This is Part 3 in a five-part series documenting Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Installations.

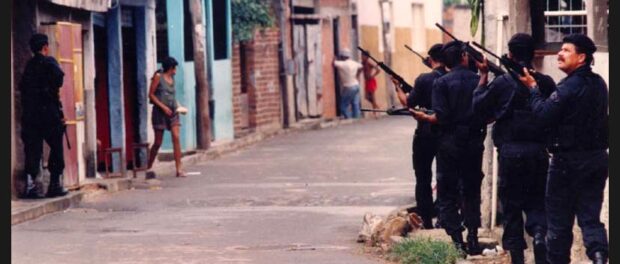

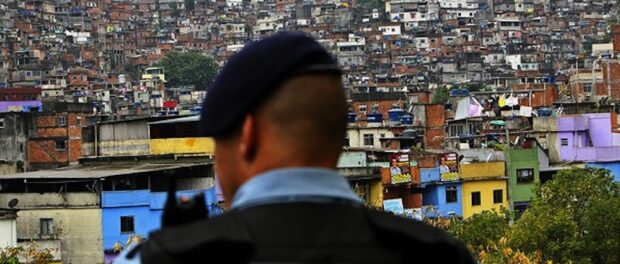

Head of the UPP, Frederico Caldas, admitted in an interview with BBC Brasil that the next phase of the UPP was improvization, a reaction to attacks on the police in late 2010. Complexo do Alemão, a sprawling complex of favelas considered one of the most dangerous parts of the city, was targeted by policymakers in an attempt to strike at the heart of the drug trade. In November 2011, 2,700 police officers from various forces moved into the favelas in a mega-operation designed to clear the path for UPP implementation. In all, 8 units were added in Alemão and neighboring Penha between April and August of 2012. The pacification of Alemão initially did great things for the reputation of the UPPs. It marked the moment at which the wider society began to believe in the program and the state’s commitment to seeing it through. The sight of drug dealers desperately escaping police occupation reinforced the idea that the tide might be turning.

However, inevitably, pacification has not been so simple, and in August 2014 Caldas stated that Alemão represented “the biggest challenge” facing the the UPP program. Between continued police violence and the determination of traffickers not to concede territory peacefully, it is clear that in Alemão things have not gone smoothly.

Bookending the pacification of the Alemão and Penha areas were two significant UPP implementations in South Zone. Firstly Vidigal, which since receiving a UPP has seen huge investment and rapidly increasing gentrification. Then Rocinha, the biggest favela in Rio and, like Alemão, a traditional stronghold of the Red Command. Rocinha has experienced many of the same problems as Alemão, and it is debatable whether pacification has made community residents feel safer.

19. Vidigal — South Zone

Date of installation: January 18, 2012

It is no secret that pacification in Vidigal has had a huge impact on the community. The higher reaches of the favela, with their stunning views, now play host to parties attracting the city’s middle and upper classes. Tourism is flourishing and there has been a huge amount of investment—both foreign and national—by entrepreneurs hoping to cash in on the boom. In the absence of regulating for affordability in housing, gentrification is an inevitable effect of the South Zone UPPs, and despite residents chronically critical of the lack of accompanying investment in sanitation infrastructure and other public services, in the long run many are likely to be priced out. In Vidigal this process is already well underway. The President of the Residents’ Association has estimated that 30% of the favela’s population are new there. Even when locals can afford to stay, many feel uncomfortable at the new dynamic of the favela, as highlighted by the 2014 Fala Vidigal debate series.

Resident Perspectives

“I’d like to know why the community can’t have parties in their houses, why they have to finish at a certain time. The teenagers in the community don’t have a place to hang out, to dance, they don’t have a place to play. The (new venues marketed to outsiders) at the top the community, which charge R$80 or R$90, stay open until 3am and nobody stops them.” – Ivanete Alleluia, Member of Vidigal’s Women’s Association

“The police needs to be demilitarized urgently. We don’t need to stop them altogether, of course, but the way they act needs to change, as do their working conditions and pay. The hatred of the police is not against one or another guy on duty on your street, but rather it is directed towards the institution of the police, as a whole, which is not credible at all. At the same time, do what has to be done: truly make the favela a part of the city, with rights to sanitation, education and health. But, to be honest, I don’t think this is going to happen.” – Mariana Albanese, Journalist and editor of Vidiga!

