Twelve residents—all composing a single extended family of subsistence fishermen—occupy three small houses in Praia do Sossego. The beach lies along the coast of Niterói, the city just across the Guanabara Bay to the east of Rio de Janeiro, in the greater metropolitan region. On July 2, the families received an eviction notice issued by Judge William Douglas of the 4th Federal Circuit mandating they vacate their houses and be relocated to Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV, or ‘My House My Life’ federal housing program). As the clock struck midnight on July 15, residents of Praia do Sossego prepared to face the culmination of a threatening eviction process dating back to 1995.

Federal authorities are attempting to reclaim the beach and remove the families on environmental grounds, despite federal legislation that protects traditional coastal communities’ right to residence. The families suspect other forces are at play—namely, real estate speculation and the perception that their presence socially and visually contaminates the natural area—underneath the façade of an environmental preservation agenda.

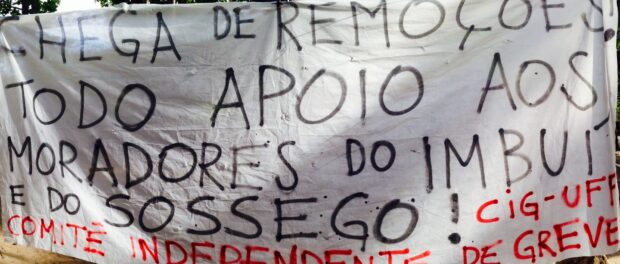

The community has been supported by a mobilization composed of activists from numerous organizations and institutions in the metropolitan region. As a result, perhaps, federal authorities have not attempted to carry out the eviction that was expected to begin on July 15. Intervening on the family’s behalf, State Deputy Flavio Serafini negotiated a deal with the City of Niterói on the afternoon of July 15 which would permit the families to relocate to the upper area of the beach. However the agreement is still pending approval from federal courts.

Cláudio, 45, whose uncles were the first residents of the community, moved to Praia do Sossego when he was seven years old. With ties to the land dating back nearly forty years, Cláudio states: “We’re already at the third generation here with my daughter [Julia, 4].” Cláudio’s wife Rosângela, 40, explains: “It’s difficult, sad, because it’s been 15 years that I’ve lived here. Everything that I know about fishing… I learned here with my husband. I stopped studying when I was 15 years old to help my mother, working in families’ houses.”

Indicating the elevated area prior to the path leading to the beach, Cláudio reminisces: “Here there was a flour oven—my father produced flour here.” Though his father was a farmer, growing up in Sossego, Cláudio learned to fish at a young age—a skill that eventually developed into his livelihood.

While Cláudio and his family have maintained a traditional lifestyle with deep ties to the sea, the socio-spatial climate of the surrounding area has dramatically changed since his youth: “It didn’t used to be valued like this: these houses [neighboring mansions] weren’t there… These houses are new, they’re around 20 years old.”

Rosângela suggests the real reason for the impending evictions is real state speculation. She said: “The [argument] of being an Environmental Protection Area (APA) is the façade of a big real estate speculation. We have knowledge, not proof, but knowledge that there’s a plan—a ready market—for a resort, guesthouse… something like that.”

Cláudio feels that those behind the eviction effort have propagated false information about their family: “We’re gaining nothing, and people go on saying things. [They say] that I have three restaurants… that I charge people to go down to the beach… Several things people say are lies. The street is public. A person has the right to come here. There’s no gate, no sign saying anything—nothing like that. It’s a piece of the city, the other [piece] is ours. They’re robbing [us], truly. The judge with this sentence is helping the City rob us again. And because of this, I’m going to resist until the end, I’m going to resist indeed. My whole life is buried in the ground here. My father died over there, my mother died over there, and I too am going to die here, even if they have to kill me—I’m only leaving here dead.”

Disputed Rights to the Land

The status of property and occupancy rights in Praia do Sossego represents a conflict between legal guarantees to land for traditional communities, private development interests, federal coastal property, and municipal environmental protection laws.

