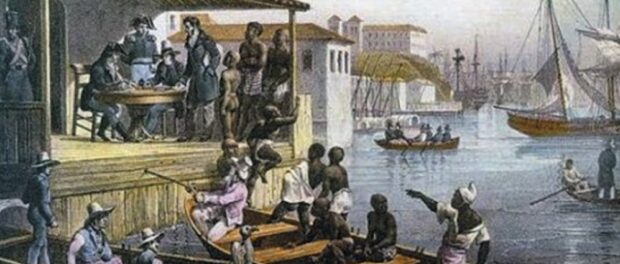

In 1807, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed an act abolishing the international traffic of enslaved people within the British Empire. Much of the pressure to pass the act had come from religious groups led by the Quakers, who had in 1787 begun a humanitarian crusade against slavery, based in liberal values of freedom and the idea that all men are born equal. However, there were a variety of factors which led Britain to eradicate a system that had brought it considerable profits (it is estimated that Britons transported 3 million Africans between 1700 and 1810), one of which being that slavery no longer made economic sense, as the Industrial Revolution was flourishing with free trade and labour.

Following abolition in Great Britain, British abolitionists began targeting other nations. In 1810 Great Britain signed an agreement of alliance with Portugal, which had started taking Africans as slaves to Brazil as early as 1533. The agreement included plans for the gradual abolition of the slave trade and was followed by a treaty in 1815 that better defined the path to abolition. However, as the slave trade remained one of the most important aspects of Portugal’s colonial economy, little was done to put the agreements into action.

With the independence of Brazil in 1822, Great Britain hoped for increased cooperation from the young country, particularly considering Brazil was receiving more enslaved Africans than any other country at that time. In return for international recognition of its independence, Great Britain demanded that Brazil sign an agreement similar to that which had been signed with Portugal. In 1827 a treaty was ratified promising that the import of slaves to Brazil would end within three years. During this period, the number of Africans entering Brazil grew rapidly. Fearing the (supposed) future restrictions, traders increased their business, expanding from around 25,000 sold in 1825 to 44,250 in 1829.

There was strong resistance to the proposed plan for a number of reasons. Firstly, it threatened to destroy the agricultural economy of Brazil, which heavily relied on the slave workforce. Secondly, it would put the politically influential, elite slave traders out of business. Additionally, abolition was seen as a threat to national sovereignty; it was argued that, rather than for humanitarian motives, Great Britain wanted to reduce Brazilian influence in Africa in order to extend its own empire.

However, on November 7, 1831 the definitive treaty—known as Feijó’s Law, after a priest who was instrumental in negotiations—declared that all Africans to enter Brazil from that date onward would be free. The first few years of the agreement were relatively successful: although the slave trade never stopped, only 26,095 slaves entered the country between 1831 and 1836. However, between 1836 and 1840, this number exploded to 201,140. Thus, Feijó’s Law came to be known as a law “para inglês ver”—for the English to see. Slave traders, who were some of the richest men in Brazilian society, succeeded in preventing the law from becoming practice and the number of slaves entering Brazil actually increased dramatically.

Slave traders were able to mitigate the impacts of the law because they were part of a dominant elite which controlled all aspects of Brazilian society. They had networks of suppliers in Africa, links with commercial agents in various countries, and employed many people. Furthermore, they had strong connections in courts of law and in the Chamber of Deputies, as well as support from the police and other local authorities. The 1827 treaty had given Great Britain the right to stop and detain suspected Brazilian slave ships, but under the 1831 treaty, which overruled the former agreement, suspects would be tried through the Brazilian justice system. The Brazilian justice system was full of those who benefitted from the slave trade. Under the law, slave owners were now considered kidnappers and subject to heavy financial penalties; nevertheless, with the support of those in power, impunity was almost guaranteed for infractors. Furthermore, many of the ships that might have been used for encorcing the law were deployed to quell revolts in the north and south of the country, rather than controlling the port of Rio de Janeiro (the world’s number one slave destination).

The notion of “para inglês ver,” therefore, suggested the signing of the law was purely Brazil’s measure to placate Great Britain, when really there was no intention of carrying out the promises.

