In Estácio, a centrally located neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, Block 15 of the Zé Keti social housing complex, part of the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) program, has been the home of some of the city’s remaining indigenous families since June 2013. Its residents have described the complex, built on the grounds of the former Frei Caneca prison, as being too restricted and “full of rules.”

After being forcibly removed from their occupation at the old Indigenous Museum next to the Maracanã stadium, these 17 indigenous families were initially placed in containers in Curupaiti, in Jacarepaguá, over one hour away in the West Zone. They stayed there for about a year before they were moved once more to the MCMV apartments. “[The mayor] promised to build us a typical village in 18 months. He didn’t succeed… This MCMV program was the only alternative he offered,” says Carlos Doethyró Tukano, president of the Aldeia Maracanã Indigenous Assembly (AIAM).

After two years living in Estácio, the list of complaints about the social housing complex is still growing. Among them, leaks and water loss, cracks in floor tiles, decomposition of wall’s infrastructure, and high accumulated bills–residents of Block 15 have to pay monthly rent as well as gas and electricity, which are not included in the contract. Their biggest complaint to date, however, is lack of space.

Brazil’s indigenous people are accustomed to receiving large groups of people, whether it be for reunions, rituals, festivities, or other opportunities to express their culture. This has become nearly impossible in the MCMV complex, where doors are often kept closed and there is no common area that can be used for such traditions. “It’s not that it’s bad. For those who like it, it’s good. But for those who like to have some freedom… it is very delicate. We can’t receive many people here.” Tukano also pointed out that they would not have the same opportunities to exhibit their culture during the Olympics as they would have had in the Aldeia Maracanã. Many people are not even aware they have been relocated here.

According to Law 6.001 on the Statute of the Indigenous, the government should “secure for indigenous people the possibility of free choice of their means of living and subsistence” (Title I, Art. 2, IV) and “execute whenever possible according to the indigenous collaboration, the programs and projects meant to benefit indigenous communities” (Title I, Art. 2, VII). The indigenous community of Aldeia Maracanã has been attempting to procure a new space where they will be able to receive people, including other indigenous communities passing through Rio. They lament that they will not be able to do so during the Olympic Games, during which many indigenous communities will be visiting the city. Carlos Tukano reiterated his wish that the City soon fulfill their promise of restoring a building to allow them to fully practice their culture once again.

Besides being restricted in space and cultural practice, some of the indigenous residents of the Zé Keti complex have also restricted their own attitudes within the neighborhood. “Here no one knows who’s who,” says Carlos Tukano, who tells his daughters to be careful what they say and how they act in the neighborhood. He continues: “Indigenous people are already badly perceived, mixing up with these things will bring even more problems,” referring to the militia and drug gangs trying to control the neighborhood. Within the complex itself, the indigenous community does not really mix with other residents either. The various tribes living in the building all know each other, but this is not true of all the buildings in the complex, Tukano says.

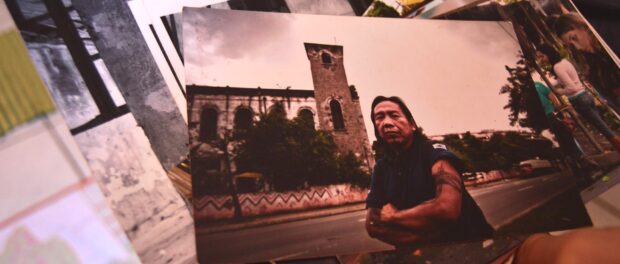

The community will keep looking for a new space until they can practice their culture in serenity once more. Some families will stay, but Carlos Tukano is determined to move. He will not give up on the fight for culture that he began 27 years ago, when he left his home in the Amazon to discover urban life in Rio de Janeiro.