For the original article by Orlando Alves dos Santos Junior in Portuguese published by Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil click here.

The institutional political coup that resulted in the illegitimate ousting of President Dilma Rousseff represents a new turn to the right for Brazilian urban policy. However, instead of considering the president’s removal and subsequent impeachment proceedings an isolated event, the conservative bloc’s political coup must be seen as a process that was planned and carried out within Dilma’s own government, as evidenced by the shifts in position, shortly before the congressional vote, among parties and politicians once considered Dilma’s allies.

To understand the coup and its impact on urban policy, it’s useful to identify the changes in political climate that have taken place over time.

The late-1980s and the 1990s saw a sharp turn toward counter-reforms in Brazil. From the beginning of Collor de Melo’s presidency in 1989 through the two terms of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, an agenda of neoliberal structural economic policies began to take shape. The adoption of economic liberalization policies and the privatization of state businesses opened a new era of urban commercialization. As a result, by the year 2000, Brazilian cities were marked by divisions–which, as we know, have historical roots–and profound inequalities in social inclusion, citizenship, and quality of life. Conditions in the cities, and especially in the major metropolitan areas, began to deteriorate and the urban centers became economically polarized and characterized by fragmentation, division, violence, pollution, and environmental degradation.

The origins of this process date back to the exclusionary modernization of Brazil. As urbanist Ermínia Maricato put it: “From the beginning of the Republic we see modernist urban segregation.” But the most profound changes to the patterns of Brazilian urbanization began in 1950, as industrialization intensified through a combination of massive migration from the countryside to the cities, a concentration of the population into metropolitan areas, the expansion of the middle class, and the hiring of labor. Indeed, according to Maricato, “the urban legal apparatus in regards to land and housing, which developed in the second half of the 20th century, formed the basis for territorial exclusion and the beginning of the real estate market founded on capitalist relationships.”

Beginning in the 1990s, however, the patterns of Brazilian urbanization began to change, largely due to transformations taking place in international capitalism and the ways in which Brazil entered the process of globalization, as has been detailed in national and international literature. On one side, the widening of the periphery of large metropolitan areas, with population growth in the municipalities at the edges of the city and the expansion of favelas and irregular settlements; on the other, the emergence of middle class enclaves and gated condominiums on the periphery, rendering the urban space more complex, unequal, and heterogeneous. The model of production and management of Brazilian cities adopted during this period was the result of a combination of processes rendering the selective inclusion of competitive, dynamic regions into the international circuit of capital; the concentration of the population in metropolitan areas; and urban segregation and socioeconomic exclusion. Thus emerged a new socio-spatial order divided between rich and poor, between citizens and non-citizens.

At the same time, in institutional terms, the government had not adopted an urban policy. None of the successive governments ever articulated a strategic plan for regulating urban land, housing, sanitation, or mobility and public transportation in Brazil’s cities. Always fragmented and subject to the favoritism which characterized intergovernmental relations, urban policy was the responsibility of different federal agencies. Take the example of housing policy. Between 1985 and 2002, housing policy fell under the responsibility of six different ministries: from 1985 to 1987, the Ministry of Urban Development and the Environment; from 1987 to 1988, the Ministry of Housing, Urban Planning, and the Environment; from 1988 to 1990, the Ministry of Social Well-Being; from 1990 to 1995, the Ministry of Social Action; from 1995 to 1999, the Secretariat of Urban Policy, under the Ministry of Planning; from 1999-2002, the Special Secretariat of Urban Development, which reported directly to the presidency of the Republic.

