This is the latest contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

With less than three weeks to the start of the 2016 Olympic Games, Rio and its favelas are receiving more sustained media attention than ever. It’s an unprecedented opportunity to change the historically stigmatizing narrative around favelas, but also brings the risk of further consolidating tired stigmas in the minds of a global audience.

Here, we take a look at the best and worst reporting on favelas in the run-up to the Games. Next up in the series, shortly after the Games, we’ll zoom in on the best and worst produced during the Olympics.

The Worst

Unfortunately no stranger to our Worst Reporting list, the Daily Mail has outdone itself this year with its heavily stigmatizing headlines and language. Across three articles, Complexo da Maré is called a “stinking shanty town,” a “terrifying slum,” and a “dangerous no-go zone.” One article bathed in Zika hysteria quotes a health worker describing the complex as a “gigantic breeding ground” for the disease. In another article, the young boys from Maré who search through debris for recyclables are called “rat kids.” Yes, in 2016, the Daily Mail has referred to human beings as “rat kids.” A third article explains shootings, car jackings, and hostage takings on “highway of terror” Avenida Brasil as “terrifying violence” that has “spilled out from favelas.” The Daily Mail’s dedicated focus on misery and fear fundamentally misrepresents daily life for most residents of Maré. Furthermore, apparent concern for Maré residents is diminished by the line: “Most alarmingly… the shooter [on Avenida Brasil] and his powerful weapon may still be there when VIPs and sports stars start arriving for the Games”—the author has hence just made explicit his view that lives of Maré residents are not as valuable as those of Olympic “VIPs.” With some of the highest online readerships in the world, the Daily Mail must do better.

Despite a couple of favela resident perspectives that tackle the crucial discussion of who will benefit from the Olympics, this CNN video portrays Rio, and particularly its favelas, as a war zone. The video describes favelas as “the hilltop slums where heavily-armed drug gangs have long held sway,” casually ignoring the facts that most favelas are not slums, most are not on hills and most are not controlled by drug gangs. Simple, sweeping definitions like these belie the diversity found within and between each Rio favela. To interview a gang member CNN reports that “under the cover of darkness” its team “ventured into a favela” in the South Zone. Residents, tourists, and other journalists have little problem “venturing” into South Zone favelas in the daytime, so it’s unclear why CNN sought out the “cover of darkness.” Reporting their venture this way without explanation or caveat is problematic because it gives viewers a gravely exaggerated sense of the daily experience of conflict in Rio’s favelas. And the perpetuation of such stigma produces deadly policies that kill innocent residents. Maré resident and journalist Thais Cavalcante told NPR‘s On the Media last week that “this kind of coverage,” specifically mentioning sensationalist headlines, “is used to affirm certain policies of the state towards us, often justifying police brutality.”

This Gizmodo article’s attention to evictions and argument that “the poorest areas of Rio will bear the brunt” of negative Olympics impacts are valuable, but the piece contains significant inaccuracies that perpetuate myths about Olympic-driven urban development. The author writes that “many” of Rio’s hundreds of favelas now have cable cars thanks to Olympic transformations. This is simply not true—only two (controversial) cable cars currently exist in the city’s favelas, and two have actively fought against the cable cars in court. She argues Games-boosted foreign favela tourism has created “some economic stability,” but there is no evidence from Rio or past Olympics hosts that mega-events have a long-term positive effect on tourism or the economy. (Tourism has grown in favelas in recent years in the context of perceived increased security and relative economic stability, both of which have collapsed ahead of the Olympics.) The author says “Rio’s future” is dependent on tourists spending during the Olympics, but any short-term injection of cash won’t address Rio’s systemic problems. These inaccuracies both buy into and further perpetuate the City government’s narrative about the transformative potential of the Games and pre-Olympics development projects, many of which are far less impactful, and in some cases more destructive, than marketing propaganda would suggest.

A recent CityLab article merits a mention for combining a title that says the “Olympic Village Will Feed Favelas” with an article that suggests leftovers will go to “needy residents” of Lapa, which is not a favela. The article later conflates the police violence and evictions experienced in some favelas with the recipients of the soup kitchen, which risks leading readers to uncritically associate working and middle-class favelas with hunger and poverty. The Herald Sun, in its continued coverage of how Australian athletes have been banned from visiting favelas, has now informed the presumably concerned Australian public that 75% of Rio residents live in these neighborhoods, a slight increase on the actual number of around 24%. Finally, articles focused on lists of problems with the Rio Olympics often miss the opportunity to highlight issues that have taken a huge long-term toll on Rio’s communities: forced evictions, increased police violence, displacement through gentrification, misplaced spending priorities, and broken legacy promises, among others.

The Best

Lulu Garcia-Navarro’s myth-bunking article on the links between poverty and the Zika virus for NPR is an important level-headed analysis responding to the World Health Organization’s warning to visitors to “avoid visiting impoverished and overcrowded areas” during the Rio Olympics. Garcia-Navarro highlights the stigmatization in the warning and goes on to make a thorough challenge to the assertion based on scientific studies on mosquito-borne diseases and interviews with researchers in the field. The article successfully argues that visiting favelas carries no greater mosquito-related health risk than any other area of the city and concludes with a Rocinha resident’s perspective on the inaccurate, negative information promoted on favelas and the need for people to see the reality instead. Supported by relevant and broad scientific research and valuable community perspective, Garcia-Navarro’s piece is a measured and persuasive rebuttal of the WHO’s erroneous advice.

