On Tuesday, March 8, Mayor Eduardo Paes finally released his plan for the community of Vila Autódromo, adjacent to the Olympic Park. The absence of a public City plan until that point had kept residents in a sustained state of stress, skeptical of the mayor’s promises that those who wanted to stay could remain. Unfortunately, the City’s plan does not offer full relief. Designed and delivered in a top-down exclusive process, the City’s plan calls for the near-total erasure of existing structures, ignores the needs identified by residents, and seeks to hide the experience of forced removals. It is a case study in poor quality urban planning, its failings all the more stark when compared to the People’s Plan developed by residents and supporters.

The mayor presented the City’s plan to a select group of journalists at a press conference in Cidade Nova in central Rio. The time and location of the press conference were changed just hours beforehand so community members could not attend the event and speak to the press there, though they held their own press conference at the original location in Botafogo. A group of residents and supporters went to City Hall this week, on March 15, to demand the mayor present the plan to them directly, so that they can begin to discuss its proposals and formulate a response.

Maria da Penha, whose home was demolished last Tuesday on International Women’s Day, explained: “Our idea is to underscore that he hasn’t called us to show us the plan. We’ve seen it, but officially with them, we haven’t. Because we want to discuss it with them. We want them to receive us to discuss things.”

Contrasting plans: The proposals

The City’s plan states there are 25 remaining families in Vila Autódromo and proposes to build 30 houses. The latest version of the People’s Plan, publicly presented on February 27, calls for 50 houses.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the mayor’s presentation is the proposal to completely demolish the existing house structures in order to build a single street of uniform small attached houses. In the Powerpoint, so far the only publicly available account of the plan, there is no explanation for the process or timeline for this demolition and reconstruction. Note that the full demolition reflects what urban planners refer to as urban renewal, very different from the promised on-site upgrading.

Given the City’s previous tactics of deception and intimidation coupled with the lack of transparency, resident Delmo Oliveira insists that community members won’t leave in order to implement the mayor’s plan: “We don’t believe him. Only when we see it will we believe him. When it’s ready. If he makes us leave our homes to build, we won’t leave. He’ll demolish them and then go to the courts to make [full removal] legal.”

During the invite-only presentation itself, Paes affirmed the new houses would be built before the Olympics, and that most of the remaining residents can stay in their current homes while the new houses are being built.

In comparison, the most recent iteration of the People’s Plan shows the feasibility of maintaining existing structures and spaces, including homes, the Catholic church, the now-demolished Neighborhood Association building, and the community-built ‘Parquinho’ playground. It also calls for new homes for the residents who never accepted deals from the City but whose homes were demolished anyway.

The City plans to provide demanded public services from sewerage and lighting to repaired roads. The plan also provides for a church and a basketball court, but noticeably lacks plans for the majority of the spaces proposed by residents to address specific community needs, including a day care, a multi-use space with activities ranging from adult education courses to an employment agency, and exercise spaces for the elderly in addition to other leisure spaces. The City’s map lacks a Neighborhood Association building, despite the fact that the Association is integral to Vila Autódromo’s history and sense of community, and all favelas are expected to have one to legally represent them.

The People’s Plan explains the importance of these public places: “The community has been characterized, throughout its whole history, by solidarity and cooperation between residents, which represents a large and important accumulation of experiences of mobilization, organization, and mutual support.” By overlooking important shared spaces, the City’s proposal would alter the social nature and structure of the community.

Residents’ proposals for better access to the rest of the city, including the return of a recently cut bus line, go unaddressed by the City’s plan thus far. Two schools proposed by the City respond to some of the residents’ concerns for better access to education, but residents had suggested a school be built in the Olympic Park, not on Vila Autódromo land itself.

Delmo Oliveira questioned the real motivation for the two schools for just 30 families: “They have two stadiums that are to be taken down after the Olympics. [Paes] already said they would become schools. Why does he want to put them on both sides of Vila Autódromo? To hide the fact that there is a community there? Why these two schools?”

The mayor’s presentation also lacks designated space for local businesses. Vila Autódromo had a number of thriving businesses including a grocery store, bakery, and small restaurants run by local entrepreneurs. Delmo also commented on this shortcoming in the mayor’s presentation: “For example, the commercial center? Where are the people of Vila Autódromo going to buy bread?”

Perhaps the most symbolic (and unsurprising) omission from the City’s plan is the residents’ proposal to maintain the ruins of one demolished home as a “space of memory and truth, evidence of the process of demolitions and human rights violations.” By proposing to build a new neighborhood from scratch, the City is not just rejecting the idea of one dedicated memorial, but attempting to erase all physical evidence of the community’s struggle.

