On April 21, a 50-meter stretch of the seaside Tim Maia bike path collapsed under a strong wave near the São Conrado neighborhood in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, killing at least two. Victims included 60 year-old Rocinha resident and street-sweeper, Ronaldo Severino da Silva, and 54 year-old engineer, Eduardo Marinho de Albuquerque, with another individual still missing.

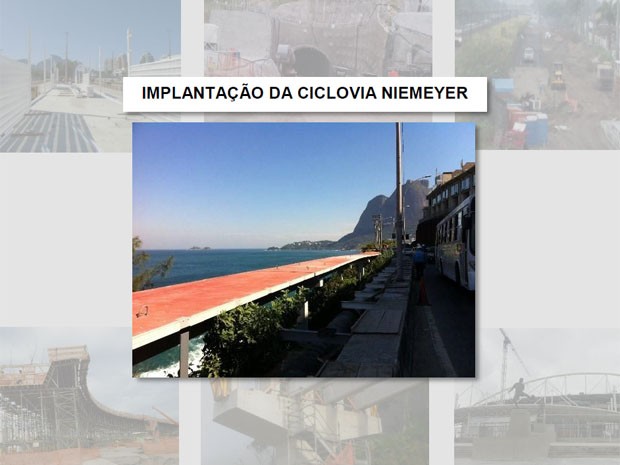

Designed to be part of the Olympic “legacy,” the bike path was launched just over three months ago. It collapsed two hours after the Olympic torch was lit in Greece and set off on its five-week journey towards Rio for the 2016 Olympics opening ceremony on August 5. The construction of the almost four kilometer long bike path (intended to be about seven kilometers once complete) cost around R$44.7 million, R$8.9 million more than initially programmed.

Corruption

The collapse occurred during an especially difficult moment in Brazilian politics, in the context of calls for the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, and also of investigations for Operation Car Wash around connections between semi-public oil company, Petrobras, and construction companies, with allegations that Petrobras executives accepted bribes from construction companies in exchange for contracts at inflated prices.

The companies behind the construction of the bike path, Contemat and Concrejato, are part of consortium Concremat, which is already being investigated by the Federal Police in a related embezzlement scandal called Operation Dry Lives. Concremat and other construction companies that worked on the rerouting of the San Francisco river, by means of construction of new canals, are accused of also “rerouting” approximately R$200 million.

Additionally, Concremat has indirect ties to other companies involved in the Operation Car Wash scandal. Concremat’s Executive President, Clóvis Renato Peixoto Primo, is a former employee of Andrade Gutierrez, which is a part of the Angramon consortium, a focus of the investigations. In Rio de Janeiro state, of the three companies leading in public contracts–Odebrecht, OAS, and Andrade Gutierrez–two are cited in the investigations. These companies, and creative subcontracting and partnerships, have been referred to as cartels by some.

Under Mayor Eduardo Paes’ administration, the relationship with Concremat has become closer: the City Government signed 16 contracts with Concremat from 2000 to 2008, but under Eduardo Paes’s administration beginning in 2009, that number jumped to 54, with a total value of R$451.6 million. Questions are being raised around this increase, particularly in light of Concremat being run by members of the family of Rio de Janeiro state’s Secretary of Tourism, Antônio Pedro Viegas Figueira de Melo. Figueira de Melo denies connections with his grandfather’s business’ operations.

Construction

All specialists who have reviewed the bike path plan, including engineer Antônio Eulário Pedrosa of the Regional Council of Engineering, Architecture and Agronomy (Crea-RJ), stated that it did not take into account the ocean and its waves. Professor in coastal engineering at Rio’s Federal University (Coppe/UFRJ), Paulo Rosman, said the sea was particularly aggressive that day, but agrees that the planning did not take stronger waves into consideration.

In a recent news report, Ana Teresa Nadruz, an architect and urbanist with 40 years experience, highlighted: “The error began in the project’s conception, with the construction method of a fragile pre-cast structure in a place subject to rip currents… Its breakup was a tragedy foretold.”

Following the above reports, architect and urbanist Eduardo Nei de Jesus Vieira and civil engineer Manoela Silva highlighted the “determining factor for the collapse was the fact the [cycle] track was only supported by the pillars, without any sort of anchoring.”

In April last year the Municipal Secretariat of Public Works released a report containing updates on the bike path’s construction. The report showed:

- The planning did not consider ocean waves and currents.

- Several of the constructed points were considered “tidal splash zones,” especially the area along the coast.

- The only risks considered were in relation to the heavy traffic of vehicles passing by and night work on the slopes and signaling.

According to Concremat, “they followed all the protocols and security norms” and “the materials used and the quality of construction followed all the technical requirements established in Brazilian standards.”

The mayor has said that the causes of the accident can only be determined after the completion of two audits. The National Institute of Waterways Research (INPH) and the Alberto Luiz Coimbra Institute of Graduate Studies and Research in Engineering at Rio’s Federal University (Coppe/UFRJ) have been commissioned to carry out these investigations. Paes assured the press: “We have hired auditors, Coppe and INPH, to identify the technicalities and responsibilities of those who were responsible. [They will] see if there was a design error, runtime error, tracking error, in the construction. What we can say at the moment is it is clear, without even investigating, that things weren’t done accordingly.”

Olympic Legacy

The Guardian writes of the tragedy that it deals “another blow to the city’s credibility as an Olympic host.” Indeed, days after the collapse, social media celebrated #100DaysToGo until the Games’ opening ceremonies. The collapse adds to the shadows of the political and corruption crisis, and concerns around Zika and water pollution.