20. Fazendinha — North Zone

Date of Installation: April 18, 2012

In this area of the North Zone there is a strong sense that what is happening is not community policing. Reports of abuse of power by the UPP have been frequent, and residents claim they are targeted simply for being from Alemão. Just four months after implementation in Fazendinha, residents accused UPP officers of kidnapping locals and holding them for ransom, all under the knowledge of the local commander. Then in November 2012 Mario Lucas de Souza Pereira was shot dead by plain-clothes police officers after an argument at the community football pitch. Pereira’s death led to the creation of the Ocupa Alemão collective, which fights against the criminalization of public space in the favelas.

Though incidents of abuse make it hard to sympathize with Rio’s police force, the UPP officers do have a difficult mandate in Fazendinha. Echoing typical complaints from Alemão, in this video a Fazendinha officer laments working conditions, highlighting that there is not even running water for officers to wash their hands. As it affects residents, this lack of infrastructure inevitably affects officers’ morale, exacerbated by the high levels of stress involved in their work.

Resident Perspective

“They pacified our hill, but there is absolutely no safety. I’m a worker, my children are workers, and what safety can the UPPs offer us?” – Alberto Silva, Fazendinha Resident

21. Nova Brasília — North Zone

Date of Installation: April 18, 2012

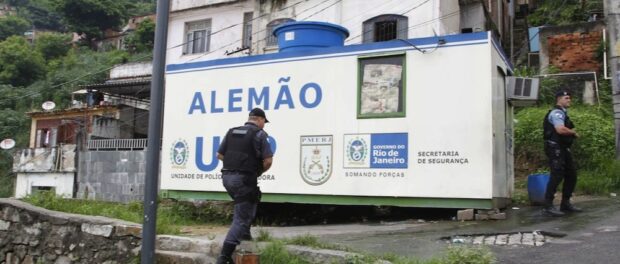

Pacified on the same day as Fazendinha, Nova Brasília has had a UPP experience plagued by violence. The community earned the unwanted distinction of being the first favela in which a UPP officer was killed. Just three months after implementation drug traffickers attacked the UPP container, killing Fabiana Sousa who was crossing the road to the bakery. In September 2014, Nova Brasília‘s Uanderson Manuel da Silva became the first UPP commander to die. On December 8 four officers from the community were injured in shootouts. It is one of the great conundrums of the program: community policing should involve less heavily armed police than in the past (and there have been moves towards that). One justification given is that this remains difficult while criminals possess military-grade weapons.

However, it just takes one look at the Facebook group page of the Nova Brasília UPP to see that pacification through community policing is perhaps not foremost on officers’ minds. In 2013 Wallace de Souza, 21, and Joseph Alexandrino, 19, were killed by UPP officers, with residents describing the incidents as executions. In October 2014 Marcos Vinícius Soares Heleno, 17, was shot and killed as he was unloading a truck; police claimed he was carrying a weapon but his family strongly refuted this version of events. Also in 2014, 72 year-old Arlinda Bezerra das Chagas was shot by a bullet which residents say came from UPP officers. Further worrying news emerged in September 2014 as the UPP set up a base inside a community school and photographs showed officers brandishing rifles in the playground.

Nova Brasília has received a public 3D movie theater and many new commercial ventures (including a bistro specializing in artisanal beers) that underscore the potential of the UPPs to bring in new investment. However, police violence and the ongoing presence of drug gangs continue to overshadow positive news from the community.

Resident Perspective

“How is it that we will live here with only the police? We need to occupy the minds of the youth. Where are the schools, hospitals? … They have just done a make-over here. In reality, the life of residents has worsened, as this police force believes we are all bandits, and treats us as such. Enough! The (Alemão) Complex has woken up, and will not accept these murders any longer. Not from traffickers, and not from the police.” – Robert, pastor and community leader

22. Morro do Adeus/Baiana — North Zone

Date of Installation: May 11, 2012

One of the few positives to come from the pacification of Alemão communities is that, apart from a few individual days in recent months, schools have not had to close their doors. Before the UPPs it was common for schools to shut for lengthy periods of time—in 2007, 4,000 children suffered two months without school—because of violence between police and drug gangs. This is now a rarity, and schools are able to teach the entire curriculum with little interruption, a fact that an Adeus UPP commander highlighted in his appraisal of the program. Additional education projects facilitated by pacification—such as Mais Leitura in Morro do Adeus—are extremely important for the UPPs’ wider success and legitimacy, yet they are rare. It is widely conceded that UPP Social, created to deepen social inclusion in pacified favelas alongside the police units, has been an overwhelming failure. It has since been replaced by Rio+ Social with the jury still out on whether that will be successful. Public security expert Dr. Ignacio Cano argues that in most areas the UPP is solely a policing program.

