Human rights by definition should, well, be applied to all humans. In practice, however, they are distributed unevenly and sometimes even regarded as something “deserved” only by some. In a series of interviews with residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and gated communities on the subject of basic services that should be guaranteed as human rights—such as education, healthcare, sanitation, and a fair justice system—some interviewees described a social contract in which contributing to society is expected or even required in order to “earn” rights to basic services. This is counter, of course, to the very concept as guaranteed by the UN Declaration of Human Rights or, in this case more directly by the Brazilian constitution itself.

Citizenship, often thought of simply as anyone holding citizenship to a nation, is actually an ambiguous construct. Anthropologist James Holston refers to a concept of “differentiated citizenship:” although citizenship supposedly brings equal rights to all, in practice it reflects historical inequalities. The distribution of rights is not only about what is written in a constitution, but about how these rights are in fact applied, often based on inherited understandings of who in a given society is seen as worthy. Those who don’t pay taxes on the periphery may be seen as less deserving, as might those involved in criminal acts.

Gated community perspectives

Interviewed residents of gated condominiums expressed frustration with having to pay for their own security, healthcare and education. They argued that the walls and security guards protecting their community were necessary to live a “normal” life without worrying about children playing outside, going for a run in the evening or being robbed. They also framed private healthcare and education as necessities, as the quality of public services is lacking. They expressed feeling cheated for paying “double” by way of paying both taxes and for the private services that should have been provided in exchange for those taxes.

Furthermore, there were many complaints about public infrastructure: the roads that connect Barra da Tijuca to the South Zone and Centro—the places many of them work or go for pleasure—are always jammed with traffic, while sewage often goes untreated and pollutes surrounding waters. Several critiqued the world-recognized direct cash transfer welfare policy Bolsa Família, while suggesting that investments in quality education and health would be more effective to reduce poverty in a better way and thus stimulate a stable country. Overall, the Barra residents interviewed expressed the feeling that they are entitled to better services and more efficient government spending given the amount of taxes they pay.

Favela perspectives

Favela residents struggle even more with the lack of quality public services, and their means to seek private solutions are considerably more limited, though their resourcefulness to make up for this public mismanagement is world famous. In many ways they bear the brunt of the dysfunctional public security policies, with some favelas facing a combination of threats from police, militia and traffickers. They also often lack the funds to pay for quality private education or healthcare. Favela residents too feel wronged: many argued in the interviews that they are an under recognized constituent of society, stigmatized despite contributing with their labor and cultural production to building the city of Rio, not to mention paying heavy taxes themselves via Brazil’s high sales tax, a heavily regressive tax.

Many of the government projects stated to be intended to improve life in the favelas after decades of neglect were greeted with hopefulness but, on witnessing their impact on the ground, their second agendas became clear to residents: that the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) were a tool to foster real estate speculation, streets are widened only to enhance patrol-effectiveness and facilitate forced evictions, that the Olympic Games benefit only the rich, that the PAC investments in Rocinha, Manguinhos and Alemão are “for the English to see.”

A common theme throughout interviews with favela residents was that key services or works are brought about by residents themselves. Maria*, 46, has lived in Asa Branca in the West Zone since she was a child. Reflecting on the neighborhood’s development over the years, she says: ”The community is a thousand times better than it was before, it’s incomparable. But this was not because of the government. The work has been done for years by people here. Our neighborhood association did the work, it is because of them and not the government. Without the association it wouldn’t happen.”

Bruno, who runs a computer repair shop in Asa Branca, has lived there for 31 years and remembers the old days too: ”The community has evolved. When I arrived here the roads were not paved. Not all people in Asa Branca are aware that it got so much better. We grew because we put force behind it, it didn’t happen naturally. The government helps to develop the community, but could definitely help more. We are not [their] priority.”

“It’s a history of struggle,” community leader Carlos Alberto “Bezerra” Costa underlines. ”Basics like sewerage and houses are self-built. We have everything, but it’s difficult. A daily struggle.”

Erik from Rocinha makes a living as a tour guide and echoes the Asa Branca residents: ”Rocinha was formed by former slaves who came here after abolition. Together they fought for government services and recognition. These are the people that built Brazil, they built the cities. They also built their own neighborhoods. All these different people are fixers, making things that people in the community need like electricity and water systems, building houses and renting them.”

As for security, the favela residents interviewed generally did not believe government services were meant to benefit them. Many distrust the police and see it as an institution that serves the society outside of the favela. ”Many are ambiguous about the influx of police forces,’’ Pedro from Rocinha, 32, explains. ”I don’t think it was from a community goal, it was a security idea. They widened roads to patrol better, not for air circulation or traffic. Otherwise they will get lost. They come here with their judgment, especially when you’re black. Many people hate the UPP. Officers are rude, arrogant, don’t really care for Rio. They don’t have a connection with the community. And the traffickers had that! You knew their mother, they were more there for the community. Their business was bad, but they helped those who lived here for a long time and worked.”

Luckily, Asa Branca faces few negative influences from trafficking: ”It’s calm,” Sabrina, 40, says. ”In other neighborhoods you have people with guns, selling drugs, but thank God not here. You can sometimes see it happen, but they do not bother us.” Still, Asa Branca residents recently installed cameras in the run up to the Olympic Games, preparing for the risk that an increased number of strangers and biased police forces would enter their neighborhood. For this community, there’s a sense that residents have to provide security for themselves.

