Last week, hundreds of people in Complexo do Alemão marched to call for an end to violence in their community. The march followed 24 hours during which at least five people were shot dead, including 10-year-old Eduardo de Jesus Ferreira, shot on the doorstep of his house by a policeman.

The state of urban violence in Brazil is alarming. According to the Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice, an advocacy group based in Mexico City, 19 of the 50 most violent cities in the world are located in Brazil. This list includes cities such as Porto Alegre, Recife, Salvador, and Fortaleza, where the murder rates per capita are as high as 79.4 per 100,000 residents. Even more worrisome is that violence in Brazil is not only conducted by citizens; as seen with recent events, it is often carried out by police forces.

In 2012, 1,890 people died during police operations Brazilwide, an average of 5 deaths per day. In the state of Rio de Janeiro alone, 362 people died at the hands of the police, or an average of 1 death per day. In 2013, roughly 424 people were killed by police in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In the first six months of 2014, 285 people were killed by police in the state of Rio. At this rate, the full year of 2014 would have ended with roughly 570 deaths by police. While we wait for final figures, it’s clear homicides in Rio are increasing. The Brazilian Forum on Public Safety reports that, between 2012 and 2013, there was a 15.1% increase in homicides in general, from 4,081 to 4,745, nationwide. Comparing these two pieces of data, deaths at the hands of police comprised about 10-12% of all homicides in Rio de Janeiro in these two years. And of deaths of children at the hands of police in the past decade, 60% of those nationwide were in Rio alone.

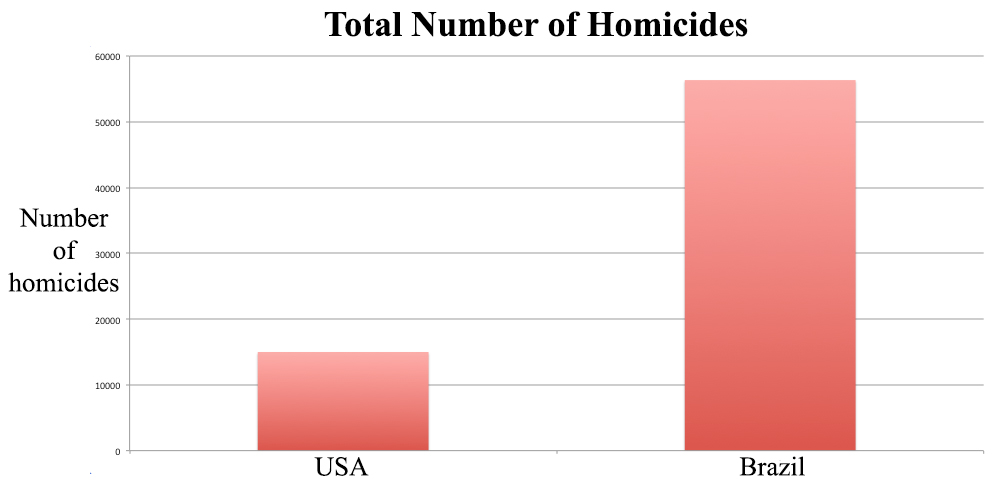

In comparison to other countries, including the United States, the death rate at the hands of the police is much higher in Brazil. Between 2003 and 2009, in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo alone the police killed more than 11,000 people during arrests. In contrast, in the entire United States during the same period roughly 4,800 people were reported to have died during arrests. Fatal violence in general is higher in Brazil too. In 2012 56,337 people were murdered in Brazil, whereas in the United States, a country with a population 60% greater, less than 15,000 people died violently. And whereas in the United States 1 person is killed by police for every 37,000 arrested, in Brazil the same figure is an appalling one person for every 23 arrested.

With death at the hands of police comes torture. Recent reports from both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International reveal torture as a chronic problem in Brazil. In the 1980s Brazil signed and ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, a principle of customary international law every country is expected to abide by, but recent events reveal that the country is far from eradicating torture. One of the most publicized cases of torture at the hands of police was the case of Amarildo Dias de Souza, who was taken by officers from the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Rocinha in July of 2013 and was tortured to death with electric shocks and asphyxiation.

