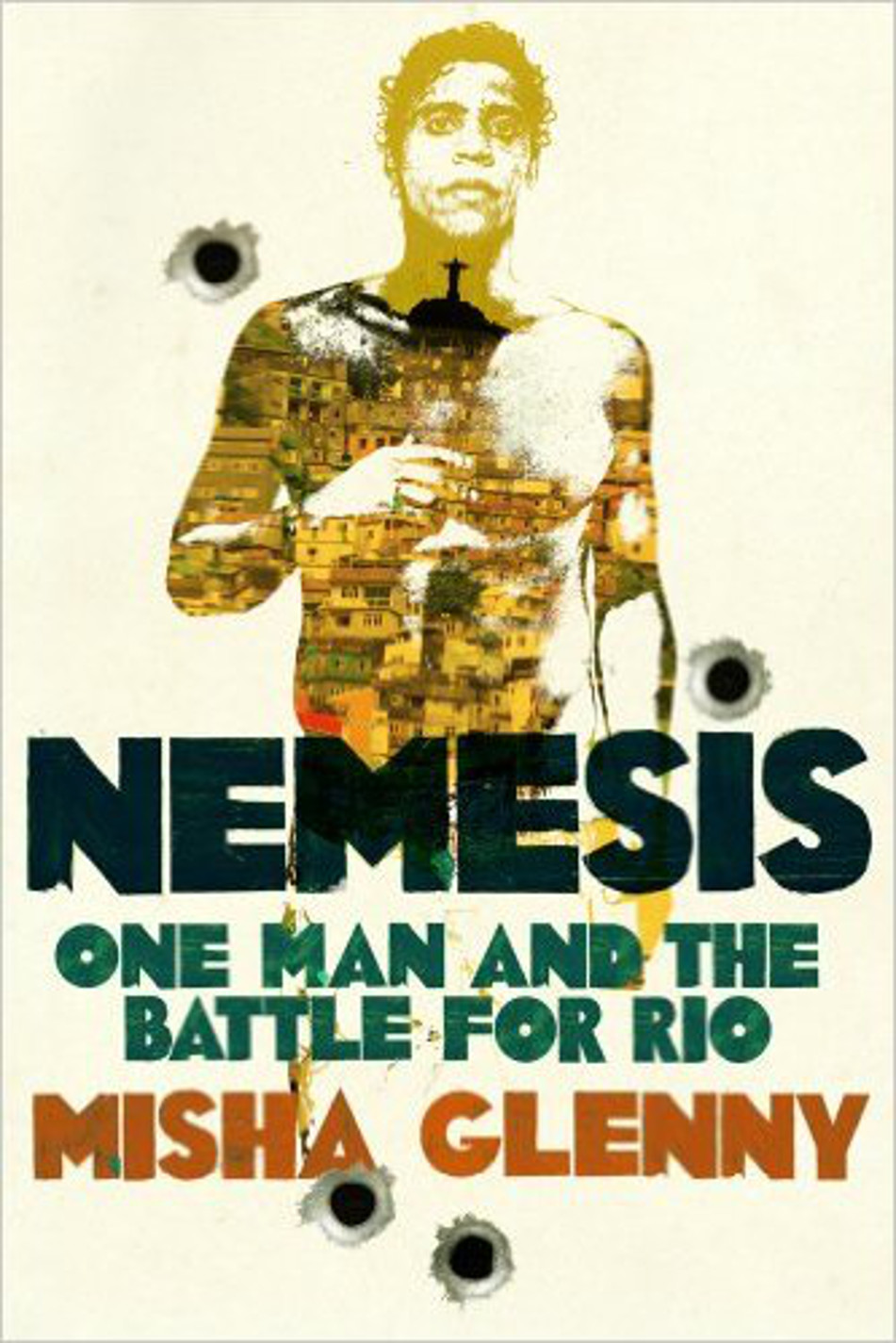

At the beginning of Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio, journalist Misha Glenny recalls a tour he took of Rocinha, Rio’s largest single favela, in 2007. During the tour, his guide referred to Nem, the don of Rocinha, as “the man who keeps the peace here.” Four years later in the run-up to the pacification of the favela in November 2011, Nem was dramatically arrested amid flashing cameras in Rio’s South Zone. For the politicians responsible for creating the ambitious Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program in the city’s favelas, the arrest was a flashy success story.

