Following last month’s reconfiguration of the Federal Planning Ministry following President Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, questions regarding the status of uncompleted infrastructure projects funded under her administration remain unanswered. Within a day of taking office, Interim President Michel Temer and Planning Minister Romero Juca eliminated the managing department of the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and introduced a new infrastructure initiative, the Growth, Employment and Income Generation Program, known as “Crescer.” While the Crescer program has effectively replaced PAC in overseeing federal investment in large public works, President Temer’s administration has yet to definitively address whether projects funded under PAC will continue to receive funding through Crescer.

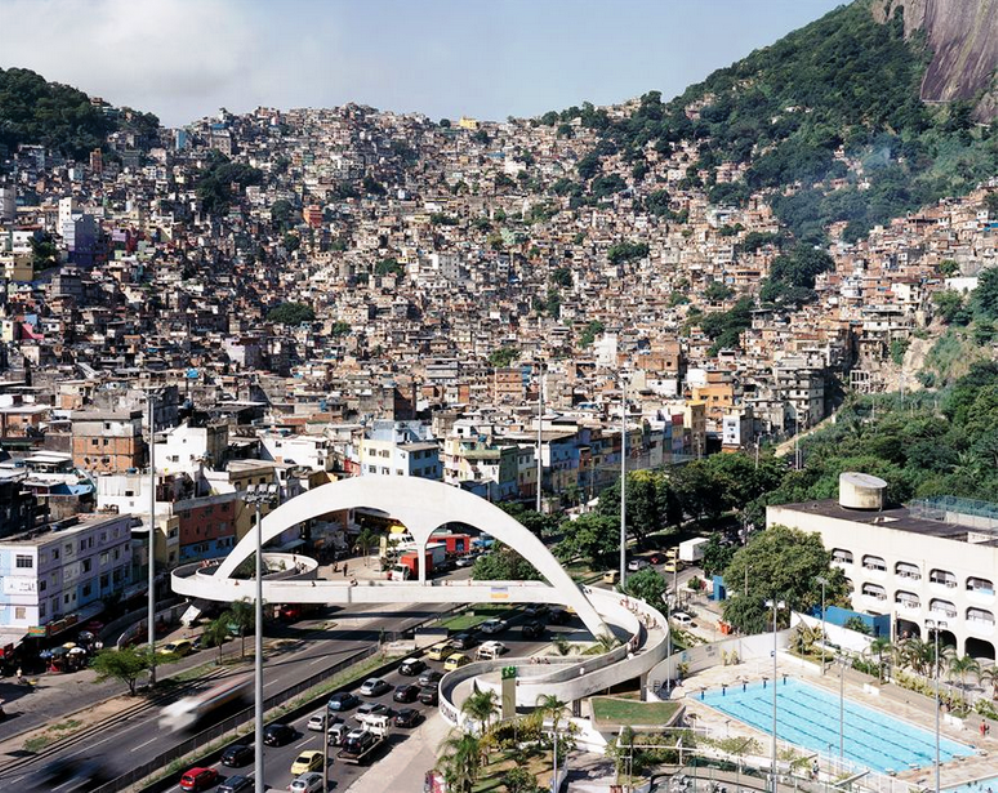

Among the hundreds of PAC projects currently at risk of losing funding is the longstanding effort to deliver infrastructure upgrades to Rocinha, Rio’s largest single favela.

Nearly eight years after the PAC was brought to Rocinha to inject billions of reais into upgrading projects, the program now sits paralyzed. Completed projects from the first phase of PAC do not include urgently needed sanitation projects which were expected in the next phase. While the future of these works remains unclear, residents and planners alike defend these works as an essential step in improving health, safety and quality of life in Rocinha.

PAC Overview

Established by President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva in 2007, the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) invested in large-scale infrastructure and urban development projects throughout the country to create jobs, stimulate private-sector growth and promote development. By 2014, the federal government had invested over US$1.22 trillion in these projects.

