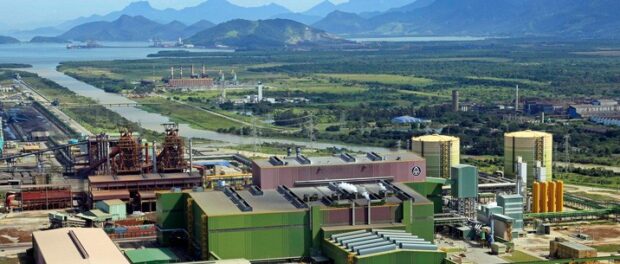

The Companhia Siderúrgica do Atlântico (CSA) is a joint venture between Brazil’s mining giant Vale do Rio Doce and the German multinational group Thyssenkrupp. Its steel plant occupies an area of 80km² in Santa Cruz, on the shores of the Sepetiba Bay in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro. It is the largest steel processing facility in Latin America and one of the largest private industrial undertakings implemented in Brazil in the last decade. However, it has been facing a long and controversial environmental licensing process.

Also known as TKCSA, acronym for Thyssenkrupp Compania Siderúrgica do Atlântico, this huge steel processing complex was built in the Sepetiba Bay area, a region traditionally known for artisanal fishing, small-scale agriculture and tourism. The area around the bay used to be surrounded by native mangroves and was home to communities originated from quilombos (established by or descended from enslaved Africans), indigenous peoples and artisanal fishermen. However, this reality was completely disregarded in the plans for “local development.” From the 1970s onwards the installation of heavy industry was encouraged by the government, including the Ingá Mercantil, the Itaguaí steel-making company, and now TKCSA. Even before starting to operate, the installation phase which included the construction of a harbor at Sepetiba Bay had various negative social and environmental impacts on the region. Both the touristic potential and artisanal fishing activities have suffered due to the destruction of part of the local mangroves and the creation of an area where fishing is prohibited with a radius of up to 500 meters from TKCSA’s harbor.

Metallurgy is considered by law to be an activity with high chances of polluting. In its production process, solid waste and a number of air and liquid pollutants are released. Polluting effluents result from the cooling and processing system of toxic gases, which are the byproducts of the manufacture of coke and contain high levels of ammonia and benzene. This material requires the construction of treatment plants, along with great caution regarding the disposal of the treatment’s by-product, a sludge with high concentrations of heavy metals. Exposure to some of the most toxic of this waste raises the risk of respiratory cancers and heart problems, as well as long and medium term damage to the immune and central nervous systems.

The period from the presentation of the Study and Environmental Impact Report (EIA/RIMA) in 2005 to the start of the operation of the first blast furnace in 2010 was marked by controversy and protests against the implementation of the project. The company was fined R$1.8million within less than six months of operation for polluting the air of the residential areas neighboring the plant. According to CSA, a malfunction in one of the machines would have forced the company to dispose of pig iron in an unroofed compartment, inappropriate for such. The particles were scattered by the wind around the plant, reaching approximately 6,000 homes. The incident became known for its “silver rain.” In addition to fines, the State Environmental Institute (INEA) established the need for the installation of two additional stations monitoring air quality.

After the “silver rain” incident, CSA’s projects director and environmental manager were accused of environmental crimes in a lawsuit by the Rio de Janeiro State Public Ministry. The crimes included causing pollution that could result in damage to health and presenting fraudulent environmental studies.

TKCSA, which has not yet had its operating license issued, has been active since 2012 under the legal basis of a Conduct Adjustment Term (TAC) prepared by the State Environmental Institute (INEA), but without the recognition of the State and Federal Public Ministries. In April 2016, the Federal Public Ministry (MPF) and the Public Ministry of the State of Rio de Janeiro (MPRJ), represented by GAEMA (an action group specialized in environmental causes), along with the Rio de Janeiro State Public Defenders (DPERJ), dispatched a recommendation to the State Environment Secretary, the State Commission for Environmental Control (CECA) and INEA not to grant Thyssenkrupp the operating license, except by means of a regular environmental licensing process.