Critics of the City’s preparations for the Olympics see the collapse of the bike path as yet another example of how preparations have been rushed, operating in a state of exception justified by the mega-event, and subverting traditional processes. Nearly half of Concremat’s contracts with the City were signed without going through competitive bidding processes, as “emergency works.” The emergency contracts with Concremat alone amount to R$409.3 million, R$12.3 million of which were for seven projects for the Olympics. Overall, since the beginning of the Paes administration, 46.3% of contracts have been executed as emergency works.

A common criticism is that a large portion of these works have been carried out with greater consideration of image than safety and function. In December 2014, workers on the bike path construction protested against inadequate working conditions, including a lack of proper equipment and safety precautions.

Following the bike path collapse, Paes was quick to assert that image is not the primary concern in assessing the aftermath of the bike path collapse. However he went on to say: “It’s unlikely that you’d see the Instagram of a Rio resident who doesn’t have a photo from this bike path.” As a recent RioOnWatch piece explores, the city has been lauded for some recent programs through a series of international awards, but a closer look reveals that these are often superficial changes (if changes are implemented at all) “for the English to see.”

One of the most controversial of the mayor’s actions in the preparations for the Olympics has been the forced removal of residents of Vila Autódromo. According to Rio Transparente, the first contract that Concremat fulfilled with the Paes administration was to develop technical assistance for government projects in favelas like Metrô-Mangueira and Vila Autódromo, both removed for the World Cup and the Olympics respectively. This contract was also awarded as an “emergency” contract, without competitive bidding.

Following the bike path collapse, protests were organized on Facebook, including a protest on bicycle by Rio’s Critical Mass, part of an international cyclist movement. They wrote on their Facebook invite that (a well-built) bike path is a long-time desire of Rio’s cyclists. “Today, we pedal for lives lost in the incident (and not accident), for the City Government’s neglect of the lives of those who use bicycles, and for more safety in transit for people (and not cars).”

Bike Path for Whom?

With a mere three months of use, it is hard to know exactly to what extent residents of surrounding neighborhoods were using the bike path as a mode of transport. However, last Thursday after the fatal death of Rocinha resident Ronaldo Severinho da Silva, 60, his wife, Eliane said, Ronaldo often would “go for a ride” on the bike path and on that particular day he was cycling from Rocinha to Copacabana and back. According to his cousin, Marco Antônio, Ronaldo was a hard working man who became “used to cycling on the bike track.” Another resident of Rocinha, Michel Silva shared on his Facebook page: “I already imagined that something bad could happen [on the bike path]. The part that collapsed had imperfections… Now I am afraid to use that path to go to work or university. It’s sad.”

On the Maré Vive community Facebook page, residents compared the Tim Maia bike path with the bike path installation in Complexo da Maré. The Tim Maia bike path, which was 4km in length and cost over R$44 million, opened in January. Maré’s cycle path, at 22km long, cost R$7 million and took one year to be “ready.” Residents assert that the Maré bike path looks like it was hastily painted, and is already so faded that it is no longer visible from the road. The Facebook comment highlights, “in both cases it is a classic diversion of money… The difference is they will spend the money to remake the Niemeyer track but the topic of Maré’s bike track won’t even be considered by the government.”

Others made use of social networks in the wake of the bike path collapse to express their dismay that a game of beach soccer continued as two collapse victims’ bodies washed up on the shore. While a priest with some two million Twitter followers said the image and situation “leaves us all less human,” others pointed to the general desensitization towards death that takes place in favelas experiencing high rates of police violence and armed conflict. Reportedly, a boy at the scene told the photographer of the now well-circulated photo, “in the favela this happens every day.”

Rebuilding

City council member Teresa Bergher from the Democratic Social Party (PSD), requested that the court enforce immediate suspension on all projects of Concremat/Concrejato and strongly believes that the cycle path should not be rebuilt. She argues it is “irresponsible… after such tragedy… in a place that is [evidently] not secure… I’m going to take action to stop this insanity [to rebuild]” and ensure the track is “demolished.”

Ana Teresa Nadruz, the aforementioned architect who specializes in engineering project management, launched a public petition last Wednesday in favor of having the whole route demolished. The petition argues that the bike path puts cyclists at risk due to the route’s positing between the sea and rock face. By Wednesday afternoon the petition had obtained almost 400 signatories.

On Monday April 25, Paes announced the reconstruction of Tim Maia bike path will take place and completed before the Olympics starts on August 5. At a press conference, the mayor stated: “We want to maintain the bike path. We will make the necessary adjustments to it. It is clear that a contingency plan is needed. In times of very strong waves, people will need to be warned not to circulate on the site.” He ensured that experts will create closure procedures in case of inclement ocean conditions.

The Concremat consortium itself released a statement on Sunday April 24 that “an internal investigation into the involvement of independent consultants is underway, in order to assess whether any activity under the responsibility of the contractor contributed to the accident.”

The final report reviewing the bike path’s construction is scheduled to be completed by the end of May 2016 by experts at the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Auditing Court (TCM-RJ).

Whether or not the bike path is ultimately rebuilt, it is clear that the partial collapse, and what Brazilians are decrying as an avoidable loss of life, will not be soon forgotten. The official Facebook page of the Tim Maia bike path has turned into a sounding board for Rio residents to voice their frustration and sadness. One wrote, “Brazil doesn’t need volcanoes, earthquakes, hurricanes or tsunamis. We have politicians and bike paths.” Many of the Facebook comments imply that the tragedy is symbolic of the collapse in political institutions and the less concrete, but deeply felt, disinvestment in the quality of life of citizens on several fronts, while politicians’ pockets continue to get lined. The broader implication is that perhaps “rebuilding” should start there.