The government’s failure to provide basic rights

Having to “fight the system” rather than simply “claim what’s theirs” for basic rights is an obvious frustration and many favela residents feel wronged by the government’s failure to guarantee their rights. Like the condominium inhabitants, they emphasize that they contribute a lot and get little in return. Igor from Asa Branca, 31, says: “For example, the PVA [car tax to maintain the roads]: we pay a lot but unfortunately the roads are terrible. We pay a lot of taxes meant, for example, for hospitals. They don’t have the basics: bandages, no, injection, don’t have it, IV, not there. So you still have to buy them, because the hospitals don’t have it.”

Pedro from Rocinha emphasizes both the economic contributions of favela residents—”If we stopped working, Rio would stop”—and non-economic contributions: ”This is where Brazilian culture comes from. Art, samba, funk. It’s part of Brazil.”

Maria from Asa Branca also feels like the give-and-take is crooked: ”The education is a façade… The government is taking more than it’s giving, it’s exposed for everyone to see here. There are people receiving Bolsa Família, some families benefit. It’s more to keep children in school, which is interesting. I did receive some help when I went to the hospital with the baby, but after a while the doctor wasn’t available anymore so I stopped going.”

Igor adds that the small business owners in and outside favelas are caught in a bad tax system: ”If you have a business, you pay a lot over small profits. In the US a start-up has three years tax-free, but in Brazil you have to pay for this and that from the first day. And to continue too, you need licences and things like that, and many go bankrupt because of this.”

Interestingly, while highlighting how basic services are often not guaranteed or designed for favelas, these residents all used the similar contribution-based rationale described in the gated communities, to argue they deserve more.

The tax factor

Even though human rights should be unconditional, residents of both gated communities and favelas put them up for debate by suggesting that “making a contribution” is a pre-condition to access.

People who participate in the informal market rather than more formal employment sometimes face accusations that they do not contribute to society because they evade taxes. Yet informality doesn’t necessarily mean participants are benefiting from lower costs, as a survey of 48,000 small firms highlighted. The informal enterprise faces 1.3 times more costs than a formal business due to production limitations in size and thus efficiency, lack of investment, and lower productivity. Not to mention fear of repression and, on occasion, seizure of merchandise.

“Research shows consumption taxes in Brazil actually counter the positive gains direct transfers make in reducing poverty.”

Furthermore, participation in the informal economy doesn’t even mean someone pays fewer taxes. Brazil has a paradoxical tax system. Its rates are relatively high and are similar to Western European welfare states: Brazilian taxes amount to 35% of the country’s GDP, two-thirds of which goes to welfare programs. This is far above the tax rates of other Latin American countries, but still the inequality in Brazil is often greater than those countries. This is mainly due to the regressive taxation system with a high level of indirect taxes, which means people earning lower incomes pay relatively more in taxes. Flat consumption taxes hit the poor harder as a percentage of their income. In fact, research shows consumption taxes in Brazil actually counter the positive gains direct transfers make in reducing poverty.

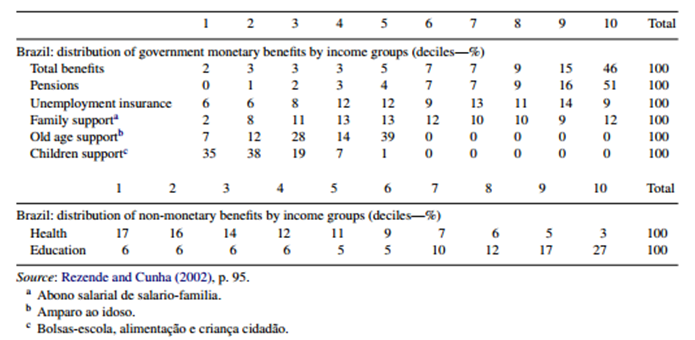

Even government welfare programs do not exclusively benefit lower income groups. Some programs are for economic shocks regardless of income, but the table above shows that nearly half of government monetary benefits serves the country’s top income decile. Half of total government expenditures goes to amortization of debt and debt servicing, which implies it flows into the coffers of banks and investment funds run by the wealthy. Thus, neither the notion that the poor don’t pay taxes, nor the idea that government programs are simply redistributing money to the poor, are accurate.

Looking to the Constitution

These facts about how Brazil’s tax system works are important for fighting the misconception that favelas are just tax burdens, rather than contributors. Stigmatizing favela residents as non-contributors legitimizes a continued absence of government services.

However, contribution should not even be an argument when talking about human rights. The contribution argument derives from a sense of injustice among both favela residents and wealthier condominium inhabitants, all of whom feel angered over a denial of quality public services, so it’s understandable people emphasize it. But this argument implies one must “deserve” human rights, which in turn legitimizes an unequal distribution of rights.

“However, contribution should not even be an argument when talking about human rights.”

Generations have fought for equal recognition under the law regardless of income, gender, or race, and for rights that apply to taxpayers and non-taxpayers alike, now embodied in the constitution. Using arguments like “we contribute in this way so we deserve these benefits” immediately weakens the position of human rights.

Instead of falling back on the same centuries-old claims that some people don’t deserve rights because they don’t contribute or pay for them, it’s time to focus on the rights defined in the constitution as the primary departure point for what all Brazilians “deserve.”

Christian Kuitert is pursuing a Masters degree in ‘Conflict, Territories and Identity’ at Radboud University, Netherlands, focusing on comparative citizenship in Rio’s favelas and condominium communities.

*Some names have been changed.