Among a number of projects in Rio, the first phase of PAC (known as PAC 1) provided funding for upgrading projects in three of the city’s largest favelas: Complexo do Alemão, Manguinhos and Rocinha. The projects in Rio’s favelas were modeled on the landmark, limited-success but very important upgrading program Favela-Bairro, which operated from 1994 to 2008, and overlapped with efforts by the city government to install public works in communities through the Morar Carioca program, which was introduced by Mayor Eduardo Paes in 2010, though later abandoned. While the budgets for PAC I projects in Complexo do Alemão and Manguinhos were partially funded by the state government, PAC projects in Rocinha received near complete funding from the federal government. Rocinha subsequently became a site of interest for visits by President Lula in 2010 and President Dilma in 2013.

PAC projects in Rocinha

PAC 1 in Rocinha received a budget of R$259 million, and since 2008 funded the construction of a sports complex, a public health clinic, a pedestrian bridge designed by Oscar Niemeyer, a library, and the redevelopment of Rua 4, now one of the community’s main thoroughfares. At the time Rua 4 was exceptionally narrow and consequently experienced the highest rate of tuberculosis in the state of Rio. Though this redevelopment project alone required the removal of over 800 homes, it was clearly undertaken to benefit residents’ health and displaced residents were offered money to purchase a home in Rocinha or an apartment in the new Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing units constructed on essentially the same site along Rua 4. As a result, the vast majority of residents displaced by those initial PAC projects remain in Rocinha today and the Rua 4 housing is seen as one of few recently-built successful examples of public housing in Rio.

The second phase of PAC (PAC 2) was planned to invest R$457 million in popular sanitation and less popular accessibility upgrades. Though the most visible component of this phase is the installation of a cable car system, slated to cost R$152.2 million and widely contested by residents, the majority of funds have been allocated to upgrade existing infrastructure. Four streets (Rua 1, Rua 2, Rua 3 and Rua do Valão) are to be upgraded in the same manner as Rua 4 in an effort to improve accessibility for pedestrians and emergency vehicles. In the case of Rua do Valão, the redevelopment will also cover the open sewer that runs the length of the street, possibly ameliorating public health concerns for residents. These plans to widen and upgrade main thoroughfares will involve the installation of storm water systems, develop sewerage infrastructure and lead to more regular trash collection.

Though the plans were completed years ago, PAC 2 projects in Rocinha have been paralyzed since February 2015 when ex-Minister Joaquim Levy announced a budget freeze on PAC investments due to the economic crisis. In recent months, officials have articulated that construction in Rocinha could feasibly begin by the end of the year, but that the political turmoil at the federal and state levels could threaten this.

Delays, lack of transparency and concern over priorities

The current delays are not the first to impair PAC investments in Rocinha. Reports from as early as 2011 describe budget freezes that stalled projects for months or years at a time, leaving residents and observers confused and frustrated. Designated PAC 1 projects have since been completed, while a series of “complementary” projects that received funding in later budget cycles are near completion. These include a kindergarten, a public market and a funicular tram with three stations on the northwest side of the community. Despite the eventual completion of these projects, the confusion around their fate reinforces an underlying problem of transparency. Residents complain that the lack of information leaves them little opportunity to participate, echoing a broader problem with recent government actions in Rio’s favelas. Due to poor consultation procedures, in particular with regard to the cable car, residents’ disagreement with intended works has been pronounced, particularly through the advocacy group Rocinha Sem Fronteiras. This movement has been lobbying for sanitation and against the cable car since early in the process, pointing to the cable car as a high-cost marketing project, the high number of evictions and the potential of the project to produce gentrification.

While residents debate on their own through Rocinha Sem Fronteiras, EMOP, the public works company responsible for coordinating PAC projects throughout the state of Rio de Janeiro, officially insists on the importance of community participation and transparency in the planning process. EMOP representatives describe how they spent two months in Rocinha completing a “social diagnosis” on the specific infrastructure and service priorities for the community, with a planning process involving 12 public meetings between planners and residents, and a census of residents, homes, businesses and organizations. EMOP also consulted, but did not adopt, the Master Plan developed by architect Luiz Carlos Toledo, who over the course of five years conducted intensive research and moved his office to Rocinha to work directly with residents.