Morro do Adeus and Baiana have not had the same level of conflict between police and residents as in other parts of Alemão, but it is clear that the UPP is struggling in its effort for control of the territory: it has been widely reported that the Friends of Friends gang has a stronghold on the favela after taking over from the Red Command.

Resident perspective

“It seems as if nothing has happened, doesn’t it? We are already used to much worse. But I shiver just thinking that all this (police occupation) has not changed anything.” – Maria Eugênia dos Santos, 61, resident, speaking after a shootout

23. Morro do Alemão/Pedra do Sapo — North Zone

Date of Installation: May 30, 2012

In June 2014 Lucas Gustavo da Silva Lourenço, aged 15, and Gabriel Ferreira Mendonça, 17, were shot dead by police officers during a shootout in Morro do Alemão. According to his family, Lucas was a quiet boy who spent most of his time playing videogames and was just returning from a game of football. Lucas’ family was denied access to the body, which was dragged along the ground and dumped in a police van. Brutality of this kind betrays the idea the police are working to serve residents. As Lucas’ cousin highlights below, UPP officers are largely unprepared for working in favelas. With the program scaling too quickly, young recruits with little or no experience are put in delicate situations or, on the other extreme, without enough new officers, those already part of the “old way” of doing things are used. UPP training lasts little more than 6 months, while experts suggest a minimum of 12 months is necessary to train for community policing.

In Pedra do Sapo, the UPP container—which is not bulletproof—has been frequently targeted by drug factions. A recent attack forced officers to hide behind refrigerators. Individual officers’ names have also been daubed on walls of the community, marked for death. Indeed, one of the early complaints of UPP officers was that they did not have the equipment and protection necessary to carry out their roles, factors which naturally affected officers’ motivation and sense of identification with the program.

Resident Perspective

“Unfortunately, this is the lack of preparation of our police. Those who they should be chasing, they aren’t. They know where the criminals are, they just don’t go there because they know they will encounter resistance, so they come where there is no resistance and do what they did to my cousin and his friend. With only six months of training, nobody, no one can become a police officer. That training is ridiculous.” – Cousin of Lucas, injured in the same incident

24. Fé/Sereno — North Zone

Date of Installation: June 27, 2012

In Fé and Sereno, located in the neighbourhood of Penha, the UPP has been received in a less hostile manner. In fact, in 2014 the local commander, Leo Luldoff, was nominated by community leaders and residents for a Medal of Honor, the highest decoration in the state. In the same ceremony, two of his officers were also recognized for their work in the community, including Raquel de Azevedo Araújo who ran vacation activities for children. When UPP officers take the initiative to organize events in their communities, they can challenge the idea that the UPP is solely about policing; however, such examples are hard to come by, particularly in Alemão and Penha. Because the UPPs have very limited control of these vast areas, it has been impossible to implement proximity policing throughout.

Resident Perspectives

“I was born and raised here in the community. Before there was nothing for residents. If anything happened on the hills, it was in the South Zone. Today we have a different reality. Society is recognizing the community.” – Claudia Gomes, resident

25. Chatuba — North Zone

Date of Installation: June 27, 2012

Having received praise for his work in Fe and Sereno, later in 2014 Leo Luldoff was moved to Chatuba where he found himself in the spotlight again, this time for the wrong reasons. He signed a document ordering officers in the community to remove bullet cases in incidents in which shots were fired. This has worrying echoes of pre-UPP policing, where transparency and accountability were huge issues and police went to great lengths to ensure they could not be held responsible for human rights violations. A further controversy to hit Chatuba occurred when officers were filmed throwing homemade explosives in the street, seemingly without motive.

Resident Perspective

“We were on Street 9 when we were approached by 4 police officers who were completely rude to us. They began to get violent as soon as they arrived.” – Unnamed resident

26. Parque Proletário — North Zone

Date of Installation: August 28, 2012

Parque Proletário in Penha has seen heavy violence since UPP implementation. In 2013 residents accused UPP officers of killing Laércio Hilário da Luz Neto, 17, found dead on the roof of a house, although the autopsy held he was not murdered. Three buses were burnt in the subsequent protest, and officers were attacked with rocks. In February 2014, UPP officer Alda Castilho was killed and three others were wounded. The day after, Military Police slaughtered six youths in an unpacified favela, Juramento, with graphic photographs showing the boys laid out on steps of the favela. This inconsistency—in the tourist-friendly areas there is pacification (of sorts) while further north a war mentality still pervades—is one of the reasons the UPP is destined to have only a limited impact.