Misha Glenny’s latest book charts the incredible story of Nem, born Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes, from his early life to his entry into the drug trafficking business aged 24 and his four years as kingpin: a long reign, given that “the average life expectancy of the Rocinha dons, once they reached the top, was approximately ten months.” Nem’s rise paralleled the explosion of the cocaine trade in Rio in recent decades.

Glenny spent 28 hours with Nem at his high-security prison in Campo Grande in Rio’s West Zone and this series of interviews form the basis for Nemesis. The book is also the result of interviews with a wide range of individuals: Nem’s family, friends and enemies, Rocinha residents and public figures, as well as police, politicians, journalists and lawyers.

This range allows Glenny to show Nem’s story within a wider context: the creation and history of Rio’s favelas. These communities remained largely neglected by the State for decades and especially during the cocaine boom when “Brazil became established as the transit country of choice to feed Europe’s rapidly growing cocaine habit.” The drug trade in Rocinha is responsible for approximately 60% of all cocaine consumed in Rio too.

The absence of the State combined with the violent rise of the drug business in Rocinha from the 1970s onwards allowed dons like Nem to operate what sometimes seems like a state within a state.

Glenny cleverly reflects on the conflict that stems from a situation where drug traffickers use violence to hold territory while distributing some of their profits within the community: “Throughout my conversations with Nem, my strong and abiding impression was that he passionately wanted to do good but that this was impossible to reconcile with being in charge of a large group of armed men and a criminal organization boasting a huge turnover.”

Glenny quotes Nem talking about the first “Don of the Hill,” Dênis, in a similar way. “The drugs business occupied the vacuum left by the state,” he said, “otherwise this would have been a lawless territory.”

Crime statistics cited later in the book somewhat corroborate this. Nem’s arrest (a mystery which Glenny picks at from many different angles) happened at the beginning of the pacification process of Rocinha. Glenny shows a nuanced view of the effect of the UPP installation in Rocinha. “The reduction in the number of armed members of drug gangs on the streets meant that homicides in the pacified favelas were down by as much as 75%,” he notes. “But it also meant that the policing function of the gangs ceased too. As a consequence, domestic violence had increased four-fold, while rape was three times more common and burglary twice as likely.”

“Throughout my conversations with Nem, my strong and abiding impression was that he passionately wanted to do good but that this was impossible to reconcile with being in charge of a large group of armed men and a criminal organization boasting a huge turnover.”

Glenny’s book touches on one of the key rupture points of the UPP program–the murder and disappearance of Amarildo de Souza at the hands of UPP police in Rocinha–and the perceived failure of the second, social phase of the UPP program.

Glenny’s book is by no means a rose-tinted view of drug traffickers like Nem. On several occasions the author highlights the macho and misogynistic culture of drug traffickers, a culture in which violence against women is common. Nemesis shows the violence and precariousness of the drug business in Rio’s favelas, mapping out the different criminal factions vying for power across the city. In this context, it is hard to believe Glenny’s description of Nem’s childhood as violence-free, before the boom in cocaine.

The book also provides interesting insight into how favelas are perceived by non-residents, inside and outside Brazil, hinting that this has an impact on their stigmatization. Glenny’s description of the media frenzy surrounding Nem’s arrest might lead some to make parallels with the famous scenes captured by a similar media swarm in 2000 during a hostage-taking on a bus in Rio’s South Zone. The event was examined by José Padilha in the 2002 documentary Ônibus 174 (Bus 174).

Both Glenny’s book and Padilha’s documentary fulfill an important function, using the two unrelated events to examine the wider tangle of circumstances and context behind the actions of individuals involved in crime in Rio.

This, as well as Nem’s unusual life story, is what makes Nemesis such a fascinating read.