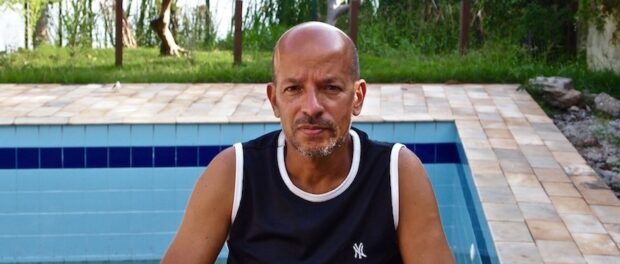

Sitting in the rubble of his neighbor’s demolished house on Sunday, April 5, Tadilmarco Peixopo, the last resident of Avenida Autódromo, described his surroundings of debris and vacant lots as a war scene: “It is as if you were living here and a bomb fell on the house next door and killed everyone, leaving you all alone. It is like the end of the world and everyone died.” Just eleven days later, on April 16, Tadilmarco received word from a lawyer that the City was going to demolish his house, and the house of one other resident, “immediately.”

21 years ago Tadilmarco moved to “the best place to live in Brazil. It was called Avenida Autódromo.” Originally a community of fishermen settled in the 1960s, Vila Autódromo, in Rio’s West Zone, grew to 3,000 residents. That number now stands at around 50 families. For 20 years Vila Autódromo faced threats of eviction and fought hard to receive 99 year leases from the State government; however, the 2009 decision that Rio de Janeiro would play host to the 2016 Olympic Games further jeopardized this small community due to its location next to the planned Olympic Park.

Tireless community resistance won some residents deals at or near market-rate compensation—the first in favela history, although the market-rate value has been disputed—in exchange for leaving their homes. But the already tense situation escalated on March 19 of this year when Mayor Eduardo Paes used eminent domain to announce the eviction and demolition of the remaining 58 houses for public use, leaving those who have resisted most vehemently based on the Mayor’s promise of allowing those who wanted to stay to remain and receive infrastructure improvements, hopeless. This recent move that Tadilmarco described as a “cowardly act” appears to have sealed the fate of Vila Autódromo: “I do not believe people will manage to carry on living here. [Paes] has no interest in leaving anyone living here. So Vila Autódromo is over unfortunately. It is a reality that I, who live here, have to accept bitterly in my heart. It is very difficult to admit.”

Most disappointing is that the policy of declaring eminent domain to justify taking private property for public use is at odds with previous promises made by the Mayor and the Olympic Committee.

For years the community has received contradictory promises from the government. In 1994 they were granted 99-year land titles from the State, in 2009 the original plans for the Olympic Park left Vila Autódromo intact, and in 2013 the Mayor promised that no residents would be forced to leave.

Tadilmarco recalled: “The mayor declared, not just in one meeting but in various with the community and the president of the Residents’ Association, that whoever wanted to stay could stay and that he would improve the infrastructure. Moreover, that if someone were to have to leave their home, they could be relocated within the community.”

“That was just a lie…Like a good politician, used to lying, he is trained to lie, so he came in with this eminent domain.”

Even before this announcement of “expropriation via decree,” Tadilmarco had doubts as to whether supposed market-rate compensation was the fair and respectful policy it was reported to be. “If my house is not for sale then it doesn’t have a price. It can’t be valued by the market. If I don’t want to sell something of mine, then it doesn’t have a price.”

The city has made offers for Tadilmarco’s house, but they have yet to make one that he considers just. “I have not accepted and will not accept if it is not a fair price. I will stay until the last consequences. I hope it reaches a fair price for me and my family.”

He believes a fair market value is one with which he can “take that money and buy another property in Barra da Tijuca, as they are now calling this area, on the lakefront, with this much space, with the security and tranquility of this area.” This, he claims, he cannot do with the price he was being offered.

“It was not a good price—it was a bad price. The City didn’t pay well; it simply shut people up.”

He explains that most families have accepted the City’s offers as much out of fear as for the money.

Tadilmarco feels especially strongly about the subject because, he said, it is not the first time he has had something taken away by the City, and specifically by Eduardo Paes who, from his time as Deputy Mayor for Barra da Tijuca, has a long history with the community.

“The mayor, Eduardo Paes, took my job away four times. He took the first job I had, a company, all properly documented. He arrived there with the municipal guards and two trucks and knocked down my business. I was left with a family in need; I even went hungry because I could not get a job. Later, I put together another business and then Eduardo Paes went there and took it away for the second time. So I took to driving competitively on the racetrack. Then Eduardo Paes and Cesar Maia closed the racetrack and left me without work again.”

“I got a taxi and earned a living as a driver spending 18 hours a day driving around. I got kidnapped in Rocinha by 16 gangsters. I didn’t see my son grow up because I would leave the house at six in the morning and come back at four the next morning. I had to work long hours to pay the rent because the car was very old. I got back into racing and for the fourth time he took my job. Now he wants to take my house.”

Since hearing from a lawyer on Thursday that his house could be seized imminently, Tadilmarco said he is urgently seeking somewhere to move his family. He reported that the damage to his neighbor’s house had damaged his house too, and that he now feels unsafe in his own home.