The Conduct Adjustment Term (TAC) isn’t a substitute for an operating license. It only defines the adjustments the company must carry out to be able to operate, without considering the impacts, alternatives and compensations. Despite TKCSA not having carried out all the 134 established clauses, the TAV was renewed twice. It’s evident that the pressures of political and economic interests, especially those behind large corporations, still has a strong influence on the environmental licensing process. TKCSA’s current TAC expired in April 2016.

On April 5, the State Legislative Assembly (Alerj) Human Rights Commission held a public hearing to discuss the issues inherent in the process. The Chairman of the Committee, Marcelo Freixo, moderated the hearing, in which representatives of both sides as well as government agencies had the opportunity to speak.

The hearing was opened by Karina Kato, PhD in Development, Agriculture and Society and a member of PACS, a non-governmental institute that researches alternative policies for South American countries and which leads the movement “Stop TKCSA.” Karina opened her speech questioning, “as a company with two criminal lawsuits, with 238 actions filed by the Public Defenders’ Office, how can it have operated for six years, since 2010, without an actual operating license?” Karina argued that “The TAC is not an operating license. It is an instrument for the company to adapt and operate in accordance with environmental legislation. What’s happening is a relaxation of environmental licensing.” Nevertheless, “since 2011 the CSA has been operating at 80% of its total production potential.” She recalled that the TAC has been prepared without a public hearing and emphasized that no chemical analysis of the gaseous emissions of the plant has been made accessible to the public.

Next, Jaci Nascimento, a local fisherman, spoke on behalf of the fishermen of the region. “There are no fish for us to work in order to survive. Also, the dam built by CSA prevents us from passing through the harbor with our small boats. There’s no way we can pass through the port of TKCSA, and sail to where the fish are. Because of the pollution in the mouth of the São Francisco river, the fish no longer approach the area where we used to fish. We are fishermen, we depend on fishing to earn our livelihood and support our families.”

The next to speak was a resident of Santa Cruz, Margarete dos Santos. “Unfortunately, from 2010 on, when CSA’s plant started its activities and as the ‘silver rain’ fell and invaded our homes, health problems have increased among people where I live. Our health has been affected, so has our environment, our trees are dying. In my family, there are people who have worked for CSA, who are now sick with pneumonia, tuberculosis and hypertension. Ask the agents at the health care centers what the situation is like.” She stressed that the TAC cannot be “renewed in these conditions without reviewing the points which have not yet been complied with… CSA has paid fines to INEA, but they are of no value for our community. Health care centers do not have medical experts. You have to wait up to two years to get an examination done. For a consultation with a doctor (at the Family Clinic), you have to wait for months.”

Next to speak was a CSA employee and resident of the area. As a resident of Santa Cruz for the past 20 years, she stressed that “we cannot ignore the benefits brought by the company to the region.” However, she also mentioned the silver rain, “Every time it rains, my house and my yard turn black, covered in black dust. The train passes less than 100 meters from my house. This, at first, did not bring me any illness.” She added “it is not only CSA that pollutes the area, there are other plants as well.” She continued, saying that the “lack of medical experts is not only a problem in Santa Cruz, it is a problem in the whole country.” She shared, “I came from Manaus to Rio. I am a single mother. Working for Thyssenkrupp enabled me to finish college and get a post-graduate qualification. Now I am about to have my second child and am receiving full support from the company… To conclude I would say that, yes, there is still a lot to improve, but it is not only one company that causes pollution, there are several of them.”

The director of the National School for Public Health (ENSP) at Fiocruz, Hermano de Castro, mentioned some points from the report prepared and delivered to INEA for analysis. Fiocruz monitors and researches the impacts from the company’s facilities, and prepared a report–Updated Analysis of Arising Health, Social and Environmental Problems Related to the Operation of TKCSA–containing facts, such as the increase in cases of cardiorespiratory diseases in the region in the period after the plant started to operate. Moreover, the report reinforces the need for medical specialists at the health centers in the region. The documents produced by Fiocruz do not agree with several points of the TAC, and supports that these must be re-studied and reworked considering the data submitted by Fiocruz. He cited the study by Adriana Gioda, a researcher at the Rio’s Pontifical University (PUC), relating a possible increase in the carcinogenicity potential of the region with the presence of certain elements detected in the air surrounding the plant. He also mentioned that, “for cancer, there is no minimum exposure limit; even the lowest levels can cause disease. Cancer will not show up within two or three years. It appears 10, 15, 20 years later.” He also suggested the “implementation of a health status monitoring program in the region for the next 30-40 years.” And added, “because this is the time that it takes for cancer to develop.”