Another serious police issue has been the use of excessive force to quell public protests. These actions have garnered international attention during mega-events like the World Cup in 2014 and in the build-up to the Summer Olympics in 2016. These attempts to suppress free speech and free press are violations of human rights. Police have attempted to stop reporters and citizens from photographing or recording protests on numerous occasions, since photos and videos would serve as evidence of abuses if and when they occurred. Despite international attention on these issues, the police continue to suppress these rights in favelas and other communities.

The mega-events provide an excuse currently being used by police to become more militarized and abusive, especially with regard to favelas. Recently the National Coalition of Popular Committees against the Cup (ANCOP) released a Dossier on Mega-events and Human Rights Violations in Brazil–2014, with data revealing how the Military Police force works in favelas using the pretext of these events. For example, on July 24, 2013 during the Confederations Cup, Military Police forces went into Complexo da Maré and executed 10 people in the span of two days. Less than a year later in April 2014, the Armed Forces began a long-term occupation of Maré and 16 people died and 162 were imprisoned in a span of 15 days. The State is using mega-event security as a pretext to occupy, repress, imprison, and kill community members.

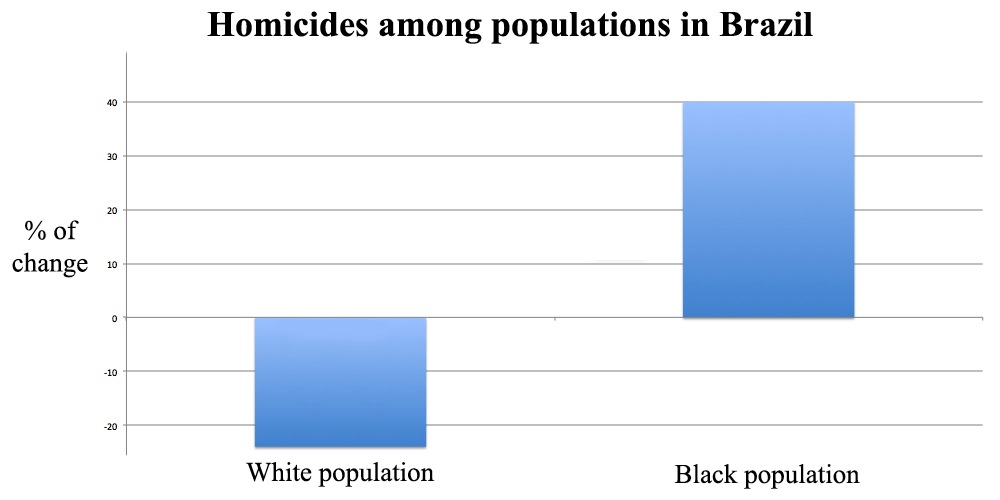

A further exploration of the facts and statistics of human rights abuses in Brazil reveals that racism often shapes these abuses. Just in the past few months, a New York Times article illustrated how institutional racism is alive and well in Brazil, long after the brutal and prolonged period of slavery ended, while an NPR article highlighted that in recent years homicides among whites in Brazil have decreased by 24%, while homicides among the black population have increased by 40%. Another study reveals that young black men are 2.96 times more likely to be victims of fatal violence than their white counterparts.

On a Rio de Janeiro Military Police officer’s shoulder comes emblazoned the logo from their 1809 founding: the crown, sugarcane and coffee. The crown represents the State’s police establishment to protect the monarchy a year after Napolean’s army sent the Portuguese crown packing to Rio de Janeiro, from which they governed their territories until it was safe to return home. Sugarcane and coffee represent the private property those officers were charged with protecting, and the slaves they were charged with capturing as they attempted freedom.

Fast forward to 2015–with no major attempt at reform–and Rio’s Military Police continue committed to the same mission, in its modern equivalent: protecting an elite establishment, protecting private property, and criminalizing Afro-Brazilians. 60% of favela residents in Rio are Afro-Brazilian. It is no coincidence that these communities are where the Military Police forces are the most abusive. According to Rio’s lead public defender, Nilson Bruno Filho, the only Afro-Brazilian lead public defender in the nation: “There’s a saying that black meat is cheaper. People don’t get shocked to see a dead black person because the person in their minds can be linked to crime. And in Brazil, if a person is linked to a crime, they can be killed.” The current state of police brutality in Brazil is rooted in deep societally conditioned and institutional racism, where low-income Afro-Brazilian youth are most at risk, and children can be killed for simply playing on their doorstep.