Contrasting plans: The stories they tell

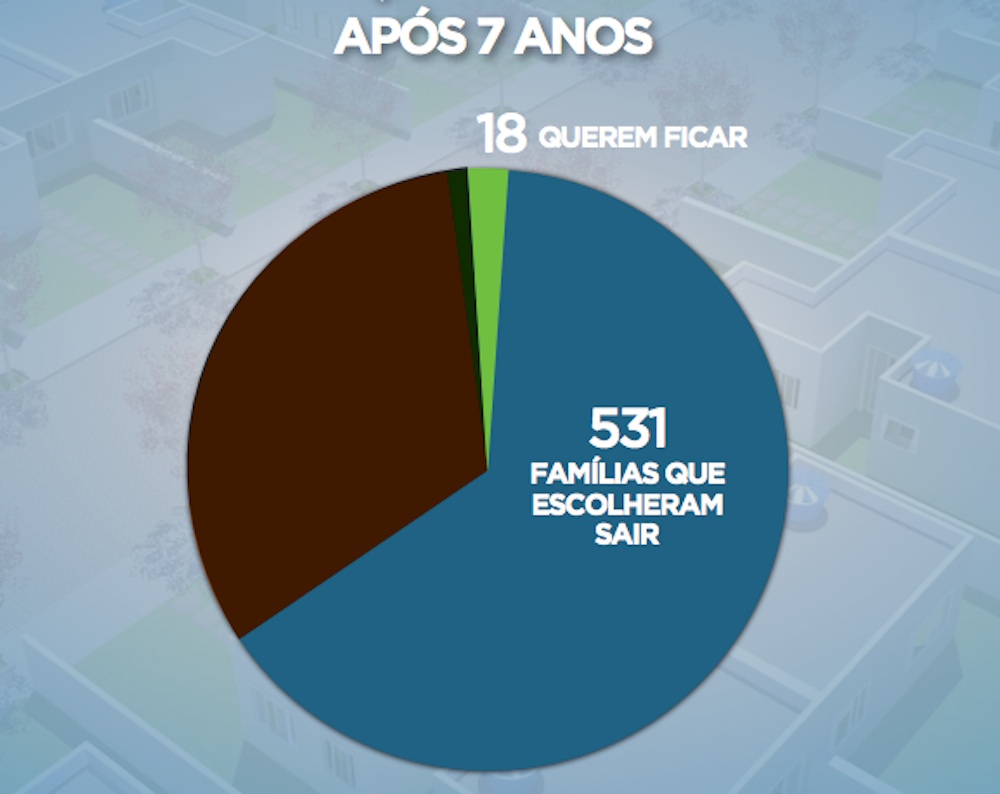

The history of community struggle is already absent from the mayor’s Powerpoint presentation of the urban renewal plan. A series of pie charts tell a story in which one-third of the community had to leave, while 97% of those who did not have to leave “asked to” and “chose to” leave.

Meanwhile, the marketing-friendly photo of public housing to which residents have been removed features smiling children having fun in a pool. This is a one-sided portrayal of housing that has suffered from structural problems and where some residents struggle to meet costs. The public housing’s pool is currently overtaken by fungal growth and residents have been prohibited entry for months, told they must pay for maintenance themselves. Delmo expressed skepticism towards the mayor’s implications: “[Paes] says there are 500 happy families in Parque Carioca, but I challenge any reporter to find those 500 families.”

The People’s Plan, in contrast, documents the City’s extensive efforts to convince people to leave:

“The threats included saying that the last [families left] would get smaller and worse apartments and that, by September 2014, none of the community would be left.”

“Official information never arrived, maintaining a climate of fear about what would happen with those who didn’t negotiate [to leave the community].”

The community plan describes the gradual decline in quality of life in the neighborhood as homes were demolished, the water supply was disrupted by Olympic Park construction, services like garbage collection and electricity were reduced, and trees were removed.

It documented, in May 2014, that 187 families wanted to stay. Subtracting the 25-50 families who remain, this means some 137-162 families negotiated to leave only after May 2014, whether due to intensified pressure, the deteriorating neighborhood, higher incentives, the declaration of eminent domain in March 2015, or other circumstances. The mayor’s plan takes pains to show that not everyone wanted to stay, which is true, but it deliberately obscures the well-documented fact that most people who negotiated did not initially, or even ultimately, want to leave.

