For the original in Portuguese with video, by Bruno Porpetta, published in Brasil de Fato and Brasil247, click here.

Architect Lucas Faulhaber and journalist Lena Azevedo have launched a book that documents the history of arbitrary evictions in the city of Rio, using statistics from the Municipal Housing Secretariat. They spoke to Brasil de Fato about their experience.

Brasil de Fato: Out of the 67,000 evictions that have taken place in Rio, the statistics show that 44.5% of them are made under allegations that residents are at risk. What kind of risk does the City cite and what do residents think?

Lucas: In the data we took from the City, the risks are not specifically cited. We believe that “risk” is not the real reason for removing families. On an unofficial level we hear of geotechnical risks as the basis for removal, but this is not specifically mentioned in the Housing Secretariat’s documents.

Another curious thing is that a large number of these “areas of risk” are in the most lucrative parts of the city or areas with potential to become lucrative. It’s a big coincidence that these areas are outlined as “areas of risk.” We are treating this as suspicious, because it is difficult to question the risk argument.

Providência is an example of this; the government said that 800 families needed to be removed there, using reports by GeoRio (the City’s geological surveying department) to prove the families were living in an area of risk. But the residents managed to speak up and hired other experts who presented a counter report saying the allegation of risk was unfounded. The counter report said it wouldn’t be necessary to remove anyone, all that was needed was hillside containment which would actually work out being cheaper than removing everyone. The difficulty of countering the risk argument is that communities don’t have the technical support to question it.

Lena: The City cited risk as an argument for eviction in Indiana, which is the lower part of Boréu, because the Maracanã stream, which runs through the community, was at risk of overflowing. But it had never overflowed, it hadn’t even gotten close to overflowing. So an expert was called in and GeoRio was forced to admit there actually was a low risk of flooding in the area.

The only reason judges did not stop the construction of the Providência cable car was because the equipment had already been bought and it would mean a huge loss if the work didn’t go ahead. Houses were removed in the area in order to build the cable car, not because of risk. In Palmeiras, Complexo do Alemão, the large amount of rain in December 2013 caused a street to collapse, taking houses down with it. But it hadn’t previously been an “area of risk;” it became one only because of poorly-made Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) works there.

PAC workers built the road, connected to the Palmeiras cable car station, on top of a spring. The road collapsed due to the rain, taking down houses with it and putting other houses at risk. The City is so disorganized that it took a few of the houses at risk due to the collapsed road and marked them off limits due to safety concerns. While some people in the area who had nothing to do with the flooding received social rent from the government, those whose houses had been marked unsafe applied to receive the same assistance but the City never found their applications; this means that someone else probably received money in their name. When the City saw it couldn’t find these residents’ applications it removed the ‘unsafe’ demarcation, but the houses really were in an area that was at risk of collapsing. I even have the documents that show the government’s change of direction. So there are areas of risk where the City does not undertake relocations and there are areas that are not at risk at all but where the City uses this argument to remove houses. This is what is happening. Removals are selective.

Brasil de Fato: Are the evictions just linked to the Olympic Games or are there other factors at play?

Lucas: The Olympics are not the real reason for removals. They serve as a justification to legitimize evictions, as well as a reason to press on with the timeline. The real motive is property speculation.

Lena: In reality, there are private interests behind this whole process of forced evictions. For example, Indiana is not connected to the mega-events infrastructure, but it is right next to a middle class condominium. So the reason for eviction is to make way for the construction of another building or to build a huge leisure space for the luxury condominium.

Brasil de Fato: Where do families go when they are removed and what are the implications of this?

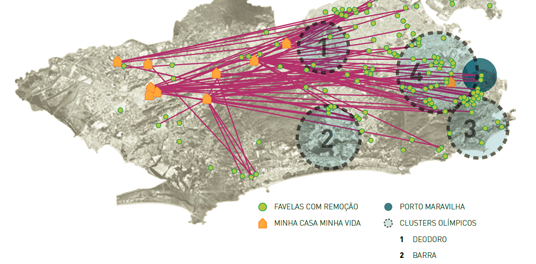

Lucas: We made a map to show where people were removed from and where they ended up, which shows families moving from one end of the city to the other. Many went to live in public housing built by the Minha Casa Minha Vida [federal housing] program, generally very far away, with a lack of infrastructure, transport, health services and all the rest. And a lot of this public housing is in areas which are controlled by militias or drug traffickers, the majority of the militias being in the West Zone of the city.

