos. However, only two so far have successfully gained the rights to their territory as enshrined in the constitution.

Quilombo Sacopã

According to Luiz Pinto, leader of the Quilombo Sacopã and President of the Quilombo Association of Rio de Janeiro State, urban quilombos face specific challenges in gaining territorial recognition. This, he suggests, stems in part from the notion of the quilombo as a secluded rural haven for slaves to hide in. From this, legal definitions have evolved which are yet to seep into the wider public imagination. In addition, he points to the powerful interests at play in the urban context, particularly in Rio de Janeiro where soaring real estate values and attempts to sanitize wealthy areas of the city have, for many years, displaced its low-income residents.

In the case of Quilombo Sacopã, perched over the exclusive Lagoa, such difficulties have been accentuated. “Racism is heightened for being in a place where we are told we do not belong,” Luiz explained. Indeed, the luxury flats which sprung up around the quilombo in the 1970s house some of the city’s most wealthy and powerful. These include members of the state’s judiciary who have engaged in a long battle to get the quilombo removed.

Having occupied the area for over a century, the 30 family members who make up the community have for over four decades resisted successive attempts at eviction. As part of this struggle in 1999 the community was granted quilombo status, initiating another judicial process to obtain rights to their land, still ongoing fifteen years later. However, Luiz believes that by the end of the year the territory could be awarded, having entered into the final stages of the process. Yet he also remains sanguine, pointing out that many quilombos at this stage in the federal recognition process have seen their claims stagnate for years.

The quilombo faces challenges other than eviction. Since 2013 they have been banned from holding their popular samba and feijoada, which for over 40 years has been a cornerstone of the community’s identity and livelihood. The judicial order prohibiting the event states commercial activity is not allowed in the area, yet Luiz points out that it has not been applied to other businesses operating in the local community–“it only counts against us”.

Facing the threat of prison if he continues with the feijoada, Luiz has been fighting to get the case heard through a civil public action, which should get underway shortly. Despite coming face-to-face with the corruption of the judicial system in previous legal processes, he believes that their case will prevail, arguing that the injunction is illegal as it contravenes the constitutional guarantee of freedom of cultural expression for Afro-Brazilians.

Quilombo da Pedra do Sal

Meanwhile, the Quilombo da Pedra do Sal has faced similar struggles against powerful interests in Rio’s port zone. Their fight for recognition began in 2004, when the Catholic Church raised rents in the area, evicting many of the poorer tenants who could no longer afford the rent. In the area once known as “Little Africa,” where samba carioca was said to have been born, they argue for the rightful presence of a quilombo community to guarantee the maintenance of Afro-Brazilian traditions such as Candomblé and samba in the area.

Indeed, for many Pedra do Sal is already a synonym of ‘samba.’ The twice weekly gatherings are hugely popular with locals and tourists alike. Yet for the quilombolos, these events fail to to transmit the rich heritage of the area, grounded in its black ancestry. What’s more, under the pressures of state-led regeneration, the Port Zone is changing fast, and amid rising property prices it remains to see what will become of the region’s less well-off inhabitants.

Yet in a significant victory for the quilombo, it has recently been awarded status as an area of cultural protection by the City government. For Luiz Torres, Director of the quilombo’s association, it signals an important step in removing the obstacles to gaining land rights. However, he warns that the slow process of titling is on hold across the country because of the upcoming elections.

The article that defines the quilombo is itself under attack, with many challenges linked to the powerful agro-business lobby. They argue the article is unconstitutional as it undermines the principle of private property, offering the opportunity for millions to claim ownership of the land they occupy. Such opposition is not going unchallenged. Damião Braga, President of Pedra do Sal’s Quilombo Association, is involved in the national quilombo network, who is currently lobbying to protect these rights, which have allowed for the recognition of over one million of Brazil’s poor majority as quilombolos so far.

Where once quilombos struggled against an explicitly racist slave-holding regime, today their fight continues in a state plagued by the legacy of this injustice. It remains to be seen whether in the face of such an obstructive process for obtaining the rights guaranteed under the constitution, the quilombo movement can offer the broader politics of reparation that it aspires to.

In the meantime, Rio’s two urban quilombos continue to display a well-spring of resistance in the city, that might serve as inspiration for others.