By 2003, with the election of President Lula, urban policy was entering a new progressive phase. The Ministry of Cities was created as a response to an institutional void–the absence of a national urban development policy working toward a plan for sustainable and democratic cities. The creation of this ministry was a sign of the federal government’s recognition that urban issues were of national concern, to be dealt with by macro public policy. Indeed, a great deal of urban policy expertise is today decentralized, particularly since the 2001 approval of the City Statute, which consolidated and strengthened the role of municipalities in city planning and management. However, urban problems–including issues of housing, sanitation, mobility and transportation–in all their complexity, require national attention. The federal government continues to have a significant role to play. A national effort is especially important in the major metropolitan areas, as much in the establishment of directives as in the development of plans and projects, so as to spur collaborative and integrated policies that respond to the complexity of the country’s urban-metropolitan problems.

From a historical perspective, we can say that the creation in 2003 of the Ministry of Cities and the Committee on Cities, and the national city conferences held in 2003 and 2005, were victories for the Brazilian urban reform movement, which had been working on a diagnosis for city production and management since the 1980s, and had long proposed a three-part agenda: the institutionalization of democratic city management; public regulation of urban land based on the principle of the social function of real estate property and the social function of the city; and a reversal of priorities in urban investment policy, moving toward the promotion of socio-spatial justice.

From the perspective of an urban reform agenda, the national conferences and the creation of the Committee on Cities should have created a new dynamic for urban policy management, with the participation of the government as well as popular movements, nongovernmental organizations, and the professional and business sectors. And, indeed, the policies passed since 2003 can be considered fairly significant: the National Sanitation Plan; the National Housing Plan; the creation of the National Fund for Social Interest Housing, the National Social Interest Housing System; the National Policy on Urban Mobility; and the program Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entidades. These are all examples of policies that attempt to de-commercialize Brazilian cities and promote the social function of property and the social function of the city. Although urban policy is allocated to the municipalities, this new national institutional framework contributed to a favorable climate for the adoption of progressive policies at the local level.

But the institutional advances were just one of the dimensions of the process, which was rife with discord and daily struggles. Indeed, throughout this period the enthusiasm these struggles generated was tangible: in the increased occupations of urban land and abandoned buildings; in the public demonstrations for access to sanitation services and lower public transportation costs; in the actions pressing for improvements to health services and education, and for recreation and culture options, among so many other demands; and in the urban conflicts around demands for common urban goods and greater democracy in city management.

This process–a combination of social struggles, political institutions, and philosophical reflection–gave birth to a new paradigm, or, to be more precise, the foundation of a new paradigm: the idea of the right to the city. Also known as the city-right, it involves the development of critical diagnostics to address Brazilian urban issues, along with strategy proposals for an alternative plan for cities.

However, the implementation of this new institutional framework, and of the national urban policies associated with the new paradigm of the right to the city, ran into numerous roadblocks and obstacles. These came not just from conservative sectors outside the government, as was to be expected, but also from coalitions of power within the government as they laid the groundwork for the institutional political coup of 2016 and for the conservative shift in urban politics. The beginning of this process dates to July 2005, with the replacement of minister Olívio Dutra from the Workers’ Party (PT). From that point on, the Ministry of Cities was run by representatives of the Progressive Party (Márcio Fortes de Almeida, Mário Negromonte, Aguinaldo Ribeiro, and Gilberto Occhi) and the Social Democratic Party (Gilberto Kasab)–both of whom voted to remove President Dilma and open the impeachment proceedings. When Michel Temer was installed as interim president, his Brazilian Social Democracy Party named Bruno Araújo to head the Ministry.