What “para inglês ver” means today

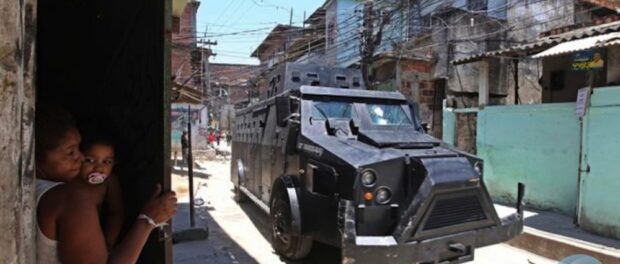

Today, a “para inglês ver” (PIV) law, policy or project is one which, from the outside, appears to address a problem, but which in practice is merely a superficial change, a temporary fix or public relations exercise intended to appease community interests and appeal to domestic and international public opinion. It does little to benefit those it purports to help, either because implementation on a well-designed policy is poorly conducted and easily corruptible, or because it is actually designed for political motives rather than social or philanthropic ones. This situation occurs when public officials lack the genuine desire or political will to institute the necessary change, and is usually accompanied by an extensive PR campaign aimed at promoting the policy. Rio’s favelas, whose origins are inextricably linked to the end of slavery in Brazil, and whose territories and citizens have historically been neglected by policy-makers, are particularly affected by these types of policies.

We can separate recent PIV projects in Rio de Janeiro into three categories. First are the very visible, expensive architectural projects which look nice but are seen as pandering to tourists rather than serving favela residents’ true needs. Second are the projects which are launched with great fanfare and wide-ranging promises, but are then only partially completed, poorly maintained, or dropped altogether. And finally, the mega-events legacy projects that generate pleasing soundbites but have little connection to reality. Here are some examples:

The PAC and Cable Car in Alemão

Complexo do Alemão‘s cable car was launched on June 8, 2011, at a cost of R$210 million (about US$70 million). The population of Alemão is around 70,000 according to the 2010 census, yet the maximum capacity of the cable car—including tourists—is 30,000 per day, which has led people to question whether it is an attraction for visitors rather than a much-needed method of transport for locals. Debates over capacity are negligible, however, as despite the reduced cost for residents (R$1), only 28% of Alemão’s residents are registered and only around 17% use the cable car on a daily basis, while 30% of users are tourists. Local activist Alan Brum argued from the beginning of proposals for the cable car that residents would not walk uphill to get to a station, that what was needed instead were other modes of alternative transport and improved road access. He also highlighted that potential tourist spending would only affect a select number of businesses around the stations, while little would reach the majority of the community in between. Most importantly, however, Alemão’s cable car was built by the PAC (Growth Acceleration Program) following an extensive public consultation process in the community, during which residents clearly delineated priorities: sewerage and sanitation were at the top of the list. Yet these have failed to materialize.

Also well known for misplaced public priorities, the PAC program in Manguinhos chose to overlook sewage which spills into the streets and instead build a state-of-the-art library and have world-renowned architect Jorge Jauregui design the elevation of the neighborhood’s train tracks, while sewage regularly spills onto the streets, visited by the Pope in 2013. And in Rocinha, where initial PAC investments favored a highly visible Niemeier-designed overpass to replace an already existing one, and a sports complex visible from the main road but which reeks of sewage, residents are fighting the City’s intended cable car project in favor of their priority: sanitation.

Providência and the “Marvelous Port”

Billed as the “second Sugarloaf Mountain” by Mayor Eduardo Paes, the city’s second favela cable car connects Providência, Rio’s Central train station, and Gamboa, covering a distance of 721 meters. A year after work had finished on the cable car in Providência, none of the gondolas had moved. Since a widely promoted launch, its timetable has been limited, only operating for a few hours in the morning and then a few in the afternoon. This means many residents have been unable to use it at all during the week. In order to build the station, the City destroyed Praça Americo Brum, the community’s primary leisure space, with the replacement space promised never built. Dozens of families were forcibly removed for the project and ultimately the City had to stop further works in the area due to the community’s legal victory over a lack of public consultation. In an interview, resident Roberto Marinho lamented the fact that favelas often receive spectacular (ly expensive) constructions, when what they really require is similar investment in more basic needs, such as sanitation. He says that if mobility were genuinely the focus of the City, the government would have implemented an elevator, like the one in Cantagalo. It is worth noting, however, that after a launch with great fanfare, the top tower of Cantagalo’s elevator, finished in 2010, has never operated. Only the lower tower is operable.