Ruth Jurberg, who has served as the general coordinator of the social component of PAC in Rio de Janeiro since 2007, described the planning process as fundamental to establishing trust between the government and community members. She claims many favela residents were skeptical of the government’s presence after decades of neglect, until her team undertook their work there. Now Jurberg fears that “we are losing their trust once again. They don’t trust us anymore. They created these projects with us and had the hope of transforming their communities, but now everything has stopped.”

José Fernandes, known as Xavante, is a lifelong Rocinha resident and former president of the Rocinha Residents’ Pro-Improvements Union (UPMMR). He maintains that overall PAC’s upgrading projects have improved the quality of life in Rocinha. Upgrading, he explained, improves the sanitation and health of the communities, and also promotes public safety and upward mobility by introducing public services such as cultural programs and schools for children and more accessible clinics for families.

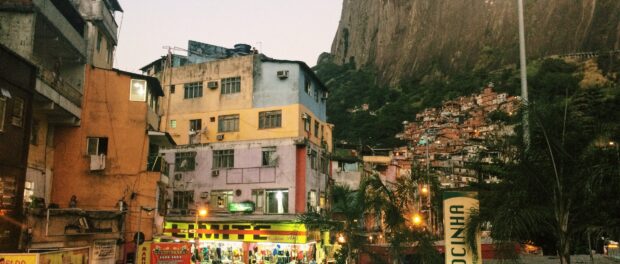

“It’s very sad to see this community in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, with all this wealth on one side in São Conrado, while thousands of residents here live in miserable conditions.” He reiterated the significance of these programs as the first indication that the government was committed to improving conditions in Rocinha and described the long struggle to procure basic services and dignity for residents. “Rocinha has been fighting for these works for years–nothing comes here without a fight,” he said.

Xavante is joined in his support of the program by residents in the Minha Casa Minha Vida public housing development adjacent to Rua 4, who expressed contentment with the upgrading projects, explaining that the area was cleaner and healthier than it had been before PAC.

“I’m very satisfied, because compared to where I used to live, there is much more dignity here–the trash is collected several times a day, ambulances can get through the street, it’s much better,” said Fabiani, whose home was removed during the redevelopment of Rua 4.

Employees of the Biblioteca Parque (Park Library) proudly touted the free educational and cultural classes offered to residents and showcased the facility’s resources, which thousands of residents use every week, though they communicated their concern that the library has been under threat of closure several times over the past year due to lack of public resources.

Though residents complain they are often understaffed, the public health facilities–a family clinic and an urgent care clinic–are centrally located and significant additions to the healthcare services of the community.

Dozens of residents interviewed agreed that the investments made in PAC 1 were a step in the right direction, but far from sufficient to solve the myriad health risks posed by insufficient garbage collection, sewage systems, and storm water drainage. The consensus was that PAC 2 projects are vital to improving sanitation in the community.

Current status

The realization of PAC works in Rocinha now depends on political stability at the state and federal level. EMOP has suffered a series of debilitating budget cuts from the state, with some fearing the entire department could be closed in coming months. It is unlikely that PAC could continue to operate in the state of Rio de Janeiro if this were to happen. At the federal level, funding is contingent on political will. PAC remains heavily associated with the Workers Party (PT), which means continued funding by the new administration following Dilma’s impeachment could be jeopardized. Jurberg suggested that prospect of funding the Rocinha projects under President Temer was bleak, stating before the final Senate vote, “If something happens in terms of the impeachment I think there’s a good chance this project could end.”

If the situation holds, with both EMOP and the PAC 2 Rocinha budget intact, the process for starting these projects could move quickly. Caixa, the federal bank responsible for overseeing the contracts for PAC, could liberate bids for the PAC 2 projects in Rocinha in the next two to three months, meaning construction could theoretically begin as early as September. The first project to break ground would be the redevelopment of Rua do Valão, which has been an upgrading priority for decades.

Given the current political situation, the fate of PAC 2 in Rocinha appears to hang in the balance. Projects are simultaneously tantalizingly close to breaking ground and an inch away from being revoked entirely. What has already involved eight years of planning and anticipation could very quickly crumble. For residents, PAC carries the promise of delivering essential sanitation upgrades and expanding social services, and a failure to complete these projects would represent both an egregious failure of government and a debilitating setback in the efforts to improve living conditions in Rocinha.

Jody van Mastrigt contributed reporting