In 1991, Praia do Sossego was provisionally declared an Environmental Protection Area, and was officially monumentalized as an Area of Special Environmental Interest by municipal law in 1995. Cláudio tells the story: “After ’95 and onward was when it became valorized. So, it started to implicate us—wanting to remove us—as it’s an Environmental Protection Area. But they’re mistaken,” elaborates Cláudio, “We already lived on the site. When we arrived, it wasn’t an Environmental Protection Area.”

Rosângela explains: “We don’t have any ownership document. We have a document of the terrain. It’s not a legal deed; it’s a certificate, because they allege that it’s an Environmental Protection Area. They always used this argument, the same cause for eviction.” Despite not having a legal land deed, Cláudio cites Decree 6.040: Policy for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Peoples and Communities: “There’s a federal law—that is of caiçara, subsistence fishing—that protects us. But that’s not being used. You live by fishing, you have the right to live where you live. It protects us, but where is it? Every day that passes they’re taking us, native fishermen, from where we live to build resorts, hotels… and they don’t want to give any [working] conditions to the fisherman.”

Implemented in 2007 by President Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva, traditional peoples and communities—including subsistence fishing communities like Praia do Sossego—are legally guaranteed a right to occupy space by decree. The law defines traditional peoples and communities are those “groups culturally differentiated… that posses their own forms of social organization, that occupy and use territories and natural resources as a condition for cultural, social, religious, ancestral and economic production, using knowledge, innovations and practices generated by tradition.” The decree continues to define “traditional territories” as “the necessary spaces for cultural, social and economic production of the traditional peoples and communities, being used in permanent or temporary terms” in respect to the rights of traditional, indigenous, and quilombo communities according to constitutional guarantees.

Cláudio explains that according to a topographical analysis of the area, “42% is naval area, 44% is Environmental Protection Area, and 14% is our terrain… Our land up above is not public domain. And they want to take all of it.” Rosângela elaborates: “This topography alleges that the house up above [housing seven people, Cláudio’s nephews and their families] is not located in the area in question… [What is included] is the deck of that house up to here [the houses below]. From the deck and behind it’s the terrain.. It’s not in the area of litigation.”

For this reason, the residents find it unreasonable that the federal court insists on relocating their families to public housing since part of the private terrain falls outside the area in litigation. The compromise favorable to the families, supported by State Deputy Flávio Serafini, would permit the families to relocate to the upper area. While this agreement was approved by the City, being a coastal region, Praia do Sossego falls under federal jurisdiction and must be approved by a federal judge.

“At least having to leave from here below, we could stay to continue our lives here,” says Rosângela. “The lives of these boys is here; it’s fishing, it’s the beach. Beyond the matter of the beach, it’s their work. There are some people who say we don’t want to leave this ‘seafront life’ as if it were a whim for us. It’s obvious that the place is pretty, this tranquility, who wouldn’t want a place like this? But that’s not it, because the boys grew up here, they learned to fish… What will they do somewhere else, principally where they want to send us? That is, Minha Casa Minha Vida.”

The public housing project where the City intends to relocate the families is located in Poço do Sapê, over ten kilometers from Praia do Sossego. Rosângela continues: “It’s right here in Niterói, just that it’s a long way to go out fishing… [Here,] you wake up and go to the beach, just put on clothes and go diving to make ends meet. And [they] want to take us from here, put us somewhere far… There’s no way.”

Ten Years of Fighting Eviction

While the legal process began in 1991 with the provisional environmental protection statute, the first eviction notice came in 2004. “In 2004, we gained the right to remain but without an ownership document,” says Rosângela. “So it ended, and nobody said anything anymore… until 2011.”

“In 2011, another paper arrived, for repossession of the land once again—opening everything up again. ‘Environmental Protection Area, marina area…’ They brought [the court notice], spoke with us and we pressured them, ‘Where are we going?’ ‘Ah, you don’t have somewhere to go?’ Up to that point, they wanted to remove us without giving us the right to anything… After some time, still in 2011, [the justice official] came and brought a paper with a deadline of 30 days…. A sense of despair struck, we… remove[d] our things from here, we… rent[ed] a room up there above to be able to stay, with the fear that all of the sudden they would arrive with everything to remove our things.”