Johnny Harris’ excellent short documentary “2016 Olympics: What Rio Doesn’t Want the World to See” for Vox gives a comprehensive overview of the Rio Olympic city project and its impact on both favelas and the city as a whole. Combining impressive graphics, maps and shots across the city, Harris exposes the social cleansing project and urban remodeling underway in Rio, covering the wall erected to conceal Maré, bus route changes impeding access and real estate speculation and forced evictions in Barra da Tijuca, with a focus on Vila Autódromo. Featuring interviews with favela residents and technical specialists, the video is a powerful indictment of the Olympic city project in Rio and how the mega-event is being used to remodel the city for the benefit of temporary visitors and wealthy investors.

Ben Whitford’s article “Keeping Pace: the Rio Residents Fighting to Keep Their Communities” for Positive News is an encouraging look at the inspirational efforts, resistance activities and constructive, creative movements in Rio today. In direct contrast to the disempowering, sensationalist portrayal of favelas as violent, poverty-stricken and squalid, Whitford emphasizes the community pride that has fueled Vila Autódromo’s resistance campaign, creative organizing in the city and grassroots solutions. The increased activism, civic engagement, community journalism and growth of resistance networks in Rio in recent years are important developments that are little reported and often neglected in favor of inaccurate and actively harmful favela narratives. By focusing on the positive swell of empowered, connected and creative movements in Rio, Whitford’s article disputes the stigmatizing view of favelas as passive places of lack, violence and need and documents the vibrant, dynamic and empowered movements looking to shape the city.

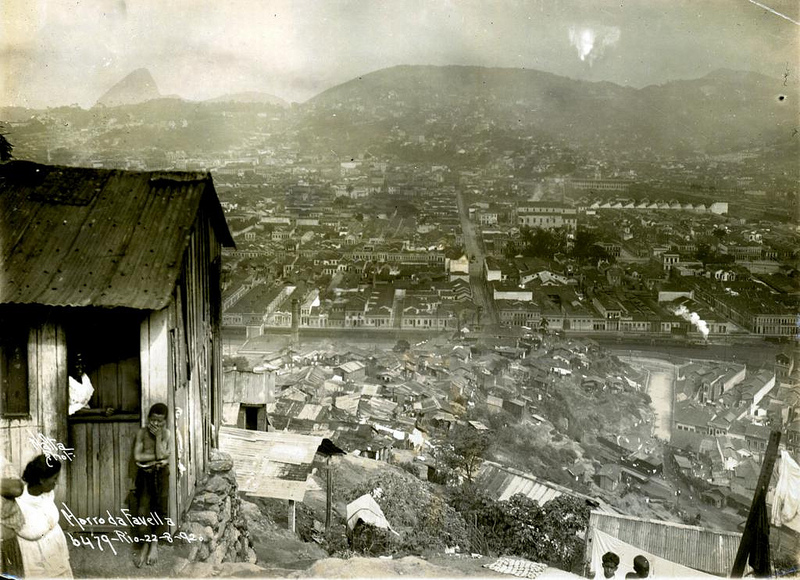

Published as part of The Guardian’s Story of Cities series, Bruce Douglas’ history of Providência is a fascinating dive into the first favela’s past and current situation. The article is unfortunately and misleadingly titled “the rise and ruin of Rio de Janeiro’s first favela”–no rise and fall is charted, instead Douglas recounts Providência’s beginnings and, importantly, prevailing early 20th stigmas before examining the present-day challenges based on resident interviews. Evidence of historical stigmas towards the favela provides valuable context: the police report from 1900 which bemoaned the impossibility of policing the area, the 1904 cartoon showing favela residents being combed out of Rio’s head, and French urban planner Alfred Agache’s design plan to remove Providência set the stage for the recent, non-participatory interventions, such as the cable car, outlined and challenged by residents in the second part of the article. With thorough research and resident stories, the article provides a meaningful look at Providência’s history and some of the prejudices and perceptions which have shaped it.

Finally, NPR’s ‘On the Media’ show produced a must-listen piece for all journalists reporting on Rio about the challenges of reporting on favelas in national and international media. Due to the emphasis on violence in favelas on TV and in dramatic headlines, Maré journalist Thaís Cavalcante says: “Before I was part of this newspaper, I would lie to other people and say that I didn’t live in Maré. I was ashamed of living in a favela.” This sense of personal shame, combined with media’s power to influence perceptions and justify damaging policies, are evidence that story-telling brings the risk of further marginalizing already historically marginalized communities. At the same time, On the Media’s program suggests that journalism that challenges dominant narratives or that empowers activists like Vila Autódromo’s Maria da Penha, also featured on the show, can be transformative. The piece also highlights the resources available on RioOnWatch to support journalists in producing nuanced reporting.

The good news is there is much informed, nuanced and fantastic reporting on Rio and the favelas happening in the lead up to the Olympics, too much to be featured here! Special mention goes to The Guardian’s ongoing series, the View from the Favelas, which is giving community journalists including Thaís Cavalcante from Maré, Daiene Mendes from Complexo do Alemão, and Michel Silva from Rocinha an international platform to voice their views and tell the stories from their communities. Tech Insider’s short report on Rocinha having its own WiFi provider is a stigma-busting look at favelas as valuable neighborhoods with their own business communities and tech infrastructure. Finally, Jules Boykoff, author of Power Games: A Political History of the Olympic Games, provides insightful, detailed and in-depth analysis of the Rio Olympics on Folha de São Paulo’s From Brazil blog.