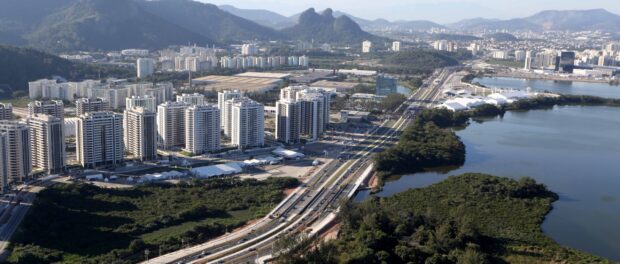

Once the conservatives took control of the Ministry of Cities in 2005, national urban policy gradually came to be marked by four major programs developed by the federal government: the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), launched in 2007, which had a significant impact on urban interventions, especially in the areas of mobility, sanitation, and housing; Minha Casa Minha Vida, launched in 2009, designed to promote the construction or acquisition of new housing units, or the rezoning of urban buildings, for families with a monthly income of up to R$5,000; the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics projects, with structural interventions related to the mega-events being held in 12 Brazilian cities and particularly in Rio de Janeiro; and the roll-out of the public-private partnership model (PPP) for urban facilities management, largely driven by the sporting mega-events which promoted this management model for use in soccer stadiums, airports, and mobility systems, as well as in the management of urban spaces linked to “urban consortium operations.”

Driven by these policies, Brazilian cities–particularly the city centers–became staging areas for major infrastructure and restructuring projects, while the tools to promote land use provided for in the City Statute encountered multiple political and bureaucratic hurdles and were rendered practically ineffective. The major urban projects implemented in Brazilian cities have not, in general, been accompanied by policies that promote and guarantee the right to the city, especially the right to housing for people living in the projects’ target areas who stand to directly suffer the negative effects. Thus in the first decade of the 21st century, alongside the general advances to the country’s national housing, sanitation, and urban mobility policies, it is important to also recognize the serious violations regarding the human right to the city; above all, in the great number of forced evictions caused by major urban projects, especially those related to the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics.

The conservative shift gained strength as these projects rolled out. The urban interventions were a clear sign of the new era of commercialization in the cities, as the most valuable land was handed over to private interests, and the poor were displaced to areas ever further from the city centers, often to areas of risk. In this new era of commercialized cities, gentrification gradually came into play as an urban renewal strategy, whereby the cities’ social, political, and economic centers were made increasingly more upscale, while working class people who had been living in these areas were simultaneously pushed out.

This process is unmistakable in the preparations for the Olympics. The city government of Rio de Janeiro appears to be directly involved in stimulating gentrification, by removing existing political and economic obstacles, making gentrification possible through market mechanisms, and by promoting the displacement of low-income communities to distant locations. In this sense, gentrification is not merely the result of real estate market forces, but constitutes a class strategy of the ruling coalition, involving a particular interaction between political power and private entities, in which policies are adopted and actions are taken that encourage gentrification in areas considered attractive to real estate capital and large-scale investors.

But conservative sectors were not satisfied with the concessions made in the name of the right to the city, and the political coup creates the conditions for the shift toward still further commercialization of cities. In the first weeks after the coup in April, the government of interim president Michel Temer announced radical policy changes, with considerable cuts to social programs, among them the cash transfer program Bolsa Família, and the suspension of Minha Casa Minha Vida-Entidades, as well as the creation of the Program for Investment Partnerships which aims to promote privatization and private-sector investment in public projects.

With the coup, the outlook now is for the broadening of the market-city paradigm in urban policy with the spread of urban entrepreneurship strategies, city marketing, and certain models of strategic planning. Urban policy gradually transforms into a series of business relationships, in which the winners are those with the most power to control the profits and costs of government initiatives. From this perspective, participants are client-consumers holding private interests, thus impeding the creation of a public sphere that would address collective interests. The city ceases to be treated as a whole, and the notion of citizenship loses its universality.

In this scenario, the progress that had been made toward the right to the city and the paradigm of the city-right, achieved through the struggle of grassroots and progressive political institutions in recent years, is at risk of being lost to the hegemony of neoliberal thinking. In the context of this conservative shift, it is worth evaluating the nature of the urban conflicts arising from current exclusionary planning, as well as the ability of progressive forces to work together to resist the coup and fight for the right to the city as a common good.

Orlando Alves dos Santos Junior is a sociologist, doctor of urban and regional planning, professor at the Institute of Research and Urban and Regional Planning (IPPUR) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), and a researcher at the Metropolitan Observatory–Millenium Institute—CNPq.