Morar Carioca

In theory, Morar Carioca was set to be the most progressive, comprehensive favela upgrading program in Rio’s history: as a primary Olympic legacy, Rio’s mayor promised all missing infrastructure services would be delivered to all of Rio’s favelas by 2020. With a budget of R$8 billion (about US$2.7 billion), the beautifully written program aimed to “integrate all favelas into the formal city” through extensive improvements in sanitation systems and transport networks, installation of drainage systems, road surfacing and street lights, and construction of green spaces, public recreational areas and social service centers. Morar Carioca was designed to build on the successes and limitations of Rio’s internationally recognized Favela-Bairro program from the 1990s, featuring greater degrees and constant consultation between the teams of architects and residents who were to be affected. After much promise and hope was generated among favela residents, organizers, and urbanists, however, the program was abandoned and its name reappropriated. Lack of investment and political will has seen the actual program slowly dismantled while its name is still widely used by City officials who have even successfully won an international award based on the virtually nonexistent program. Today, “Morar Carioca” has become a label associated with forced evictions, as the City came to use the program’s positive brand to “get away” with evictions in a number of communities.

UPP Social

UPP Social was the parallel program to the police pacification of selected favelas, to provide social and economic integration by articulating and realizing the missing public services beyond security in police-pacified favelas. It would do this through creating forums for discussion in the community, stimulating leisure and cultural activities, and providing professional training programs for youth. The program’s official website was regularly updated with reports and professional photographs from community events organized by the program, and last year UPP Social was recognized by the United Nations for being “a solid inspiration for intervention in marginalized regions of underdeveloped or developing countries.” Yet many living in pacified communities did not even know what the program was. UPP Social had promised high levels of participation from favela residents, but in most cases the residents’ suggestions or demands never came close to fruition. In one interview, a resident from Cerró-Cora summed up the program as typical “para inglês ver”: “I don’t think they’re interested in the opinion of favela residents. They ask because they have to, so they can say they asked.” The social element, so important as a complement to the policing program, never arrived, meaning the UPP is more a narrow policing policy than the comprehensive program it could have been. Such was the stigma attached to the failed program that in August 2014 the state rebranded the program as Rio+Social in an attempt to give it fresh impetus.

Eduardo Paes’ TED Talk

In his 2012 TED Talk—viewed almost 750,000 times on the TED website—Mayor Eduardo Paes lays out his “four commandments of cities,” highlighting the favela as one of the four key areas of mayoral policy in Rio. He first emphasizes the need for basic services in favelas. He shows images of a clean, modern primary school built in Colônia Juliano Moreira, and a family clinic in an unnamed favela. Although there has been investment in certain favelas, wide-ranging improvements in fundamental services have not been seen. In particular, basic sanitation is appalling (not only in favelas but especially so) and in 2013 it was estimated that at least 30% of the city did not have a formal sanitation system. In the talk Paes also states that favelas need to have infrastructure to bring them into the formal city and that they are “part of the solution.” This contrasts brutally with the dismantling of Morar Carioca and simultaneous eviction of 67,000 Rio citizens under his administration.

Institute of Public Security (ISP) statistics

In 2007 the ISP registered the highest number of autos de resistência, the term for deaths caused when suspects “resist arrest,” in Rio’s history—1,330 in just one year—confirming Rio’s Military Police force one of (if not) the most violent police forces in the world. Shortly afterwards, anthropologist Ana Paula Miranda was sacked as head of the institute and replaced by Military Police Colonel Mario Sergio Duarte. Under the governorship of Sergio Cabral, homicides dropped in Rio, making it a statistically less dangerous place. However, Miranda publicly questioned the new data under her successor’s leadership. What was hidden beneath these data, which have been given increasing prominence in the lead-up to the mega-events, was the emergence of more and more “violent deaths with unknown intention” (VDUIs) which are not registered as murders. In 2006, 1,676 were victims of VDUI, but by 2009 there were 5,647 cases, accounting for 60% of all violent deaths. The state then reevaluated some of that year’s cases, bringing the number down to 3,587; yet Cerqueira estimates some 3,165 murders in 2009 were not reported as such. Furthermore, disappearances in these years shot up disproportionately, especially in areas such as Campo Grande in the city’s extreme militia-dominated West Zone, where disappearances rose to 278 in 2013, as murder rates dropped by 60% and police officers qualified for R$9,000 in bonuses. As state politicians were publicly lauding the significant drop in homicides, in reality, Rio was as violent as it had ever been.