Rio de Janeiro is branding itself as the city of the future. You only have to visit the Port Region of the city, currently undergoing huge urban transformation as part of the “Marvelous Port” project and its nearly ready Museum of Tomorrow to see this.

Those wanting to get to know this rapidly changing area of Rio must not neglect its past, however. Rio’s Port is deeply connected to the African and Afro-Brazilian history of the city, and Brazil as a whole. Approximately five million of the 10 million African slaves shipped to the Americas were brought to Brazil, and Rio de Janeiro was the main point of arrival, making it the largest slave port in world history. In the early 19th century half of the city’s population was enslaved.

The recently launched educational website Afro-Rio Walking Tour aims to do just that. Created by North American historian and long-term Rio resident Sadakne Baroudi, the website offers information about and advice on how to visit key sites in the history of slavery in Rio’s Port, in English, Portuguese and French.

One of the themes that comes out strongly on the Afro-Rio Walking Tour is that Rio’s history of slavery has often been concealed, as is common in cities and countries with a legacy of slavery.

In fact, several of the most important sites in the history of slavery in Rio, listed on the Walking Tour website, were only “rediscovered” in recent years. And many struggle to get recognition or funding.

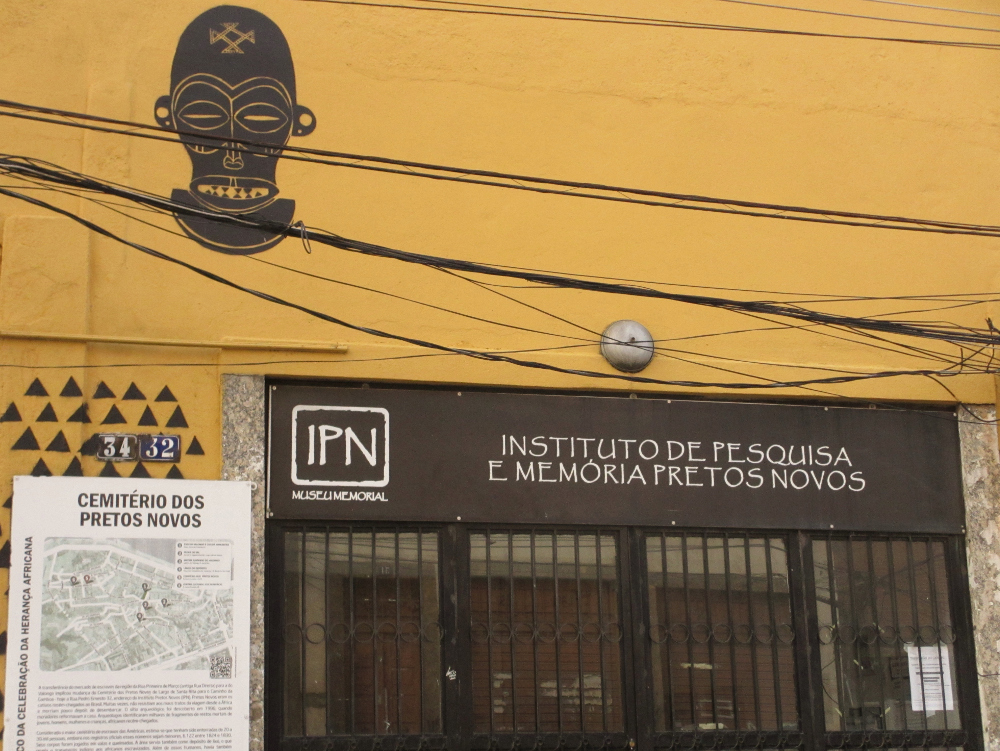

The Cemetery of the New Blacks (Cemitério dos Pretos Novos) is one example. The cemetery was the burial site (perhaps it is more accurate to call it a dumping ground) for thousands of Africans who died on the journey to, or soon after arriving in Rio, prior to sale, between 1769 and 1830, when it was closed. Its location remained forgotten until 1996, when a couple renovating their house discovered they were living on top of it.

A major archaeological study took place and the couple, Merced and Petruccio Guimarães, took it upon themselves to create a research institute and memorial center in 2005, which they continue to run themselves, with precariously low levels of funding.

The fact that the cemetery lay forgotten for so long, and the struggle the Guimarãeses have had to keep the memory of the buried slaves and Rio’s black heritage alive through their own efforts, contrasts with the high-profile building works through a massive Public-Private Partnership underway on the same street. Their street is currently being dug up for the VLT light rail system: a 28 kilometer network which the City aims to have completed in time for the 2016 Olympics.

Another recently “rediscovered” site in the Port Zone, also detailed on the Walking Tour website, is the Valongo slave market. Slaves were brought to Rio on squalid ships and sold here. The Valongo was renamed and covered over in 1843 for the arrival of future Emperor Dom Pedro II’s Italian bride and became known as The Empress’ Wharf (Cais da Imperetriz). After being filled in and paved over in 1911, the original Valongo remained ignored until 2011 when it was uncovered and excavated during building works for the Marvelous Port redevelopment project.

After a hard-fought battle to preserve the Valongo, one can now visit the site and see the three layers of city streets on display.

The website also introduces notable black Brazilians in the history of the city, such as the engineer, inventor and abolitionist André Rebouças. Right next to and standing over the Valongo is a beautiful red-brick warehouse, built by Rebouças in 1870. He is known for modernizing ports across Brazil and for designing a modern sanitation system for the city, putting an end to the practice of using slaves to transport Rio’s sewage by hand.

The site also features information on Pedra do Sal and the area known as Little Africa, where Rio’s famous samba and carnival traditions originated. It also provides information on the traditional Afro-Brazilian religions which flourished in the region.

Beyond the Port Zone, the website also pinpoints places to visit next door in downtown Rio, including a pair of buildings around the corner from Largo da Carioca: the Black Church and the Black Museum. Torched in 1967, the buildings are sparsely decorated and in poor condition. The museum is a useful stopping-point on a journey around Afro-Rio, especially for the way its small collection, managed by one dedicated curator, shows the difference between the reality of slavery in the city and the sanitized image of slavery, promoted in paintings from the time, that still persists in the nation’s memory today. As the Walking Tour mentions, the entrance to the Black Museum is confusingly difficult to find.

The Walking Tour website—an in-progress, expanding project—details a wide range of important places, people and stories to help visitors “learn the African history lived on the streets of Rio de Janeiro.” The website is an accessible starting point for Rio residents and visitors who are curious about the history of a city which is speeding ahead with redevelopments in time for the 2016 Olympics.

Click here to visit the website.