Officers speak of their fear while patrolling the streets of Parque Proletário (particularly an area known as Street 29), with past attacks on police seeming completely unpredictable in nature and timing. At the time of the attack that killed Castilho, officers estimated they were being attacked every two or three days. Officers also complain that they work 12 hour shifts—which are often extended—with only 36 hours off. They argue that due to the tension and stress involved in working in the favela, time off should be increased to 48 hours. It is a reasonable request in an area that is one of the more dangerous UPP posts in the city.

Resident Perspective

“What we hope for is partnership with the police. Today we are not going to see the police as the villain of the story, we want to see the police as our partners… It has improved a lot. I’m doing an interview with you, before I couldn’t!” – Robson, community leader

27. Vila Cruzeiro — North Zone

Date of Installation: August 28, 2012

Vila Cruzeiro, connected to Parque Proletario by the aforementioned Street 29, was the final favela to be pacified in the Alemão and Penha neighborhoods. The Brazilian Support Service for Small Businesses and Micro-Companies (Sebrae) visited Vila Cruzeiro to implement Comercio Legal, a UPP-supported project aiming to legalize businesses in the area. With 70 business owners in attendance at the first event, it was an indubitable success and showed that the UPP can have a wider social impact.

Nevertheless, as in almost all the favelas in Alemão, police violence and the continued presence of drug traffickers has led residents to question whether the UPP has made substantial improvements in the community. In March 2012, just before UPP officers moved in, officers from the Pacifying Force were accused of taking a 22-year-old into the forest, tying him to a tree and breaking his arm. More recently, the week before carnival in 2015, moto taxi driver Diego Algarves was shot in the back and killed as he drove home from a party, in what José Beltrame described as a “disastrous” police action.

Resident Perspective

“It’s really sad. It’s been confirmed that when [the police] were searching for people and entering houses that were empty, they went in, broke everything, and there are reports from some people that things disappeared. Mobile phones disappeared, money disappeared. It’s really sad that people go to work, earn their money, and this happens.” – Nilton Gomes, community leader

28. Rocinha — South Zone

Date of Installation: September 20, 2012

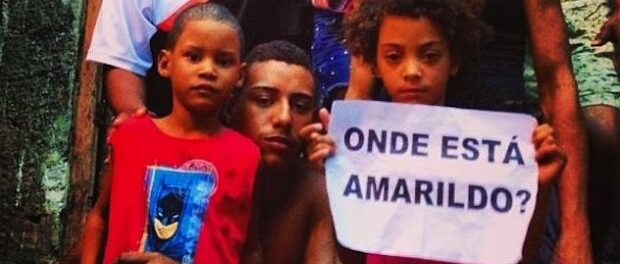

By far the most brazen, shocking example of police abuse comes from Rocinha. The heart of the Red Command’s operations, the implementation of a UPP in Rocinha was always expected to be one of the biggest tests. However, the challenge has become even more intense since the murder of bricklayer Amarildo dos Santos in 2013. In a case which gained national and international notoriety, Amarildo was tortured for 40 minutes by four UPP officers before being dumped in the surrounding forest. His body has yet to be found. As the story unfolded a total of 25 officers were accused of involvement, many of whom were aware of the torture but did nothing to stop it. This was perhaps the moment that public opinion around the UPPs shifted: as national media began to print stories of abuse they had previously held back, policymakers could no longer rely on the rhetoric that the pacifying police force was implementing a new philosophy. Rocinha residents commonly complain of torture, threats, and invasions of their homes, and many attest to feeling less safe now than they did before pacification.

Resident Perspectives

“I wish Rocinha’s only problem was that of security. Here we lack the most basic services.” – Carlos Eduardo Barbosa, community leader

“Before, we knew we had one armed power and we could walk in peace. Now, there are two powers and at any moment we could be in the middle of a conflict. When I see how Rocinha is now, I am sad. The UPP died when Amarildo died, and Rocinha’s situation is similar to that of Complexo do Alemão. I pray and believe that Rocinha will get better.” – Eliana, resident

This is Part 3 in a five-part series documenting Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Installations. For other articles in the series click here.