This is the third article in a series by guest researcher Jeffrey Omari,* on ICTs in Rio’s favelas.

During the last year in Rio, I’ve formed a routine of visiting Ipanema beach on Sunday afternoons. Working nearby at the feira hippie handicraft market, which happens every Sunday, makes spending time at the beach each week easy and convenient. On Sunday September 20, I left the fair and headed to the beach as I normally do. I arrived at Posto 9 (the 9th in a sequence of beachside posts indicating one’s location in the heart of Ipanema) and began my usual walk towards Arpoador Rock near Posto 7. By the time I arrived at Posto 8, just short of Arpoador, I could sense that something was different. Since I visit this beach at the same time every week, I had grown accustomed to the casual carioca ocean front vibes, even when the beach is crowded. This particular week, however, the demeanor of the vast multitude of people congregated on both the beach and the adjacent Avenida Vieira Souto suggested that something had run amok.

I was by myself that Sunday and decided I would go home and return to the beach another day, when the crowd was less intense. The metro train I boarded at General Osório square for Centro was jam-packed, which is somewhat unusual for a Sunday evening. I’ve ridden plenty of crowded trains in Rio but, like on the beach, the energy of the crowd on this train was particularly raucous. I was merely headed home, but it felt like I was going to a football game at Maracanã. Despite the uproar on the train, I didn’t observe anyone being disrespectful. It just appeared to be mostly children and teenagers headed home from a day at the beach releasing youthful energy, like kids and teenagers do.

I realized the next day, however, that the disorderly scenes I had witnessed both on the beach and the metro offered a hint of the chaos that had unfolded that Sunday in the beachside communities of Arpoador, Copacabana, and Ipanema. The madness on the beach was the result of arrastões, a term that translates literally to trawler fishing nets but which is used to refer to the mass robberies that historically occur on Rio’s beaches, generally in summer months. On weekends when the weather is hot, the beaches in the South Zone draw large crowds from across the city, including groups of teenagers, mostly Afro-Brazilian, from the North Zone who want to play and cool off by the ocean. Some of the more unscrupulous teenagers, a small minority of those who venture to the beaches on such days, engage in arrastões.

While some South Zone residents have reacted by using Facebook and Whatsapp to mobilize justiceiros—a strategy in which groups of vigilantes attempt to take the law into their own hands and “do justice” to quell the arrastões—the City has responded by profiling innocent black youth and eliminating certain bus routes from the North Zone to the South Zone to make it more difficult for North Zone residents to visit the beaches. These measures come on the heels of the Brazilian Congress approving a controversial law that, pending approval by the senate, would lower the age of criminal responsibility. The collective force of these initiatives has left many with the feeling that underprivileged youth in Rio, who have historically been stigmatized in the mainstream media, are under a new, more spirited attack as the Olympics draw near. According to Complexo da Maré resident Walmyr Junior, “choosing to stigmatize favela youth as criminals reaffirms the position of the white, heteronormative middle class in Rio’s South Zone for the cutting of ties between the North and South Zones, which reveals the existence of a carioca apartheid.” As a North Zone resident, Walmyr Junior describes the visceral experiences of the social and economic divides that exist in relation to his community’s South Zone counterparts.