Lena: Even before people were removed to the West Zone, that region of Santa Cruz and Campo Grande already had a huge population, lack of infrastructure and schools and a precarious transport system, despite the Bus Rapid Transit line passing through there. You can see this in the large number of protests happening in the area due to the lack of public transport. There are no health centers, basic sanitation is precarious, everything is very precarious. Militias have occupied lots of apartment buildings. Some of the buildings have been taken back through the courts. But anyway, anyone who knows the militia knows how they operate. Fees, intimidation, curfews. So, as well as living in a precarious situation, residents are in the hands of criminal groups.

This is what the State is doing to evicted families. And another thing: when they are evicted to the West Zone, many of them lose their jobs because their company, or their employer (in the case of domestic workers), will say “I’m not going to pay for you to take two buses to get to work.” So many people lose their jobs or spend three hours getting to work and three hours getting home. This is what’s going on. These people are losing their quality of life in every way possible. Families are being broken up because some people prefer to move to a smaller apartment anywhere but in the West Zone, because they won’t be able to keep their jobs if they move there. So some of the family goes and the rest stay.

There are health consequences of eviction too. Take Vila Autódromo, where evictions are still going on: one of the people I interviewed died after being evicted. He was the first ever resident of Vila Autódromo and he died a week after being evicted. As well as him, five or six other elderly people died too. They died of heart attacks, strokes and very bad depression. There is no way to justify this happening: the City should be held criminally accountable for this.

Brasil de Fato: In 2016, when the City’s construction is all completed and functioning, how can the question of evictions play a part in the elections?

Lucas: I think this should be done through mobilizing people who were affected by these building works, through social movements, through the independent media, through human rights organizations. Because we have seen around 70,000 people removed from their houses and this has had very little coverage in the mainstream media.

Lena: I don’t know how anyone can say this is a perfect city. And will the government use military tanks to stop protests taking place? Because there will be protests. The UPP (Pacifying Police Unit) process is not going well. The foreign press has been much more critical than the local press in this respect. So I don’t know if this vision of the perfect city will survive. Because those who oppose the government will do all they can to show that it doesn’t exist. It’s unthinkable that the government is spending public money on creating a rainwater collection system in Vila Autódromo, when an identical system was already put in place there in 2007. What kind of Olympic legacy is this? I want to know where the Public Defender’s Office is, to question all this. Take the golf course that was built, that the International Olympic Committee said was not even necessary. The is a more critical media which has been amplified through social media, and the foreign press has been looking at what’s going on with a more critical eye too.

Brasil de Fato: Is it possible to bring evicted communities together into a united struggle? Has this been done? Where?

Lucas: This is already happening. There are various spaces which communities are using to make their voices heard. Examples include Vila Autódromo, the Committee for People affected by the Transoeste BRT Line (Comitê de Atingidos pela Transoeste) and the Popular Committee on the World Cup and Olympics (Comitê Popular da Copa e das Olimpíadas). There are other forums in which universities are present too. Of course, it is difficult to get organized because the City is working to stop people being heard. A new forum is currently being proposed that will include communities that have been removed or that are being threatened with eviction, as well as communities that are suffering from eviction in an indirect way—from a process called “remoção branca,” (white eviction) or gentrification. This gentrification is mostly happening in communities in the South Zone of Rio.

Lena: But what I noticed, in conversations with people in Vila Autódromo, is that resistance is very fragile. When the walls of people’s houses were being knocked down residents couldn’t ring anyone to call for help because they didn’t have credit on their cellphones. I think the support groups need to be in closer contact. Vila Autódromo is right in the area that the City is targeting right now. My impression is that people are not managing to get their voices heard that well, but I hope this changes, like what happened in Metrô-Mangueira. Evictions went ahead there but residents were there resisting, giving visibility to this violent process. This process did not stop when the World Cup ended; it kept on going. Some communities gained a bit of respite, but others continue to be threatened.