Then, a social worker from the City “came looking for us. It was a conversation like this, even ‘horizontal’ because she simply asked me: ‘Do you have somewhere to go? Do you have somewhere to store your things?’ Because when they come to comply with the order, if you don’t have somewhere to keep your things, your stuff will go to a deposit of the City, and you’ll have difficulty to get your things back afterwards.’ I was terrified, I said: ‘People, how can something like this happen?’ We remained with that concern. She came, cast all of this terror. Then after that, it calmed down. We returned home… The thirty days passed, and they didn’t come back anymore.”

“In December 2014, another court summons came with [a deadline of] one week… So, that was when everything started all over again…We [tried] to see if at least we could get some lawyer to help—at least to accompany us, to not go alone. But we weren’t able to because it was coming up very soon… So, [Claudio] said, ‘I’m going to defend us myself.’ We started to talk, separating the documents that we had—which were the certificates of the terrain, the topography, and a property tax record that one of our friends found online, paid some time ago.”

“When Claudio had the chance to speak, he presented the documents—which until then, the judge was unaware of because the documents weren’t there at the [previous] proceedings. [The judge] said it would take 45 more days to review all of the paperwork and decide. So these 45 days passed and nothing.”

In May, the decision finally arrived: “‘You’ll have to leave, the houses will be demolished.’” Another summons arrived on July 2: the families were given five days to register for Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing. The justice official told the family that “not having registered won’t impede the order” from being carried out. Ultimately, they did sign up out of fear that if they didn’t register, they would “have to leave without public housing, with nowhere to go.” The family went to the 4th Federal Circuit Court to confirm the registration as instructed, then checked to see when the apartment would be ready. The social worker said she would update the family on July 13, but they haven’t received any news. “So, that’s where we are now, waiting,” Rosângela states.

When the eviction notice arrived back in May, the family was given two months to comply with the order and vacate the houses. “This ultimate deadline ends today,” says Rosângela. According to the notice, “[City officials] would be here as of July 15. In my head, this morning they would have already been here with everything. I was preparing myself psychologically to face all of it this morning.”

With the support of the ongoing mobilization pressuring public officials, the eviction order has not been carried out thus far.

While the community has overcome these numerous obstacles in the past, they fear that this time, the stakes are higher. Having been hopeful that the land certificates, topographical map, and property tax receipt would impact the judge’s decision, Rosângela and Cláudio were outraged that the judge completely disregarded the documents.

One clause of the eviction order, issued by the federal judge, instructed the family to indicate their “areas of interest for municipal assistance in their reinsertion into the job market.” Cláudio rebuts: “But I’m already working. I’m not unemployed!” Pointing towards the ocean, he continues: “My work is over there. How’s he going to reinsert me into the job market, if I’m already working?”

“My House, My Life is Here”

The family feels an unwavering connection to their home, Praia do Sossego. Rosângela describes that it’s difficult to see Cláudio—“who at times seems sort of tough”—threatened with the loss of his home. “His life is here. Julia is growing up, she’s going to be 5 years old, and she too is very attached to this place… On days that she doesn’t go to the beach and doesn’t swim, she gets sad, impatient: ‘I want to go to the ocean, I want to go to the ocean.’… It’s painful… We’re all very sad.”

Cláudio echoes the somber sentiment: “I’ve never been hungry, but I’ve been through difficulties. I’ve caught many fish—I’ve sold half the fish in order to buy oil to fry the other half. These days, I’m rich because I open my fridge and I find things to eat, thank God. But my life was a struggle—and to this day it is a little bit—but today I sustain myself… And if someone takes me away from here, takes me who knows where, my life won’t be easy. We will try to overcome, we’ll try, but it’s going to be very difficult.”

Cláudio continues: “It’s going to affect the life of everyone. [The judge] says he’s going to give me “My House My Life.” But my house, my life, is here.”

Click here to show your support to the families to remain in upper Praia de Sossego.