The mayor’s presentation also tells a simple story of why people had to be removed: either their homes were in the way of an Olympic Park access road, or they lived on the marginal stretch of land along the lagoon, which supposedly needed to be recuperated for environmental conservation. Since 2009, however, the official reasons for evictions in Vila Autódromo have changed numerous times. A map in the People’s Plan highlights four other motivations residents were told caused or justified removals: to make way for water pipes, to widen a bordering road, to “liberate” the front of a 5-star hotel and construct a pedestrian bridge, and finally, instead of the environmental justification, to “liberate the view of the residential buildings built after the Olympics.”

Contrasting plans: Process and transparency

The discrepancies in content, depth, and format between the two plans is a reflection of the very different processes that took place to develop them. How the City arrived at the plan the mayor proposed last week is not public information. RioReal Blog reports Paes claims he couldn’t release the plan earlier because “he needed to know how many residents would stay and that he had to keep it secret to avoid new arrivals in the Vila, looking for a chance to live in a just-upgraded neighborhood.” Surely, the City could have found a way to distinguish long-term residents from new arrivals. But it’s true that releasing a plan earlier could have impacted the number of residents—perhaps fewer would have left out of fear and sustained stress.

The mayor’s sparse 24-slide Powerpoint presentation is a product someone could have put together in about thirty minutes, since the proposed map isn’t tailored to the existing physical neighborhood or to residents’ demands. The image of the projected row of houses could be a design for anywhere.

The City plan’s process alone (not taking into account the full removal process) fails at least three of the eight Principles on “Overall Responsibility to the Public” outlined by the American Institute of Certified Planners: provision of timely information; participation; and conservation of the built environment’s heritage. It fails all seven guidelines for building great communities proposed by the Project for Public Spaces, which stress community engagement and encouraging communities to articulate their visions.

In contrast, the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan has evolved publicly and transparently since 2011, as the plan itself describes. The residents’ problems, proposed solutions, and vision for the neighborhood were debated and articulated over the last five years in community meetings, led by residents and supported by urban planners of two universities, all explicitly acknowledged at the end of the document. Different iterations of the plan have taken into account the City’s actions in and around the community, showing Vila Autódromo’s adaptability and willingness to work with the Olympics and the City. It is not just a plan for physical upgrades, but a plan for “urban, economic, social and cultural development.”

By producing a collaborative community plan, Vila Autódromo residents demonstrate the type of planning process they believe in. “We’re showing what kind of city we want, to which we have the right, and how to construct it,” the plan explains. In this envisioned city, “it’s the community of Vila Autódromo that decides and establishes the priorities…the population that lives the day-to-day reality and difficulties who will say what is necessary and how it should be done.” The People’s Plan’s authors see the plan as a model for the rest of the city, for “a new form of building a democratic city and a new form of planning the city.” All of this, they argue, is the people’s right: “our right to decide our destinies.”

Contesting the struggle in the media

Though it had garnered some national and international media attention in previous months, Vila Autódromo’s struggle has been extensively covered the last few weeks due to the recent demolitions of the Neighborhood Association building, Heloisa Helena’s house and religious site, and Maria da Penha’s home on International Women’s Day.

Paes has maintained in media interviews that the City has been in constant dialogue with the community over the years, especially in the case of the demolition of Penha’s home. However he has recently tried to portray the remaining community members as hold-outs who are only seeking money, stating that “in most of the cases in which residents want to stay there, it’s because we didn’t reach a price. They want to receive a very high price for their homes.”

The mayor is also attempting to gain media favor by offering transparency in the cases of those who have already left, painting former residents as greedy estate owners: “Those who had more than ten homes, who turned Vila Autódromo into an estate, using the poorer residents, everyone will know them. Everyone will know how many apartments and how much money they received in compensation. We are not going to allow those who left Vila Autódromo with advantageous negotiations to use this opportunity to make themselves look like victims.”

Not to be distracted, residents of Vila Autódromo have kept the pressure on Paes, mobilizing the #UrbanizaJá social media video campaign to demand promised on-site upgrades. Activists, academics, politicians, celebrities, and members of international organizations and solidarity movements have joined the campaign. Several participants have pointed out the original People’s Plan would have only cost R$13.5 million, as opposed to the more than R$208 million the City has spent removing the community. Though the mayor has now presented the City’s plan, this week Vila Autódromo resident Sandra Maria urged supporters to continue the campaign: “That’s why we need this #UrbanizaJá campaign to continue. Because the big question of the campaign is when. When, Mr. Mayor, will Vila Autodromó receive upgrades? This question hasn’t been answered.”

The mayor should also explain why his plan insists on erasing the current neighborhood and its memories, and why he won’t simply accept the internationally awarded People’s Plan.