CSA’s CEO, Pedro Teixeira, gave the next speech. He began by referring to Dr. Hermano, from Fiocruz, inviting institute representatives to visit the plant. He also mentioned that, “unfortunately, in the past, the first contact with Fiocruz was not the best. However, we recognized our error and withdrew the legal actions against Fiocruz.” He said that the plant’s facilities have “the most advanced equipment engaged in the reduction, treatment and monitoring of emitted pollutants.” He referred to the TAC stressing that it is “a complete and rigid document,” and that the company has over the years been making “significant investments to adapt its operations to the requirements of the Term.” He said: “CSA will be able to complete the environmental licensing and receive an operating license.” At the end of Pedro’s speech, the moderator Marcelo Freixo asked him what the current production rate of the plant is. Pedro said: “Today we operate at 80% of our total capacity.”

The hearing continued with a speech by State Environment Secretary André Correa, representing INEA. He confirmed some of the plant director’s claims, mentioning that the last “silver rain” incident took place in 2012 and that benzene emissions are monitored by INEA and are within the standards required. On the other hand, he mentioned that the “de-dusting” (installation of appropriate filters) of the furnace had not yet been completed–a fundamental condition for issuing the operating license–and that the current form of water abstraction from the São Francisco river will no longer be allowed. At the end of his speech, André commented on the fact that INEA is not properly “prepared to analyze public health matters” and called for the “cooperation of Fiocruz in this regard.”

Thaisa Guerreiro, coordinator of collective health guardianship matters at the Public Defenders’ Office, argued that the company is unable to fulfill the provisions of the TAC. She also referred to the Environment Secretary’s comment, saying INEA cannot dissociate public health from environmental issues, reinforcing the importance that the public body “must be able to examine aspects of both natures.” She also mentioned the recent “presentation of a public legal action to question the installation of a threshold (submerged dam) on the São Francisco canal in the Sepetiba Bay,” whose construction had been authorized by INEA and the Brazilian Navy “without conducting an impact study on the fishing activity in the region.”

State Prosecutor Sergio Suiama commented on the claims against the directors of CSA and representatives of INEA, disagreeing with several points of the licenses already issued (preliminary and installation licenses), in addition to emphasizing the non-approval of the TAC by the Federal Public Ministry.

Vanessa Martins, a public prosecutor from the environment specialist working group (GAEMA) at the Rio de Janeiro State Public Ministry, referred to a criminal legal action regarding the transparency of the environmental audit carried out by a company contracted by CSA and which is the basis for the decisions made by INEA in terms of the TAC licences.

The tension between State Prosecutors, the Public Defenders and INEA was more than evident. Both the State Prosecutors and Public Defenders criticized the State Environment Secretary for being too “flexible” and for the lack of transparency by INEA.

A further employee and resident of Santa Cruz expressed his opinion. He pointed out the benefits of the project to the region in terms of the generation of jobs, increased security for the site, paved roads, and the building of schools and health clinics. It is, however, important to note that all these improvements are compensatory measures for enterprises of this size and nature. The plant currently has a staff of 6,000 employees and, obviously, all fear for their jobs.

One of the residents to speak in favor of the plant, a woman who has lived in the area for over 50 years, talked about the improvements brought by the project. She argued, “Santa Cruz has always been an area degraded by industrial enterprises and abandoned by the authorities,” and questioned the sudden concern raised towards the area since the construction of CSA’s steel plant.

At the end of the hearing, the Human Rights Commission requested the State Environment Secretariat allow “public online access to all documents related to the environmental licensing processes of CSA, the TAC, and the construction of the (underwater) sill in the São Francisco canal.” The Commission also expressed its “displeasure at INEA’s new addenda to the TAC, or the granting of any permit or license until all environmental regulations are met,” and added that its compliance must be evaluated by Fiocruz, and the State and Federal Public Ministries.

On the same day of the hearing, the State Commission for Environmental Control (CECA) issued an authorization of operation for Thyssenkrupp. The document authorizes TKCSA to continue to operate for 90 days after the TAC expiration date, on April 16, 2016.