On Thursday, June 23, environmental journalist Emanuel Alencar released his book Baía de Guanabara–Descaso e Resistência (Guanabara Bay–Neglect and Resistance) at a public launch event at the Brazilian Institute of Architects in Flamengo in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Alencar was joined by environmentalist Sérgio Ricardo, and together they held a public discussion about the pollution of Guanabara Bay.

Alencar synthesized 30 publications, scientific papers, and official reports, and included interviews with researchers, fishermen, civil servants, and other environmental activists for his book. The discussion at the launch event was moderated by O Globo journalist Flávia Oliveira and hosted by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Brazil’s president Dawid Bartlet, whose organization co-published Alencar’s book with Mórula Editorial. Bartlet’s introduction provided the professional background of each panelist and explained the importance of responding to the pollution in Guanabara Bay.

Alencar synthesized 30 publications, scientific papers, and official reports, and included interviews with researchers, fishermen, civil servants, and other environmental activists for his book. The discussion at the launch event was moderated by O Globo journalist Flávia Oliveira and hosted by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Brazil’s president Dawid Bartlet, whose organization co-published Alencar’s book with Mórula Editorial. Bartlet’s introduction provided the professional background of each panelist and explained the importance of responding to the pollution in Guanabara Bay.

The state of the bay has been an official part of political agendas in the city since Rio’s 1992 Earth Summit and around R$2.5 billion have already been invested in managing the pollution. Studies have shown that up to R$15 billion will be the minimum cost for completely preventing the flow of sewage from all neighboring municipalities. In the past, public statements made by politicians about cleaning the bay have been revealed to be empty promises over time, because frequently there have been guarantees that the bay will be clean without any use of existing scientific studies to support claims about the cost or length of time necessary.

The failure of the city government and the need for transparency were major components of Alencar’s argument. And yet even if productive laws get approved, another equally important part is improving public awareness about environmental issues. “There is still a long way to go,” he says, “to be able to apply the law in a comprehensive way. But furthermore, you still have the whole North Zone region, which is one of the poorest regions, and they struggle just to build the infrastructure for proper disposal. There is still a long way to go with regard to the participation of the population.”

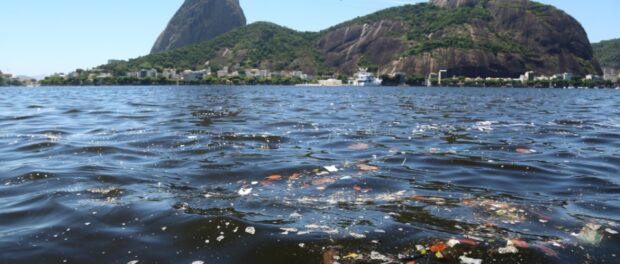

Another major concern is the Olympics sailing events, and the possibility of floating waste obstructing the sailboats during a race. 15 of an expected 17 eco-barriers have been built around the bay, which have so far been able to eliminate 280 tons of waste from entering the bay per month. But the bay isn’t threatened by just the raw sewage—the majority of trash in the street throughout the city eventually gets washed into the bay as well. Solving this issue, Alencar explained, is much easier when confronting the source of pollution, which means changing the actions of citizens. The revitalization of Guanabara Bay will require not only improvements to sewerage systems, but broader education campaigns that can teach the importance of individual environmental responsibility.

The other panelist, environmentalist Sérgio Ricardo, is a leader of the Baía Viva (Living Bay) movement, which is dedicated to fighting against the degradation of Guanabara Bay. He claimed that 90 tons of trash flows into the bay every single day and argued passionately against the current situation.

One of Ricardo’s biggest concerns was the impact the pollution is having on local fisherman. “Fundamental areas for the survival of fishing are completely decimated,” he noted, describing the long hours and hard work fishermen put in every day. “There are so many tough fishermen out there. I want to acknowledge all the fishermen,” he said, which prompted some of the loudest applause of the night.

A slideshow in the background showed pictures of the devastating environmental damage already done to Guanabara Bay. One of the most memorable images was a protester standing on a beach surrounded by garbage, wearing a shirt saying “I don’t want just a postcard.” The panel concluded arguing that slow but permanent progress will be better than temporary superficial changes designed to create a “postcard image” of Rio for Olympic tourists and visitors.