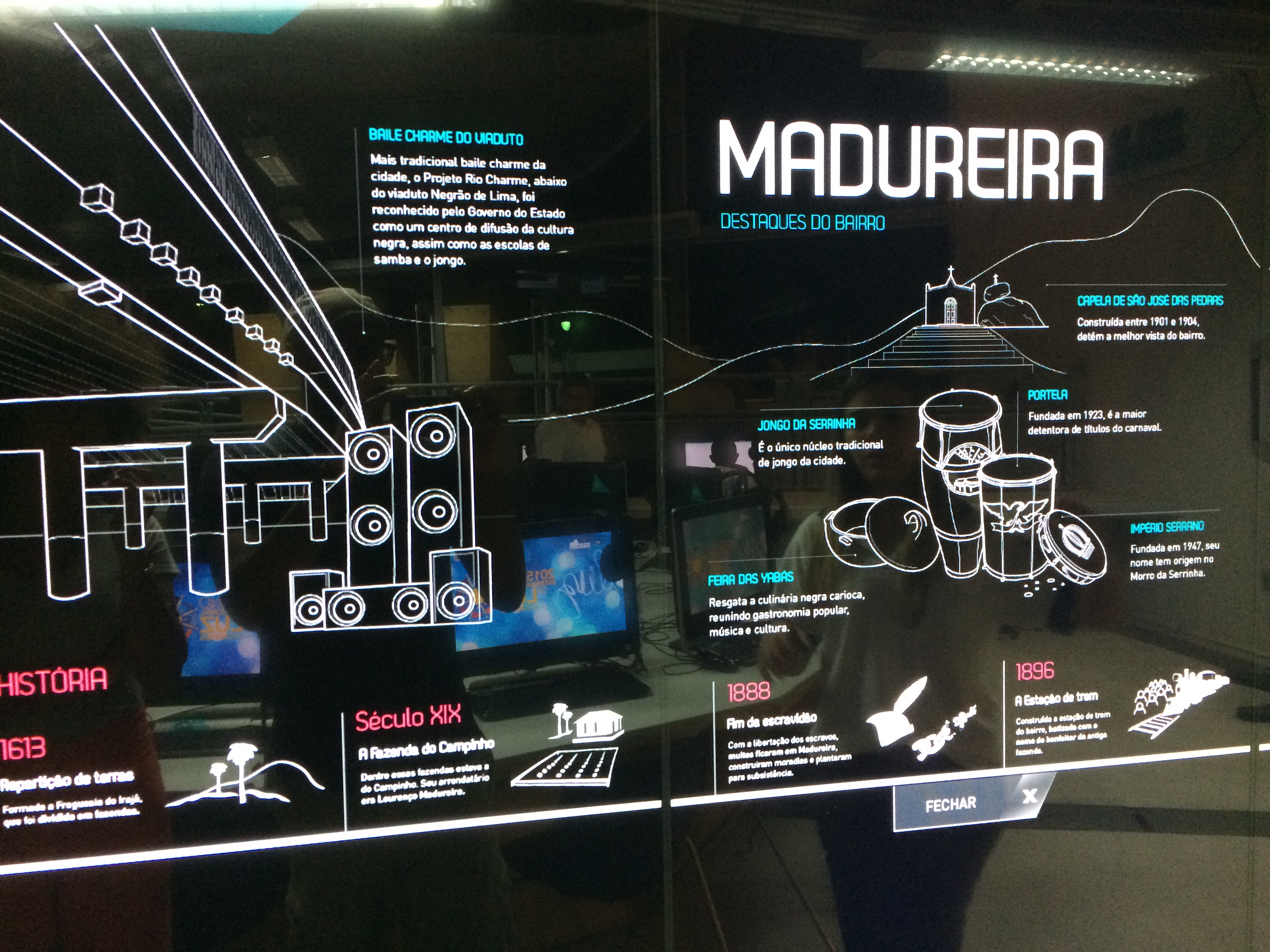

The week following the incidents on the beach, I visited the Knowledge Ships, or Naves do Conhecimento, in Madureira and Triagem. These centers, and each of the other five Knowledge Ships (located in Padre Miguel, Irajá, Penha, Santa Cruz, and Vila Aliança), are located in the North and West Zones, which are geographically remote and dramatically different in terms of scenery from South Zone. What is painfully obvious about the communities targeted for Knowledge Ships is that they are subject to both the City’s digital inclusion and social exclusion policies. While embracing the benefits of their newfound, City-sponsored technological access, it is the residents of these same communities that are simultaneously fighting City-sponsored segregation.

On visiting the Knowledge Ships, what initially struck me were the vast economic and human resources invested in these centers that aim to promote both digital and social inclusion. According to Rio’s Secretary of Science and Technology, Franklin Dias Coelho, the “mission of the Knowledge Ships is to overcome these [social and technological] differences and integrate the city.”

While Rio’s Knowledge Ships offer digital education classes and instruction through interactive computers, digital inclusion efforts such as these still appear to focus primarily on the physical availability of hardware and the computers that facilitate Internet access. The stark contrast between the City’s investment in technology in favelas and its recent efforts to prevent the digitally included residents of the North Zone from visiting public spaces in the South Zone imply that the City views technological and socio-geographic divides as separate issues. However, the threads of technological inclusion and social exclusion are inherently interlaced.

Mobilized by activist groups like Coletivo Papo Reto, residents of favelas and other North Zone communities have their own ideas for what constitutes real integration. They have made use of their digital inclusion to organize peaceful protests, via Facebook and social media, to assert their rights to the South Zone spaces where they face exclusion.

In addition to providing the technological access necessary to bridge the digital divide, the City must consider how technology could be harnessed to promote a broader process towards social inclusion and urban integration. Full access to the world through the Internet is not enough when physical access to the city is still restricted.

*A PhD candidate from the University of California, Santa Cruz, Jeffrey Omari studies Internet access and cyber law in Rio de Janeiro.